Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis can be divided into three sub-types: Acute, Chronic, and Acalculous.

Acute Cholecystitis:

Acute cholecystitis is most commonly due to an acute obstruction of the cystic duct due to cholelithiasis in about 95% of cases. Patients who present with acute cholecystitis almost always have previous episodes of biliary colic. In most cases no precipitating event occurred before the development of biliary colic, but in some cases the colic is provoked by a meal. Bacterial infection is usually present, but is not felt to play a significant role in the etiology of the disorder. The most common organisms are gram negatives such as E. coli and Klebsiella. The diagnosis of acute cholecystitis should be considered for patients who have symptoms for over 6 hours duration. Clinically, these patients complain of RUQ pain which may radiate to the right shoulder or interscapular area, nausea, vomiting, chills, and fever. Leukocytosis can occur, and the alkaline phosphatase, transaminase, and amylase levels may also be elevated. Mild hyperbilirubinemia can occur in up to 20% of cases.

Complications of acute cholecystitis

1. Emphysematous/Gangrenous cholecystitis: This complication is seen more commonly in elderly patients, with a particularly increased risk in diabetics (40% of cases). The etiology is generally secondary to cystic duct obstruction, but it may also occur secondary to GB ischemia in patients with severe ASPVD.

2. Perforation: Perforation occurs in up to 10% of cases of acute cholecystitis, generally 3 to 7 days after the onset of symptoms. The fundus is the most common site.

Radiographic Findings in Acute Cholecystitis

Plain Film: Emphysematous cholecystitis may be identified on plain film by the presence of gas in GB wall and lumen.

Ultrasound: The sensitivity of ultrasound in the detection of acute cholecystitis is between 81-97%, the specificity is only 64% (compared to 96-98% for hepatobiliary imaging), and the predictive value is only 40% (compared to 70% for scintigraphy).

On US findings in acute cholecystitis include:

1- GB wall thickening greater than 4 mm (normal is 2-3mm) which may be focal or diffuse (sensitivity 73%, specificity 67%). Although present in most patients with acute cholecystitis, gallbladder wall thickening is a non-specific finding as it may also be seen in chronic cholecystitis, CHF, GB carcinoma, ascites, hypoprotein/albuminemia, adenomyomatosis (focal), physiologic GB wall contraction, multiple myeloma/mets, HIV (Cryptosporidium, CMV), and leukemic infiltration (may also note hypoechoic zones within the gallbladder wall and pericholecystic fluid).

2- Hypoechoic surrounding serosal edema

3- Cholelithiasis (sensitivity 95%, specificity 38%) Cholelithiasis may be missed in up to 5% of patients with stones by sonography. A "wall-echo-shadow" complex (or "WES" sign) occurs in patients with a contracted gallbladder full of stones. In most cases, a "WES" sign is associated with chronic cholecystitis. The presence of stones is non-specific as they are also commonly found in the asymptomatic general population. A stone detected in the cystic duct (choledocholithiasis) confirms the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, but this is rarely seen (less than 5% of cases).

4- Pericholecystic fluid (up to 20-25% of cases, usually seen between the gallbladder and the liver, and it's presence implies a more advanced case of cholecystitis.

5- Echogenic bile

6- Positive sonographic Murphy's sign: The sonographic Murphy's sign refers to localized tenderness directly over the gallbladder elicited by pressure applied with the transducer during sonographic examination. This finding is subjective and technician dependent. The combination of gallstones and a positive sonographic Murphy's sign has a positive predictive value for acute cholecystitis of as high as 90-96% (Sensitivity 63-94%, Specificity 85-94%).

7- Gallbladder enlargement may also be seen (greater than 4 x 10 cm). The upper limit of normal for gallbladder size is 8-10 cm in length, and 4-5 cm in width. The width is the more important dimension as there is a greater degree of normal variation in gallbladder length.

Color doppler sonography may occasionally reveal hyperemia within the gallbladder wall, but this is more likely to be demonstrated with the use of power doppler. Overall, the sensitivity and specificity of sonography for the detection of acute cholecystitis are 81-100%, and 60-100%, respectively.

In emphysematous/gangrenous cholecystitis the GB wall is hyperechoic due to intramural gas and reverberation echos (dirty shadowing) from GB fossa is seen due to gas within the wall and lumen. Do not confuse this "dirty" shadow with the relatively "clean" shadow seen in the case of a porcelain gallbladder or large gallstone.

The sensitivity of ultrasound in the detection of acute cholecystitis is about 40-97%, the specificity is 64-100% (compared to 98% and 100%, respectively, for hepatobiliary imaging), and the positive predictive value is only 40% (compared to 70% for scintigraphy) [19].

Computed Tomography (CT) On CT, imaging of acute cholecystitis can demonstrate the presence of gallstones, gallbladder wall thickening, and the pericholecystic fluid. Transient enhancement of the liver adjacent to the gallbladder may also be seen [4].

Scintigraphy in Acute Cholecystitis:

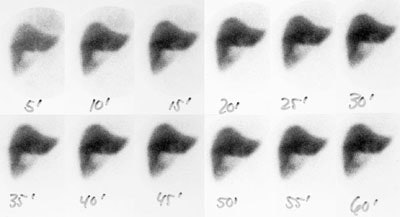

Visualization of the biliary system with non-visualization of the gallbladder after 4 hours is considered diagnostic of acute cholecystitis (Delayed visualization between 1-4 hours in a patient with normal liver function is a reliable sign of chronic cholecystitis). Morphine augmented cholescintigraphy (see below) can be used to shorten the duration of the examination.

The gallbladder will be anterior on the lateral examination. If it is difficult to distinguish activity within the proximal duodenum from the gallbladder, activity in the duodenum can be cleared by giving 200-300 ml of water by mouth.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of cholescintigraphy

for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis is greater than 95-98%

and 90-98%, respectively. In about 3.5% of cases of acute

cholecystitis the gallbladder may visualize between 1 and 4 hours-

possibly secondary to incomplete cystic duct obstruction. The

negative predictive value of a normal exam (ie: visualization of

the gallbladder within 1 hour) in excluding acute cholecystitis

is greater than 99%. A meta-analysis found that

cholescintigraphy has the highest diagnostic accuracy of all

imagingmodalities in the detection of acute cholecystitis [18].

Non-visualization of the gallbladder is a non-diagnostic finding when there is very poor or absent excretion of the tracer into the biliary tree which can be seen in common duct obstruction or severe hepatocellular dysfunction (bilirubin over 30 mg/dl).

|

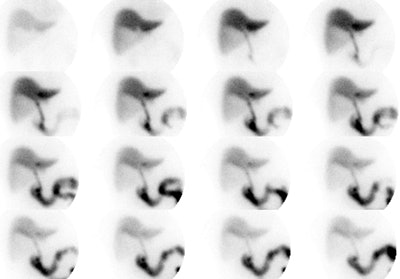

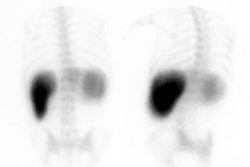

Acute Cholecystitis: The case below demonstrates the characteristic findings of acute cholecystitis. There is non-visualization of the gallbladder at one hour. There is a subtle rim of increased tracer activity about the gallbladder fossa ("rim sign"- see below). The gallbladder is markedly distended. There is mild hang-up of tracer in the left hepatic ductal system. Click the image to view the cine of this case (1 MB). Case courtsey of Dr. Jamie Montilla, MD |

|

|

Characteristic Scintigraphic Findings in Acute Cholecystitis:

Rim Sign:

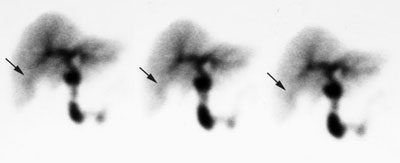

Refers to increased pericholecystic hepatic activity without GB visualization- the rim sign is caused by severe inflammation extending into the adjacent liver, resulting in increased blood flow to that area, and increased delivery of radiotracer [20]. The rim sign appears as curvilinear band of increased activity along the hepatic margin above the GB fossa and is usually identified early in the examination (See image below). It may be due to increased flow and/or impaired hepatocyte radionuclide excretion. The rim sign is identified in about 25-35% of patients with acute cholecystitis [20], but it can also be seen in some patients with chronic cholecystitis. The positive predictive value for acute cholecystitis is about 95% when a rim sign is identified in association with non-visualization of the gallbladder at one hour [9]. Approximately 40% of patients who demonstrate the rim sign will have complicated cholecystitis (extensive necrosis, perforated or gangrenous GB), thus the presence of this sign indicates the need for more emergent surgery. Very rarely there may be gallbladder visualization in association with a rim sign- this should still be considered highly suspicious for acute or subacute cholecystitis. [6]

Rim sign in acute cholecystitis

Increased blood flow:

Increased blood flow to the region of the gallbladder fossa on the radionuclide angiogram, increases the positive predictive value of non-visualization of the gallbladder for acute cholecystitis. Increased flow is seen in 88% of patients with gangrenous cholecystitis, however, only 30% of patients with increased flow had gangrenous cholecystitis.

Dilated cystic duct sign:

The dilated cystic duct sign refers to a nubbin of activity projecting from the proximal end of the common bile duct medial to the gallbladder fossa. It is believed to represent the a patent cystic duct distal to the site of the obstructing stone [19]. This sign is observed in about 7% of patients with acute cholecystitis and should not be mistaken for a small, shrunken gallbladder. Ultrasound may be useful to demonstrate gallbladder size in these cases.

Differential diagnosis of Non-visualization of the GB at one hour:

- Recent meal (patients should be NPO at least 4-6 hours prior to the exam)

- Prolonged fasting over 20 to 24 hours (Gallbladder is filled with bile. Can give Sincalide 30 to 60 minutes before the examination to empty gallbladder).

- Prolonged hyperalimentation: Prolonged hyperalimentation with fasting leads to decreased bile production and cholestasis. There is no CCK-mediated GB contraction due to lack of food entering the duodenum. This results in bile stasis and sludge formation due to water resorption. The radiotracer cannot enter the distended, sludge filled gallbladder. Can give Sincalide 30 to 60 minutes before the examination to empty gallbladder).

- Prior cholecystectomy

- Acute Pancreatitis

- Administration of immediately CCK prior to the start of the examination (Gallbladder is still contracted and does not accumulate tracer) [7]

- Common/Cystic duct obstruction: Cholangiocarcinoma of cystic duct or mass compressing cystic duct

- Severe hepatocellular dysfunction (Hepatitis, Cirrhosis): May

result in both markedly delayed or non-visualization of the

gallbladder [20]. Delayed imaging is often required in this

setting [20].

- Congenitally absent GB

False positive exam for cholecystitis:

An increased incidence of falsely positive exams is seen in patients with severe intercurrent illness (specificity is reduced to 70% in this setting [20]), who are fasting, or who are on hyperalimentation for greater than 24 hours [20] (the specificity of the examination in these clinical settings is poor).

False negative exam for cholecystitis: (Normal study in patient with disease)

In general, false-negative studies (visualization of the gallbladder in a patient with acute cholecystitis) occur in less than 5% of patients, and may be associated with [19]:

- Incomplete cystic duct obstruction

- Acalculous cholecystitis

- Accessory cystic duct

- Duodenal diverticulum or biliary duplication cyst simulating GB activity

Chronic Cholecystitis:

On ultrasound chronic cholecystitis may demonstrate irregular GB wall thickening and Rokitanski-Aschoff sinuses (best seen on OCG). A poorly marginated, complex RUQ mass with intense internal reflections is indicative of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis which can mimic gallbladder carcinoma.

The majority of patients with chronic cholecystitis exhibit normal visualization of the gallbladder (85-90%). Delayed visualization of the gallbladder (Between 1 to 4 hours of the exam) is considered fairly characteristic for chronic cholecystitis when seen, but delayed visualization can also be seen in a very small number of patients with acute cholecystitis (3.5%). The longer the delay in visualization, the higher the correlation with chronic cholecystitis. Visualization of bowel activity during the first hour of imaging prior to visualization of the gallbladder is a non-sensitive, but rather specific finding in patients with chronic cholecystitis (in most normals, the gallbladder is seen before bowel activity). The delayed gallbladder filling is caused by a functional resistance to flow through the cystic duct often due to viscous concentrated bile, gallstones, chronic mucosal thickening, or fibrosis [20]. This sign indicates chronic cholecystitis about 75% of the time.

Delayed biliary-to-bowel transit time (bowel activity not seen at one hour despite visualization of the gallbladder) has also been described in patients with chronic cholecystitis, and it is possibly related to an associated ampullitis. Unfortunately, this finding can be seen in many other conditions including:

- Normal- 15-20% of healthy subjects can demonstrate delayed

biliary to bowel transit [20].

- Hyperacute obstruction of the common bile duct

- Sphincter of Oddi dyskinesia: Spasm of the sphincter of Oddi (dyskinesia) is characterized by reflux into the intrahepatic bile ducts during gallbladder contraction with sincalide infusion and subsequent paradoxical filling of the gallbladder immediately after cessation of the infusion [12].

- Morphine given prior to exam

- Sincalide given prior to exam: A functional delay in biliary

to bowel transit occurs in up to 50% of patients who received

sincalide to empty the gallbladder before cholescintigraphy [20]

due to preferential shunting of bile into the recently emptied

gallbladder.

- S/P sub total gastrectomy and vagotomy

- Sepsis

- Small bowel obstruction

Gallbladder Ejection Fraction/Chronic Acalculus Cholecystitis:

Chronic acalculous cholecystitis is relatively uncommon in comparison to chronic calculous cholecystitis and accounts for 5-10% of cases of symptomatic chronic cholecystitis [1]. Patients will often complain of RUQ pain and biliary colic, but have a completely normal work-up, including a normal ultrasound and hepatobiliary study. Many of these patients are found to have chronic inflammatory changes in their gallbladder if they are taken to surgery. Patients with chronically inflamed, partially obstructed, or functionally impaired gallbladders (gallbladder dyskinesia) will demonstrate an abnormal gallbladder ejection response to CCK. An abnormal gallbladder ejection fraction is considered less than 35% and is not affected by age. Once the GBEF becomes abnormal, it does not return to normal and will continue to decrease over time [15].

A gallbladder ejection fraction of less than 35% is associated with chronic acalculous cholecystitis in 94% of patients [3] and is a fairly good predictor of a favorable symptomatic response to surgery (Sensitivity 72%, Specificity 76-89%). However, other authors feel that the GBEF is of questionable value in predicting a therapeutic response to surgery [5].

For the exam, an IV infusion of Sincalide (0.02 ug/kg) is given

in order to determine the gallbladder ejection fraction. Rapid

injection of Sincalide may cause spasm of the cystic

duct/gallbladder neck which will impair emptying of the

gallbladder and falsely lower gallbladder ejection fraction [1].

Previously, the injection was given slowly over 3 to 5 minutes.

However- some authors feel that a 3 to 5 minute infusion is too

rapid and that up to one-third of normal patients may have a

falsely decreased ejection fraction of less than 35% [1,10]. Also-

abdominal cramping and nausea can be seen in 50% of healthy

subjects [20].

Ziessman [1,2,10] feels that a slow, 30, 45, or 60 minute infusion of Sincalide (0.01 to 0.02 ug/kg) is preferable because it is more physiologic, results in more complete gallbladder emptying, produces less variability in calculated ejection fraction, and has fewer side effects [1,10,20]. The use of a slow infusion (20 minutes) has also been supported by other authors [13]. The normal GBEF value is dependent on the dose and duration of infusion performed [10]. For a 0.01 ug/kg infusion rate a normal GBEF is greater than 31-38% (for a 45 minute infusion), and between 44-49% (for a 60 minute infusion) [10]. He also found this method resulted in fewer false-positive examinations. A recent multicenter study concluded that a 0.02 ug/kg infusion given over 60 minutes resulted in the lowest variation in GBEF and that this should become the standard for clinical use [17,20]. Using this type of infusion, the lower limit of normal for GBEF is 38% [17,20]. This same article found no significant difference in GBEF between men and women (or for age) [17]. Reproduction of patient symptoms during Sincalide infusion is not diagnostic of chronic cholecystitis [1] - pain seen with sincalide is dependent on dose rate and not to the presence of underlying disease [20]. Click here for GBEF protocols.

Images are then acquired over the gallbladder for 30 minutes and

an ejection fraction determined by placing a region of interest

over the gallbladder. Side effects are common (50-60% of patients)

and include nausea, epigastric cramping or pain, and occasionally

vomiting. Using this method an abnormal GBEF has been considered

to be less than 35%.

An alternative to the use of sincalide is to have the patient consume a fatty meal to stimulate gallbladder contraction [12,14] (a meal with at least 10 gm of fat is required to contract and empty the gallbladder [20]). However, fatty meal ejection fractions can vary widely (from 24% to 92%) and can be affected by the meal content and the duration of imaging [12]. At least 60 minutes of imaging after consumption of the meal is recommended [12] as maximal gallbladder emptying is generally seen 55 to 60 minutes following consumption of the meal [14]. For a lactose-free Ensure Plus meal the normal gallbladder ejection fraction is greater than 33% [14] and this is very similar to the ccepted lower limit of normal for Sincalide stimulated GBEF (greater than 35%).

An abnormal gallbladder ejection fraction is not necessarily diagnostic of chronic cholecystitis [1]. Chronic diseases such as sprue, diabetes, achalasia, sickle cell disease, and irritable bowel syndrome have also been associated with a low GBEF [1]. Certain drugs can also falsely lower GBEF including morphine, atropine, octreotide, nifedipine, progesterone, and phentolamine [1]. It is very important to ensure that the patient has not taken opioids during the 24 hours prior to the exam as these agents can result in a falsely decreased GBEF [15].

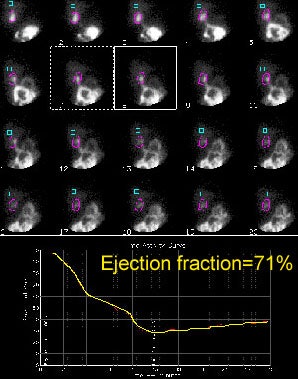

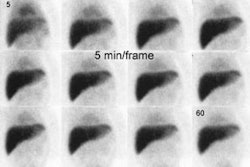

|

Gallbladder ejection fraction: To determine the gallbladder ejection fraction an ROI is drawn about the gallbladder and a time activity curve is generate. The GBEF is then determined. In this case the GBEF was 71% which is normal. Post CCK infusion cine images can be viewed by clicking on the image below (100KB). Case courtsey of Dr. Jamie Montilla. |

|

|

Medications and Physiologic States which can alter gallbladder contractility:

- Morphine: Produces spasm of the sphincter of Oddi. Morphine

has a 4 to 6 hour half-life, but approximately 50% of patients

who receive sincalide subsequent to having been administered

morphine during cholescintigraphy have normal gallbladder

contraction [20].

- Atropine: Inhibits gallbladder emptying

- Calcium channel blockers: Reduce contractility by interfering with calcium mediated smooth muscle contraction

- Diabetes: Neuropathy has been associated with decreasing contractility

- Truncal vagotomy: Results in decreased gallbladder contractility and increased gallbladder volume due to disruption of the cholinergic pathway.

- Achalasia- decreases ejection fraction by 50% [8]

- Octreotide therapy [8]

- Cholinergic medications: Enhance gallbladder emptying

- Hypercalcemia: Enhances contraction

Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis:

Acalculous cholecystitis accounts for only 2-5% of all cases of acute cholecystitis and it is typically associated with surgery (Post-op), massive trauma, extensive serious burns, sepsis/shock, hyperalimentation, DM, pancreatitis, or Sickle Cell. It may be due to combination of stasis with increased bile viscosity and chemical irritation due to hyperconcentrated bile, bacterial infection, and ischemia. Edema or non-calculous obstruction of the cystic duct may also play a role in its etiology. Cystic duct obstruction may sometimes be incomplete, allowing some tracer to enter the gallbladder and resulting in a false negative exam [20]. A sincalide infusion will often demonstrate little or no gallbladder contraction, but this finding may also represent chronic cholecystitis. A labeled white blood cell exam may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Cholescintigraphy has a sensitivity of between 60 to 92.5% (generally 70%-80% [20])- for acute acalculous cholecystitis [3]. In patients with a clinically suspected false negative exam, the presence of a rim sign will help to confirm the diagnosis [20]. Ultrasound findings in acalculous cholecystitis include median level echos (pus) within the GB lumen.

Choledocholithiasis/Biliary Obstruction:

Ultrasound has a low sensitivity for detecting common duct stones (11 to 30%) and acutely, there may be no intrahepatic ductal dilatation. Extrahepatic bile duct obstruction causes an increase in the ductal hydrostatic pressure until the point where further hepatocyte excretion is no longer possible. In acute common bile duct obstruction (0 to 24 hours) there is generally prompt hepatic uptake of the tracer without visualization of the biliary tree and no GI activity (unless obstruction is partial). Hepatic function remains normal during this early period. Between 24 and 96 hours, there is a mild to moderate decrease in hepatic function. Beyond 96 hours, there is very poor hepatic uptake and the scintigraphic findings are difficult to distinguish from hepatitis.

If the bile ducts are visualized, tracer activity within a normal common duct should be less on a 2 hour image, than on a 1.5 hour image. If ductal activity is unchanged or more intense on later images, some degree of obstruction is likely present. Intrahepatic cholestasis can produce a pattern identical to complete CBD obstruction.

|

Choledocholithiasis: The hepatobiliary exam demonstrated prompt uptake of the radiotracer with no excretion. The findings were consistent with acute common bile duct obstruction. Despite this diagnosis, a CT scan was performed to exclude a pancreatic neoplasm. A stone can be seen in the distal common bile duct on the CT exam (blue arrow). Click CT to enlarge. |

|

|

Ddx: Prompt Hepatic uptake without excretion:

- Acute common bile duct obstruction: Choledocholithiasis

- Acute pancreatitis

- Carcinoma: (Cholangiocarcinoma, ampullary carcinoma, or carcinoma of the head of the pancreas) More commonly the tumors produce gradual obstruction with hepatocellular dysfunction and delayed hepatic accumulation of the radiotracer.

- Infection: Ascending cholangitis cannot be excluded when there is delayed or non-visualization of bowel activity

- Cholestasis: More commonly there is decreased hepatic uptake (slow blood clearance) with slow biliary excretion associated with cholestasis. Causes of cholestasis include gram-negative sepsis and drugs. Agents such as chlorpromazine (Dilantin) and birth control pills are often associated with decreased hepatic function and delayed accumulation of tracer.

Partial common bile duct is more difficult to determine as normal

biliary to bowel transit does not exclude the diagnosis [20]. Poor

clearance from the biliary tree is a diagnostic finding [20].

However, biliary duct retention and delayed biliary-to-bowel

transit at 60 minutes is seen in up to 20% of healthy subjects

[20].

REFERENCES:

(1) J Nucl Med 1999; Ziessman HA. Cholecystokinin

cholescintigraphy: Victim of its own success? 40: 2038-2042

(2) J Nucl Med 1992; Ziessman HA, et al. Calculation of a gallbladder ejection fraction: advantage of continuous sincalide infusion over the three-minute infusion method. 33: 537-41

(3) Radiol Clin North Am 1993; Kim EE, et al. Nuclear hepatobiliary imaging. 31: 923-33

(4) AJR 1995, Feb: p.343

(5) Am J Gastroenterol 1990; Westlake PJ, et al. Chronic right upper quadrant pain without gallstones: does HIDA scan predict outcome after cholecystectomy? 85: 986-990

(6) Radiology 1998; Dorio PJ. The rim sign. 209: 801-802

(7) J Nucl Med 1997; Chen CC, et al. Morphine augmentation increases gallbladder visualization in patients pretreated with cholecystokinin. 38: 644-647

(8) J Nucl Med 1997; Kim CK. Pharmacologic intervention for the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis: cholecystokinin pretreatment or morphine, or both? 38: 647-649

(9) J Nucl Med 1993; Morrison JC, et al. Prompt visualization of the gallbladder with a rim sign- acute or subacute cholecystitis? 34: 1169-1171

(10) Radiology 2001; Ziessman HA, et al. Normal values for sincalide cholescintigraphy: Comparison of two methods. 221: 404-410

(11) Gastroenterology 1991; Yap L, et al. Acalculous biliary pain: cholecystectomy alleviates symptoms in patients with abnormal cholescintigraphy. 101: 786-793

(12) J Nucl Med 2002; Krishnamurthy GT, Brown PH. Comparison of fatty meal and intravenous cholecystokinin infusion for gallbladder ejection fraction. 43: 1603-1610

(13) J Nucl Med 2003; Pons V, et al. Quantitative cholescintigraphy: selection of random dose for CCK-33 and reproducibility of abnormal results. 44: 446-450

(14) J Nucl Med 2003; Ziessman HA, et al. Cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy: methodology and normal values using a lactise-free fatty meal food supplement. 44: 1263-1266

(15) J Nucl Med 2004; Krishnamurthy GT, et al. Constancy and variability of gallbladder ejection fraction: impact on diagnosis and therapy. 45: 1872-1877

(16) J Nucl Med 2006; Krishnamurthy S, Krishnamurthy GT. Effect of sequential administration of an opiod and cholecystokinin on gallbladder ejection fraction: brief communication. 47: 1463-1466

(17) J Nucl Med 2010; Ziessman HA, et al. Sincalide-stimulated

cholescintigraphy: a multicenter investigation to determine

optimal infusion methodology and gallbladder ejection fraction

normal values: 51. 277-281

(18) Radiology 2012; Kiewiet JJS, et al. A systemic review and

meta-analyis of dignostic performance of imaging in acute

cholecystitis. 264: 708-720

(19) Radiographics 2013; Uliel L, et al. Nuclear medicine in the

acute clinical setting: indications, imaging findings, and

potential pitfalls. 33: 375-396

(20) J Nucl Med 2014; Ziessman HA. Hepatobiliary scinigraphy in 2014. 55: 967-975