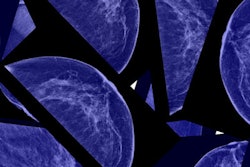

Black women have a higher risk of dying from breast cancer across all tumor subtypes compared with their white counterparts, according to research published September 17 in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

A team led by Juliana Torres from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center in Boston, MA, found that the size of this disparity varied from 17% to 50% depending on the type of breast cancer.

“Data consistently show that Black women have mammography screening rates that are the same or better than white women in the U.S.,” corresponding author Erica Warner, ScD, from Massachusetts General Hospital told AuntMinnie.com. “So, this suggests that to improve early detection, we need to make sure that women with abnormal findings receive timely diagnostic care and treatment [if needed].”

Black women who develop breast cancer are about 40% more likely to die of the disease compared to white women, despite advancements in early detection and treatment. The researchers however noted that little is known about how this disparity translates to various types of breast cancer.

Torres and colleagues performed a meta-analysis to determine the extent of disparities in breast cancer survival between Black and white women according to tumor subtype.

The group's analysis included data from 18 studies published between 2000 and 2022 for 228,885 women. Of these, 182,466 were white and 34,262 were Black. The team observed that compared with white women, Black women had a higher risk of breast cancer death for all tumor subtypes.

The researchers found the following regarding summary risk of breast cancer death among Black women:

- The risk was 50% higher among hormone receptor-positive and HER2-negative tumors (relative risk [RR], 1.5, with 1 as reference).

- The risk was 34% higher for hormone receptor-positive/HER2-negative tumors (RR, 1.34).

- The risk was 20% higher for hormone receptor-negative/HER2-positive tumors (RR, 1.29).

- The risk was 17% higher among individuals with hormone receptor-negative/HER2-negative tumors (hazard ratio, 1.17).

Also, Black women had poorer overall survival than white women for all tumor subtypes.

The study authors wrote that this disparity is exacerbated by structural racism, defined as a system that unfairly dictates opportunity, access to resources, and interactions with institutions and individuals across the cancer care continuum according to socially defined racial categories.

“Structural racism through the laws, policies, and practices that codify it, such as redlining, has led to widespread socioeconomic inequality with lower individual- and area-level socioeconomic status among Black populations compared with white populations in the U.S.,” they added.

The team also wrote that Black patients are more likely to receive care in facilities with lower-quality ratings, which may lead to poor-quality mammograms, delays in diagnosis, and less access to treatment.

Warner added that it’s important that healthcare systems track how they are doing regarding the care of women with breast cancer and interrogate their data by demographic factors like race to see where they may be underperforming and intervene.

“We need more diversity in clinical trials to ensure that Black women and other underserved populations get access to new therapeutics and also that the medications and interventions we design are effective for them,” she said.

Warner told AuntMinnie.com that the team has been working on a six-week education and support intervention for Black women with breast cancer (thrivebreastcancer.org). The goal of the effort is to ensure that Black women have what they need not just to survive but also to thrive after breast cancer. This includes talking to their physicians, receiving follow-up care, and surveillance for recurrence, and managing post-treatment symptoms.

“We plan to test this in a larger study in the next year,” Warner said.

The full results can be found here.