Famed quarterback Joe Namath had a double knee replacement at age 50, which probably tells you everything you need to know about the long-term deleterious effects of American football on the knees. But the sport that the rest of the world calls football may be even more crippling.

In fact, soccer players who return to competition after catastrophic knee injuries -- especially the very common anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear -- may be putting their joints at considerable risk.

"Soccer has the worst rate of arthritic conditions of any sport in the world for people who had ACL reconstructions," stated Dr. Scott F. Dye, associate clinical professor of orthopedic surgery at the University of California, San Francisco in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "Soccer is a knee killer."

This knee killer is being aided and abetted, Dye suggested, by orthopedic surgeons and the imaging they have come to rely upon.

"I think the abundance of the MRI has led to a diminishment of diagnostic skills," Dye said. "The accepted methods of treatment can involve an overinterpretation of the overabundant structural data without a proper history and thorough physical exam being taken."

Dye sees the knee (and all joints) as a "living biological transmission system" that needs to be understood both structurally and metabolically. An ACL tear is now considered an easy fix, but Dye said the current standard of care -- an aggressive approach that advocates returning athletes to sport in a matter of weeks -- ignores serious long-term consequences.

"The knee doesn’t know the difference between an ACL repair and an axe attack," Dye said. "The standard treatment is antithetical to the proper way of managing these cases."

In a report on knee function after ACL injury, Dye stated that "the loss of tissue homeostasis is often undetectable with use of structural imaging studies, such as plain radiography and magnetic resonance imaging."

"This loss ... can be a prelude to the eventual development and progression of irreversible degenerative changes," he continued (The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, September 1998; Vol. 80:9, pp. 1380-1393).

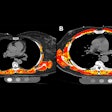

Dye's solution? Technetium scintiscans. Bone scans will show what x-rays and MRI do not -- evidence of damage to the tibia and femur that may cause an athlete future pain and decreased performance. This is what Dye calls the "pathophysical price" of knee injuries.

|

| Technetium bone scan images show increased metabolic activity of the medial femur and tibia in patient whose bone signal on MRI appeared normal. Images courtesy of Dr. Scott Dye. |

|

While ACL repair restores structural integrity to the knee, it does not restore full natural function. As Dye noted, "no animal model has demonstrated restoration of normal anatomical or biomechanical characteristics after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament."

Likewise, it's likely that no athlete is ever the same after ACL repair. So athletes concerned with the long-term health of their knees cannot resume what they once considered "normal" activity.

Dye has developed what he calls a "load envelope" to determine how much stress a reconstructed knee can endure and still maintain tissue homeostasis or health throughout the entire joint.

The system is a simple, two-planed graph that balances load transference with activity frequency. It resembles a supply and demand graph, with perfect equilibrium called the "zone of homeostasis." When demand greatly exceeds supply, the pathophysical price shoots up and the knee enters the "zone of physical failure."

Monitoring the athlete’s pain symptoms, as well as bone scans, are the key diagnostic tools to determining the optimal load balance.

In the case of a 32-year-old soccer player who had an ACL reconstruction of his left knee, bone scan images show the trauma caused by the injury and the surgery, followed by a return to normalcy under a regimen that including biking and swimming, but not soccer.

The envelope can even rule out surgical repair of a ruptured ACL. "If you drop the load low enough, you can have major failure that doesn’t require surgery," Dye said.

Dye is also a proponent of PET scans, which illustrate metabolic activity at a much higher resolution than scintigraphy, and is waiting for the day when he can view a 3D metabolic hologram of the knee.

"We’re on the cusp of a new era," he said. "We're at the end of a pure structural paradigm. Once the technology catches up, we'll see a new approach and understanding to treating the knee."

The approach is gaining worldwide acceptance. Dr. Sandy Glasson, a Virginia Beach, VA, orthopedist and physician to the U.S. women’s soccer team competing in Athens, believes that athletes can return to the field in four months and approach 100% performance in about six.

"It used to be a career-ending injury, and certainly an ACL tear is a big blow physically and mentally, but as long as you have it done in a timely manner and rehab correctly, you can return with no deficits," Glasson said. "Of course, after surgery, there'll be signs of bone bruising and damage to the joint surfaces, but with proper care those go away in time."

With the increased recognition of the ongoing trauma of an ACL injury, there is also a renewed emphasis on preventive training, especially for female athletes who suffer disparate levels of ACL injuries when compared to males of the same age.

Dye attributes this phenomenon in part to Title IX requirements that have opened sports opportunities to a larger number of women. Teenage girls who didn't play sports while younger, but take up soccer or basketball in high school, may lack the intuitive knowledge that helps prevent injury.

"This has sexist overtones, but there’s something to the saying that someone 'throws like a girl,'" Dye said. "Guys are more likely to program their cerebellum at an early age. With women, the cerebellum literally doesn't know the proper way to throw a ball because it takes a lot of repetition."

Likewise, athletes who "jump like a girl" are more prone to injury. An ACL tear is known as a deceleration injury, typically occurring not through a direct hit, but from a hard, straight-knee landing.

Learning how to land may be critical for avoiding ACL injuries. A number of studies have shown that proprioceptive neuromuscular conditioning of knee function can prevent serious injuries.

Glasson noted that other hypotheses exist regarding the gender disparity, ranging from the simple -- that a woman’s knee is physiologically weaker than a man’s and so more prone to injury -- to the dubious -- that ACL tears are affected by the menstrual cycle.

She believes that the higher rates of injury in women may also be a case of athletes pressing their performance beyond their development level.

"There’s a question as to whether their strength is at the same level as their skill. We have girls in high school playing at what used to be college level, and it could be that their bodies haven’t caught up to their moves," she said. "We’ll never know because we can’t do an experiment and control all the variables."

By Matt King

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 24, 2004

Related Reading

MRI, clinical examination confer equal diagnostic benefit in orthopedic injuries, February 11, 2003

Turf Wars in Radiology, Part V: Radiologists, orthopedists put best foot forward, October 1, 2002

Scenes from the Polyclinic: a case study, February 19, 2002

Olympic skiers tear up slopes -- and knees, February 18, 2002

Copyright © 2004 AuntMinnie.com