If you think artificial intelligence could replace radiologists someday, there may be a new menace: It turns out that pigeons can distinguish benign from malignant tissue and identify certain cancer features with similar accuracy as their human counterparts, according to a new study published in PLOS One.

How great a threat to radiology are the birds we call Columba livia? Well, that depends, according to lead author Dr. Richard Levenson from the University of California, Davis.

"We know much less than we should about human visual capability," Levenson told AuntMinnie.com. "And just like studies that use artificial intelligence, animal research is another way to explore important questions related to how vision is used in medical situations. But don't worry -- the human still has to make the final call."

Dr. Richard Levenson from the University of California, Davis.

Dr. Richard Levenson from the University of California, Davis.Room for improvement

Radiologists spend years developing and improving their visual skills. Yet there's considerable room for improvement in image perception and interpretation, not only through visual and verbal training, but also through image acquisition technology, image processing, and display.

These measures must be validated for quality and reliability, and that can only happen with trained observers -- a necessary but time-consuming and expensive process. For all the promise of artificial intelligence, automated, computer-aided substitutes often fail to accurately reflect human performance, according to Levenson and colleagues.

Because pigeons share many visual-system properties with humans, the animals seemed a natural fit for research that would explore how pathologists and radiologists acquire and refine the visual skills necessary for their work (PLOS One, November 18, 2015).

"Given the well-documented visual skills of pigeons, it seemed to us possible that they might also be trained to accurately distinguish medical images of clinical significance," the authors wrote. "The basic similarities between vision-system properties of humans and pigeons also suggested that, if pigeons were confronted with pathology and radiology study sets of increasing difficulty, then their task accuracy would track that achievable by ... human observers."

Birds of a feather?

The study addressed four questions:

- Could pigeons be taught to discriminate between benign and malignant features on pathology and radiology images?

- Could they go beyond memorization and perform accurately with new images?

- How would they perform when given image discrimination tasks that are difficult even for skilled human observers?

- If the birds were successful, could their skills have any practical use?

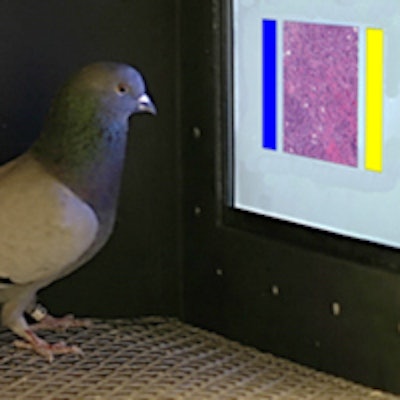

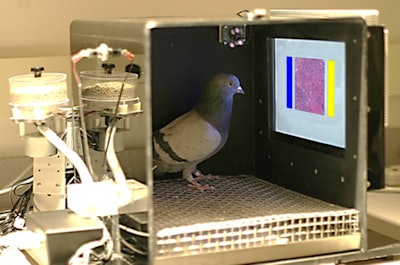

Unlike many animals, pigeons can see color, so Levenson's team used food rewards and two response buttons of different colors to test the birds' ability to identify benign or malignant breast pathology specimens. Magnification levels of breast pathology slides were low (4x magnification), medium (10x), and high (20x). The birds were then tested on their ability to identify microcalcifications and masses.

The birds were trained in "operant conditioning chambers" -- essentially bird reading boxes that were placed in a dark room. Each box had a 15-inch LCD monitor behind a touchscreen; a dispenser delivered food pellets through a tube into a cup placed on the opposite side of the box.

And you thought your reading room was small. Image courtesy of Edward Wasserman, PhD, University of Iowa.

And you thought your reading room was small. Image courtesy of Edward Wasserman, PhD, University of Iowa.Levenson and colleagues used 144 images taken from breast tissue samples from routine pathology cases and mammography exams. The images were divided into groups of 48 for the three magnification settings; each group included equal numbers of benign and malignant samples.

The team basically conducted three experiments: one to test the pigeons' ability to determine breast tissue histopathology, another to identify microcalcifications, and a third to identify masses. For each experiment, the pigeons underwent a two-week training period to acclimate to the particular type of images, followed by a test period during which they were exposed to both familiar and new images.

Histopathology

The birds' ability to discriminate between benign and malignant breast tissue pathology samples over the three levels of magnification increased from 50% at the outset of the experiment to 85% over 15 days of training, a statistically significant change. Furthermore, the researchers found that the birds could do this when exposed to new samples: Their accuracy averaged 87% on familiar images and 85% on new ones (although this result was not statistically significant).

When the researchers modified the images in terms of color, brightness, and compression artifacts, the birds' ability to identify tissue samples remained, even when they were shown monochrome, hue-normalized benign and malignant images at 10x magnification. Their accuracy did break down, however, when they were shown new monochrome images as compared with new full-color images.

Microcalcifications

The birds were just as able to classify mammography images with and without microcalcifications, with their accuracy increasing from 50% at the beginning of the experiment to 85% over 14 days of training.

"The problem of finding little white specks in a complex background would seem to mirror the problem encountered in the pigeons' native environment, of locating and ingesting seeds ... an obvious survival skill," Levenson and colleagues wrote.

When the birds were shown additional new images with and without microcalcifications after this initial training period, their accuracy rate averaged 84% for familiar and 72% for new images; the researchers showed these same images to radiologists and radiology residents, who averaged 97% accuracy for the images without calcifications and 70% for those with calcifications.

"In fairness, unlike the pigeons, the radiologists were not shown just small regions of interest, but whole images that had to be searched for abnormalities, a more challenging task," Levenson and colleagues conceded.

Masses

The pigeons found identifying masses on mammography to be a much harder task, and the training period was longer (almost 12 weeks instead of two weeks). Average accuracy scores during the testing period were 74% for familiar images and 44% for new ones.

"Correctly identifying these challenging target masses is difficult even for trained radiologists; and in fact, it proved to lie at the limits of the pigeons' capabilities," the group wrote.

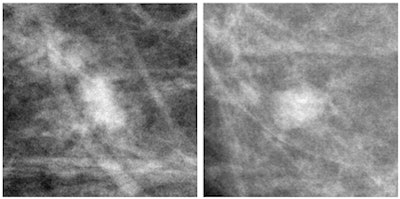

Above, example of malignant (left) and benign (right) mass images shown to pigeons. Below, example of calcification (left) and no-calcification (right) images shown.

Above, example of malignant (left) and benign (right) mass images shown to pigeons. Below, example of calcification (left) and no-calcification (right) images shown.A bird in hand ...

The group isn't advocating that pigeons be installed in radiology reading rooms to offer clinical diagnostic support, said co-author Elizabeth Krupinski, PhD, of Emory University. But the study does suggest another purpose for this kind of research.

"As radiologists' workloads increase, they have less time to participate in research," she told AuntMinnie.com. "So we could use animal subjects to set preliminary parameters on future human studies, for example, to investigate how much a digital breast tomosynthesis image can be compressed and still retain its diagnostic accuracy. Narrowing the compression range with pigeons would allow for a more tailored experiment with radiologists, which would save time."

Future studies with pigeons could also help researchers determine why the animals see what they see -- and translate this information into radiologist training and education, Levenson said.

"One practical application of this research would be using it to structure training materials -- working with the pigeons first and then tailoring the information for people," he said. "And if we could understand why some pigeons saw the microcalcifications and some didn't, or why they often missed masses, perhaps we could understand what makes a good radiologist as well."