About two in every five women in their 40s do not receive their biennial breast cancer screening per U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations, according to findings published December 20 in JAMA Network Open.

A team led by Minghui Li, PhD, from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis also found that these numbers are more disproportionate in women of racial and ethnic minority populations, sexual minority populations, rural residents, and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations.

“To optimize early breast cancer detection, ensuring equitable adherence to USPSTF recommendations is crucial,” Li and colleagues wrote.

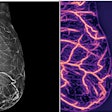

The USPSTF in 2024 released its updated recommendations for breast cancer screening. The recommendations state that women ages 40 to 74 years should receive biennial mammography screening, a B-grade recommendation. This succeeds the previous recommendation, which said that women in their 40s should make informed individual decisions about screening.

Some goals from this change include advancing early breast cancer detection and addressing inequities in breast cancer mortality.

Li and co-authors explored disparities and gaps in breast cancer screening among women in their 40s. They used data from the National Health Interview Survey in 2019 and 2021, which included women aged 40 to 49 years who had not previously been diagnosed with breast cancer.

Among the 20.1 million women included in the study, 11.7 million reported having undergone mammography screening within the last two years. Also, 3 million reported being screened more than two years ago, and 5 million reported never undergoing mammography screening.

The researchers also found that biennial screening rates were significantly lower among the following groups: non-Hispanic women of other races, lesbian and bisexual women, rural residents, and women with a family income at 138% or less of the federal poverty level.

“The rate of biennial screening decreased as family income decreased,” the team added.

Also, not having a usual place of care was significantly tied to higher odds of overdue screening (risk difference [RD], 0.07), compared with biennial mammography screening.

Finally, the following factors showed associations with higher odds of no screening:

- Being non-Hispanic Asian (RD, 0.09)

- Family income based on federal poverty line (RD, 0.07)

- Being uninsured (RD, 0.13)

- Lacking a usual place for care (RD, 0.2)

“The absence of a usual place for care was associated with both overdue and no mammography screening,” the researchers wrote.

The study authors called for efforts to focus on addressing delays and making sure treatment goes by standard guidelines to reduce racial disparities in breast cancer mortality. They added that emphasis should be placed on addressing the needs of women who do not have a usual place for care.

“Targeted interventions and policies aimed at enhancing health care access, coverage, and affordability hold significant potential to improve health equity in biennial mammography screening for women aged 40 to 49 years,” the authors wrote.

The full study can be found here.