Canadian women at average breast cancer risk should undergo biennial or triennial screening and make decisions based on individual values, according to new guidelines set by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC).

The task force on May 30 released its updated guidance on breast cancer screening, which recommends that women between the ages of 40 to 49 not be systematically screened for the disease with mammography but rather make their screening decisions based on informed discussions with their primary care provider. The guidelines differ slightly from the the recent U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) breast cancer screening guidelines, which recommended biennial screening, and do not support supplemental screening in women with dense breasts or with a family history of breast cancer.

“The risk-benefit in this category does not align with patient preferences and values, but we feel it’s very important that once that information is received, if people want access, it should be there,” said Kate Miller, MD, from McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. Miller is a member of the task force.

In February 2023, the CTFPHC decided that the 2018 guidelines needed updating. The group consists of six family physicians, four specialists, and two nurse practitioners; this recommendation update also involved a working group of a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, a surgical oncologist, a radiologist, and three patient partners. CTFPHC reviewed evidence from literature searches, systematic reviews, other data, and modeling and placed them into a decision framework.

For women ages 40 to 49, the group reported that “the majority” may weigh screening harms as being greater than the benefits. Miller noted that there is variability in patient values and preferences, as well as a lack of data from racially and ethnically diverse populations.

The research used to update the guidance suggested that women at age 40 do not experience a significant decrease in breast cancer mortality compared with women at age 50. Additionally, it suggested that younger women may be more at risk of undergoing unnecessary additional testing, such as biopsy.

The updated guidelines recommend that women between 50 and 74 undergo screening every two to three years. Miller said that a “large majority” of these women believe the benefits of screening outweigh the harms. However, she added that individual values should also be considered for these women.

In addition, the guidelines also recommend that women ages 75 and older at average risk should not undergo screening, citing no significant benefits. The guideline updates do not apply to women deemed to be at high risk for developing breast cancer, the task force noted.

“Breast cancer [screening] is a personal choice, and people deserve information so they can make the right choice for them,” Miller said. “We believe that a one-size-fits-all approach is not appropriate for Canadian women particularly given our knowledge of the benefits and harms, and values and preferences.”

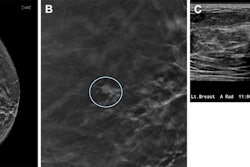

The recommendation also suggests not to use MRI or ultrasound as supplementary screening tests for women with dense breasts (category C or D) and for women with a personal family history of breast cancer. Miller said the task force did not find significant evidence of the benefits of supplemental screening on patient outcomes such as stage of diagnosis or death for these women.

Guylène Thériault, MD, co-chair of the task force, said the main message of the updated recommendation is that it is important to know the benefits and harms of breast cancer screening and that there “needs to be a discussion for women to make a decision based on their values and benefits.”

“In my practice, I use shared decision-making tools. I see women deciding to be screened and women deciding not to,” she said. “We must ensure these choices are informed with the best quality evidence and respect each individual’s choice. I would not see myself practicing any other way.”

Finally, the CTFPHC said it has joined groups such as the USPSTF in calling for more research and data on the impact of screening on Black women and other racially and ethnically diverse populations, and on supplemental screening for women with dense breasts or a personal family history.

Thériault added that the task force will provide tools on its website in the coming months for everyone to use, including for women to get connected with primary care physicians. Additionally, there will be a six-week period for stakeholder and public comments.