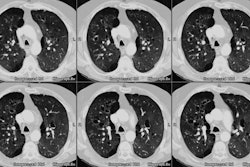

Atelectasis/Collapse:

View cases of atelectasis

Types of Atelectasis:

1. Obstructive Atelectasis:

Obstructive atelectasis is also referred to resorption atelectasis. Blood circulating through the capillary bed of the obstructed portion of lung begins to resorb air from it. In otherwise healthy lung, complete resorption of air will take place within 24 hours after acute bronchial obstruction. In patients receiving 100% oxygen, complete atelectasis of an obstructed lobe can occur within an hour after acute bronchial obstruction due to the increased oxygen gradient. In cases in which bronchial obstruction develops slowly (such as in the setting of bronchogenic carcinoma) obstructive pneumonitis is often found distal to the obstructing lesion. In cases of peripheral airway obstruction, the larger airways remain patent and are filled with air. This accounts for the presence of air bronchograms within atelectatic lung. The rapid accumulation of secretions within the larger airways will result in disappearance of these air bronchograms in many cases, although the branching mucous filled bronchi can be very evident on contrast enhanced CT scan. In some circumstances, rather than losing a significant amount of volume, the affected portion of lung will predominantly fill with fluid. This condition is termed "drown lung." Generally, collapsed lung enhances to a greater degree than tumor and on post-contrast studies, tumor typically appears as a poorly marginated low attenuation area compared to the more uniform enhancing atelectatic lung. This difference in enhancement is felt to be related to increased blood flow per unit area of collapsed lung compared to tumor [1]. The obstruction of a large bronchus does not always result in atelectasis as collateral air drift readily occurs between segments within a lobe and can also occur between contiguous lobes separated by an incomplete fissure.

Although atelectasis is not a common manifestation of pneumonia in adults, endobronchial and peribronchial inflammation from bronchopneumonia can result in small airway obstruction followed by atelectasis (referred to as 'atelectatic pneumonia').

The "double lesion" sign was described by Felson- he noticed that as the anatomic separation between two collapsed lobes increases, the likelihood of bronchogenic carcinoma as the cause of the combined collapse decreases. For example, many cases of combined RML and RLL atelectasis are due to bronchogenic carcinoma, however, combine atelectasis of the RUL and RLL (with sparing of the RML) is difficult to explain on the basis of a single bronchial lesion.

2. Adhesive Atelectasis:

Adhesive atelectasis stems from surfactant deficiency. Once collapsed, the alveolar walls tend to adhere, making re-expansion difficult. A number of conditions have been shown to produce adhesive atelectasis due to surfactant deficiency including hyaline membrane disease, ARDS, smoke inhalation, cardiac by-pass surgery, uremia, prolonged shallow breathing, and pulmonary embolism. In pulmonary embolism focal ischemia distal to the embolus can result in a marked reduction in surfactant levels leading to sub-segmental or even segmental atelectasis.

3. Passive Atelectasis:

The presence of a pneumothorax can result in passive atelectasis of the adjacent lung.

4. Compressive Atelectasis:

Any space occupying lesion in the thorax (pleural effusion, empyema, pleural tumors, and large bullae) can compress the adjacent lung.

5. Cicatrization Atelectasis:

This condition denotes volume loss stemming from decreased pulmonary compliance due to localized or diffuse pulmonary fibrosis. There is usually associated bronchiectasis.

6. Rounded Atelectasis:

Rounded atelectasis represents folded atelectatic lung with fibrous bands and adhesions to the visceral pleura. There is a high incidence in asbestos workers (65-70% of cases, most likely due to high degree of pleural disease). Affected patients are typically asymptomatic and the mean age at presentation is 60 years. It is seen most commonly posteriorly in the lung bases (90%), especially in the paraspinal gutter. Over time, most lesions remain stable in size, but enlargement or regression have been described. Three criteria are necessary for the diagnosis of rounded atelectasis: 1- A focal mass-like lesion abutting a region of thickened pleura; 2- Associated volume loss in the involved lobe; and 3- Bronchovascular structures radiate from the lesion in a "comet tail" fashion towards the hilum.

CXR demonstrates a crescentic/elliptical soft tissue mass abutting the pleural surface associated with evidence of pleural disease (thickening or calcification). The mass typically forms an acute angle with the pleural confirming it's intrapulmonary location. On CT the pleural thickening or calcification is clearly identified. Thickened lung markings and vessels swirl into the lesion which abuts the pleural surface ("comet tail sign"- central bronchovascular pedicle). Curvilinear air bronchograms are often visible within rounded atelectasis. The lesion may be based or tethered by a strand to a thickened pleural surface. Pericicatril emphysema may also be seen. Volume loss within the affected lung is also common. The lesion will enhance homogeneously after the administration of I.V. contrast. On MRI, rounded atelectasis has a higher signal intensity than adjacent pleura on T1 images, and the folded visceral pleura may sometimes be identified as a curved, low-signal line within the atelectatic lung tissue. [2]

7. Generalized Atelectasis:

This term is used to describe widespread volume loss, however, opacification of the lungs may be mild or inapparent, and high positioning of the diaphragm may be the only clue to the presence of volume loss. Due to the absence of opacification, most cases of generalized atelectasis are often misinterpreted as a poor inspiratory effort. Conversely, when generalized atelectasis is associated with diffuse pulmonary opacification, most cases are indistinguishable from diffuse pulmonary edema. High positioning of the diaphragm is the clue to the correct diagnosis. Generalized atelectasis can be associated with marked arteriovenous shunting.

X-ray:

Radiographic findings which suggest atlectasis can be divided into direct and indirect signs:

Direct signs of volume loss include shift of a fissure, crowding of the vascular markings, and crowded air bronchograms.

Indirect signs include shift of the hilum (best indirect indicator of collapse), pulmonary opacification, tracheal (or cardiac/mediastinal) shift, hemidiaphragm elevation, compensatory hyperexpansion of the surrounding lung, approximation of the ribs, and shifting granulomas. The degree of opacification does not necessarily indicate the severity of collapse. Residual non-atelectatic lung which contains fluid, rather than air, will appear more dense on the radiograph. Air bronchograms are typically absent in atelectatic lung, however, they may be seen, especially on CT scanning.

Atelectasis of Individual Lobes:

Right upper lobe collapse: On the PA view there is superior displacement of the minor fissure and right hilum. The collapsing lobe produces opacification adjacent to the upper mediastinal border and the right upper lobe pulmonary artery and vein disappear. A peak-like shadow along the medial aspect of the right hemidiaphragm is evident in some cases and is referred to as a "juxta-phrenic peak." This finding is more common in left upper lobe collapse, however. The formation of the peak is thought to be related to traction on the basal pleura by the inferior pulmonary ligament. It has also been ascribed to upward retraction of the inferior accessory fissure or an intrapulmonary septum associated with the pulmonary ligament [9]. In severe cases the RUL becomes pancaked against the lung apex or upper mediastinum and can be mistaken for apical pleural thickening. On the lateral view, the collapsing RUL assumes a triangular shape with the apex at the hilus and the base at the thoracic apex which has been referred to as the "mediastinal wedge." Segmental atelectasis of the right upper lobe can also be seen. Collpase of the apical segment produces an opacity against the thoracic apex. Anterior segment collapse produces an opacity that projects over the hilus on the PA view, while producing a triangular opacity on the lateral exam with its apex at the hilum and the base directed at the anterior chest wall. Posterior segment collapse appears similar to anterior segment collapse on the PA exam, but produces a wedge shaped opacity on the lateral with it's base against the superior portion of the right major fissure (that may be displaced anteriorly). On CT, the collapsed RUL appears as a wedge-shaped soft tissue opacity along the upper right mediastinal border which extends to the anterior chest wall.

The 'Golden "S" sign' occurs when there is a characteristic downward bulge in the medial portion of the superiorly displaced minor fissure (near the hilus) in cases of RUL collapse which produces a reverse "S" appearance to the shape of the minor fissure. This sign is highly suggestive of bronchogenic carcinoma as the cause of RUL atelectasis, but the concept can be applied to collapse of any lobe.

The 'Luftsichel sign' occurs when the hyperexpanding superior segment of the RLL or the RML becomes insinuated between the mediastinum and the collapsing RUL (this finding is more common in LUL collapse). On the PA view, the hyperexpanded lung forms a lucency between the mediastinum and the opacity of the collapsed RUL.

Combined RUL and RML atelectasis resemble atelectasis of the LUL. Combined right upper and right middle lobe atelectasis secondary to malignancy is not as uncommon as would be presumed. Anatomically, the bronchi to these respective lobes are only about 3.5 cm apart. Additionally, a group of lymph nodes known as "Borrie's lymphatic sump," are situated between the two bronchi and receive lymphatic drainage from all three right lung lobes [3]. On the PA exam it appears as a homogeneous opacity in the right hilum which obscures the right heart border, ascending aorta, and right side of the mediastinum.

Right middle lobe: RML collapse will best be identified on the lateral exam where it forms a wedge shaped density over the cardiac shadow. On the PA exam, RML collapse produces a triangular shaped opacity with it's apex against the chest wall, and it's base against the right heart border (which will be obscured [silhouetted] by the opacity). This appearance is very evident on an apical lordotic exam. Because of the small volume of the RML, mediastinal shift, hilar displacement, and obvious hyperexpansion of the RUL and RLL lobes are usually absent. Segmental collapse of the medial segment of the RML is the more common form of segmental collapse. It resembles collapse of the entire RML except that the minor fissure remains visible as a thin line outlined by the aerated RUL (above) and lateral segment of the RML (below). On the PA view, segmental collapse of the lateral segment of the RML produces an opacity which abuts the inferior aspect of the right minor fissure. Since the medial segment remains aerated, the right heart border is not obscured.

Right lower lobe: The collapsed RLL will obscure the right hemidiaphragm, the right paraspinal interface, and the inferior vena cava. The right heart border remains visible since it is outlined by aerated RML. The right minor fissure is inferiorly displaced. With increasing severity of RLL collapse, a greater length of the right hemidiaphragm will become visible. At the end-stage of collapse, the RLL becomes pancaked against the paraspinal area- forming a triangular opacity behind the right side of the heart on the PA view. Dr. Pronto feels that right lower lobe collapse characteristically produces a "small hila sign." The normal vascular structures are not identified in this situation because they are obscured by the collapsed lung. Marked elevation of the right hemidiaphragm may occur in response to RLL collapse and in these instances the hilus will be only mildly depressed. In such cases, the opacity produced by the RLL may be only minimal.

The "upper triangle sign" refers to the rightward shift of the anterior mediastinal triangle and anterior junction line in cases of RLL collapse. The "Gatling gun" sign occurs when air bronchograms clustered in the RLL are seen end-on below the right hilus.

Combined RML and RLL collapse will produce a triangular shaped density which obscures the right hemidiaphragm and right heart border. Other findings include a small and depressed right hila, and decreased vascularity in the right lung compared to the left side. Severe combined collapse may be difficult to identify as the collapsed lung pancakes medially against the heart- preserving the appearance of the hemidiaphragm laterally. Another finding which may help in such cases is apparent bronchoarterial inversion of the vessels to the right lower lung. Normally, the interlobar pulmonary artery lies along the lateral aspect of the bronchus intermedius, while the RUL artery is located along the medial aspect of the corresponding bronchus. With combined RML and RLL collapse, the RUL expands to fill the right hemithorax. The arterial-bronchial relationship of the RUL is not affected, and therefore, the displaced right upper lobe pulmonary artery which appears to be supplying the right lower lung will lie medial to the corresponding bronchus- an inversion of the normally anticipated relationship. [4]

Left upper lobe: Normally, the left upper lobe is bounded posteriorly by the major fissure which runs obliquely from the anterior aspect of the left hemidiaphragm to the level of T5 posteriorly. As the left upper lobe collapses, it moves anteriorly and superiorly to lie against the anterior chest wall. On the PA exam, the opacity produced by the collapsed LUL obscures the left upper mediastinal border, the aortic arch, and a segment of the left heart border. Typically the lateral edge of this opacity is ill-defined. The hyperexpanding superior segment of the LLL often rises above the collapsed LUL and frequently it becomes insinuated between the upper mediastinum and the opacity produced by the collapsed LUL- this is refered to as the "Luftsichel sign" (para-aortic crescent of hyperlucency) [7]. In such cases, the aortic arch becomes visible on the PA exam and the collapsed LUL may mimic a hilar mass. Elevation of the left hilus and mainstem bronchus, shift of the posterior junction line to the left, and obscuration of the left upper lobe pulmonary artery and vein can assist in the diagnosis of LUL collapse. A juxtaphrenic peak is more frequently observed with LUL collapse. A fissural tag along the posterior aspect of the major fissure projects as a vertical oblique white line lateral to the aortic arch.

On the lateral exam, a characteristic finding of left upper lobe collapse is a retrosternal density which represents the collapsed lung anteriorly outlined by the major fissure which has also been displaced. The retrosternal density is actually produced by two structures- its superior component represents the collapsed lung and its inferior component is produced by the epi/pericardial-pleural reflection.

Left lower lobe atelectasis is a common complication observed in medical patients in the intensive care unit. This finding may be related to the combined effects of mechanical compression of the lung by the left ventricle and the tendency of suction catheters to enter the right lung selectively. Phrenic nerve palsey secondary to topical cooling during coronary artery bypass surgery can also play a role in this phenomena.

It is classically taught that LLL atelectasis produces a triangular shaped opacity behind the heart. LLL atelectasis can be mistaken for pleural effusion, particularly when the lateral margin of the collapsed LLL forms a concave interface with the LUL in the lateral costophrenic angle on the PA exam. Other findings which support a diagnosis of LLL collapse include displacement of the left hilum inferiorly, obscuration of the descending branch of the left pulmonary artery, and the presence of a mediastinal wedge. In marked LLL collapse the lobe becomes pancaked against the paraspinal area and only a short segment of the medial aspect of the left hemidiaphragm may be obscured- although the paraspinal interface and descending aorta will be obscured. Reorientation of the vessels in the hyperexpanding LUL may cause them to be seen end-on as a series of vascular nodules that parallel the left heart border. On the lateral exam, posterior displacement of the major fissure is evident and the collapsed lung will form an opacity over the posterior lower thorax.

The "top of the knob" sign is seen when mediastinal soft tissues shift over the upper aspect of the aortic arch and obscure its upper margin. The "flat-waist" sign is the result of left lateral shift and posterior rotation of the heart into the left hemithorax. As the heart rotates posteriorly (in response to LLL volume loss) the main pulmonary artery segment is projected further to the left than normal. Initially, this situation can cause straightening of the left heart border- resulting in the "flat-waist." "Nordenstrom's sign" is the presence of lingular atelectasis associated with LLL collapse. Linear atelectasis of the lingula often accompanies LLL atelectasis because the lingular bronchi become vertically oriented and often kink when the LUL hyperexpands in response to LLL volume loss.

REFERENCES:

(1) J Thorac Imaging 1996;11(3):176-186

(2) J Thorac Imag 1996; 11:p. 187-197

(3) J Thorac Imag 1996; 11 (3): 165-175

(4) J Thorac Imag 1997; 12: 59-63

(5) J Thorac Imag 1996; 11: 92-108

(6) J Thorac Imag 1996; 11: 109-144

(7) Radiology 1998; Blankenbaker DG. The Luftsichel sign. 208: 319-320 (No abstract available)

(8) Radiology 1999; Partap VA. The comet tail sign. 213: 553-554 (No abstract available)

(9) Radiology 2008; Hansell DM, et al. Fleishner society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. 246: 697-722