Congenital Lobar

Emphysema (Congenital lobar overinflation):

View

cases of congenital lobar emphysema

Clinical:

Some

have suggested that the condition should be referred to as "congenital

lobar overinflation" because on histologic analysis alveolar destruction is not always

present- rather, alveoli are overdistended, but

intact [3,4]. Patients usually are identified in the neonatal period or within

the first month of life. Males are affected more than females (3:1) [2,4]. Symptoms include intermittent respiratory distress, tachypnea, and progressive cyanosis. The symptoms may

improve over time as the normal lobes continue to develop, however, persistent atelectasis in the adjacent lung may lead to recurrent

infections. Congenital heart disease (PDA or VSD) is also found in 12-15% of

affected patients. The most common location for congenital lobar emphysema

(CLE) is the left upper lobe (40-42%), followed by the right middle lobe

(30-35%), and the right upper lobe (20%). The lower lobes are only rarely

involved (less than 1% of cases [3]). Involvement of two lobes is rare (5% of

cases). Numerous etiologies for CLE have been postulated including:

1- Congenital segmental absence or hypoplasia of the bronchial cartilage (bronchial atresia/stenosis) which may be the result of focal interruption of the bronchial artery supply late in fetal life.

2- Poly-alveolar lobe (excess alveoli) - the alveoli are normal in size or small, but are increased in number 3 to 5 fold [3].

3- Extrinsic bronchial compression: Patent ductus arteriosus, aberrant left pulmonary artery, pulmonary artery dilatation (associated with absent pulmonary valve), and bronchogenic cyst.

CLE most commonly manifests with respiratory distress during early childhood, with about 50% of cases presenting during the first 2 days of life [5]. Symptomatic patients with CLE are treated with lobectomy [3]. Asymptomatic children or those with only minor symptoms can be managed conservatively [3]. Approximately 15% of children with CLE have associated congenital heart disease such as a PDA or VSD [5]. Followup imaging in this group has shown gradual reduction in the size of the involved lobe with time [3].

X-ray:

Fetal

US may show a homogeneously hyperechoic mass within

the lung [4]. On fetal MR, it can appear as a mass with a

homogeneously high signal intensity on T2 images [4].

CLE may initially appear as an solid/opaque mass due to trapped fluid during the first few days of life [4]. The fluid progressively clears via the tracheobronchial system, lymphatics, and capillary network [3]. Subsequently, the affected lung increases in size as it distends with air and on CXR there is an over-expanded radiolucent area with decreased pulmonary vascularity (the expanded lobe is hyperlucent). Other findings of over-distention are also seen- shift, compression of adjacent lung (compressive atelectasis), etc... Streaky densities seen early within the lesion represent dilated lymphatics.

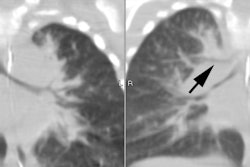

On CT, CLE appears as a hyperlucent enlarged lobe with attenuated or thinned vascular structures coursing through the affected area (a finding that is not seen in CCAM or pneumothorax) [4].

Differential considerations for a unilateral hyperlucent lung include:

1- Parenchymal causes: Congenital lobar emphysema, ball-valve lumenal obstruction (foreign body), and bulla/ emphysematous changes

2- Vascular causes: Hypoplastic pulmonary artery, pulmonic stenosis with preferential flow, pulmonary embolism, bronchiolitis obliterans, and compression of pulmonary vessels by tumor.

3- Chest wall deficiency: Polland's syndrome or Post-operative.

REFERENCES:

(1) AJR 1999; Donnelly LF, et al. Localized radiolucent chest lesions in

neonates. Causes and differentiation. 172: 1651-1658

(2) Radiographics 2002; Zylak CF. Developmental lung anomalies in the adult: radiologic-pathologic correlation. 22: S25-S43

(3) Radiol Clin N Am 2005; Paterson A. Imaging evaluation of congenital lung abnormalities in infants and children. 43: 303-323

(4) Radiographics 2010; Biyyam DR, et al. Congenital lung abnormalities: embryologic features, prenatal diagnosis, and post natal radiologic-pathologic correlation. 30: 1721-1738

(5) Radiographics 2011; Dillman JR, et al. Expanding upon the unilateral hyperlucent hemithorax in children. 31: 723-741