By William N. Bernstein, ACHA, AIA

Bernstein & Associates, Architects

Here’s the situation: in healthcare architecture, an architect needs detailed equipment specifications for the major pieces of fixed equipment (starting with the manufacturer name and model number), in order to design the facility properly. To accomplish this, the client gives the architect a list of equipment manufacturers and model numbers at the beginning of the design process.

But here’s the problem: clients sometimes change their minds about equipment specifications (for example, the manufacturer, or model number). Sometimes the change occurs during the architectural design process. In some cases, the specifications change occurs after the construction documents are complete. And in the worst case, the specification change occurs during construction, or even after construction is complete.

Are equipment specification changes a big deal? It depends.

In some cases, the specification change is made with little effect on the design or construction. But that’s probably the exception. Most of the time, a specification change has a major impact on the project.

The scope of the change can grow depending on the size of the equipment and the point at which the change is made in the process. As an example, a change made to a mobile ultrasound machine at any point during the process has a minimal effect. On the other hand, a specification change made to a 1.5-tesla MR system after construction is complete could have an enormous impact.

Here's the moral of the story: If you want to control costs, don’t change your mind about the equipment. Or if you do change your mind, try to do so early on in the process, and confine the change to the smaller, less significant equipment.

If you must make a change regarding the larger equipment, try to do so as early as possible during the design process. Small and early is good, big and late is bad.

Is there a way that clients can protect themselves against project cost increases resulting from equipment changes (other than avoiding equipment changes)? Yes, in part: the design of what is called a "universal room" can mitigate to some degree the costs (both financial and in terms of schedule delay) of equipment changes.

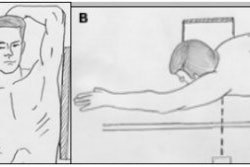

A universal room is a room designed to allow -- on a certain level -- any number of equipment options within a certain, predetermined range. As a quick and simple example, let’s say you’re planning a 1.5-tesla MRI room, and are not sure which manufacturer/model number you’ll be selecting.

A typical ("non-universal") design process assumes one manufacturer/model number, with resultant problems if the manufacturer or model number is changed later on. A universal room, on the other hand, is planned following review of a limited number of manufacturers/model numbers (say, the largest 1.5-tesla MRI from GE Medical Systems, Siemens Medical Solutions, and Philips Medical Systems).

In developing the universal room, the architect looks at each of the manufacturers’ systems, and takes the worst case of a number of parameters from the manufacturers’ equipment specifications. For example, the worst-case parameters may be the largest room required, the heaviest equipment, the highest number of BTUs emitted, and the largest electrical requirement. With all these factors in hand, the architect designs a universal room that takes into account a "perfect storm" of worst-case parameters.

So then, is the design of a universal room a no-brainer, recommended in every instance of a major equipment purchase? Not exactly.

First of all, by nature a universal room is over-designed. A universal room is probably bigger that it may need to be, has more structural support than it may need, more cooling than it may need, and more electrical power than it may need. The key terms here are "added space" and "added cost."

Also of note, you are not eliminating required decisions -- you are only deferring them. A design for an MRI room, for example, can only proceed so far without a final selection of equipment by manufacturer and model number.

While not a panacea, design of a universal room may have relevance for your next imaging construction project. This relevance may increase (or decrease) depending on several factors discussed above, including size of equipment; certainty and timing of decision on equipment manufacturer and model number; available space; and available mechanical and electrical infrastructure services.

By William N. Bernstein

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

May 16, 2003

William N. Bernstein is principal of two architecture and interior design firms in New York City: Bernstein & Associates, Architects (www.bernarch.com) specializing in healthcare, laboratories, and office space; and Architecture for Radiology, LLP (www.arch4rad.com) specializing exclusively in radiology facilities. He is a Yale University-trained architect with more than 20 years experience in the design and construction of specialized, technically demanding facilities in the U.S. and Canada. Bernstein is a member of the American College of Healthcare Architects and the American Institute of Architects, and can be contacted at 212-463-8200 or at [email protected].

Related Reading

Ten points of the new healthcare architectural design, February 10, 2003

Facility-planning implications of the new MRI safety guidelines, September 9, 2002

MRI design resonates with functional, aesthetic qualities, July 22, 2002

Finding the right space for a new imaging center, July 15, 2002

The Architecture of Imaging, January 31, 2002

Copyright © 2003 William N. Bernstein, ACHA, AIA