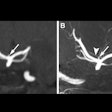

While 1.5 tesla is an adequate magnet strength, the combination of 3-tesla and parallel imaging has been a boon for advanced contrast-enhanced MRA. "When you do parallel imaging, you lose signal-to-noise. With 3T, you buy back the signal-to-noise," said Dr. Patrick Turski, professor of radiology at University of Wisconsin Medical School in Madison. "You end up with a very fast imaging technique that gives you high resolution and provides you with the ability to do temporal imaging for a series of 3D acquisitions."

One UW research group is developing what Turski called a "radial case-based technique" for image acquisition up to 80 times faster than conventional techniques. "With the radial acquisition, we are able to get an entire 3D volume in 0.26 to 0.4 seconds," he said. "It will allow you to study lesions, such as arterial venous malformations and AV fistula, with much higher anatomic delineation," and it reduces the need for catheter-based invasive digital subtraction angiography.

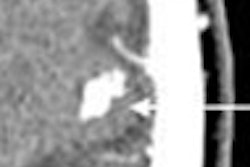

UCLA uses whole-body MRA in patients with peripheral vascular disease. The study generally includes hand and chest, abdomen and pelvis, and the lower extremities. The primary consideration is to acquire a good runoff study to show serious occlusions and stenoses, but image details may not be as adequate as with a dedicated carotid or chest study.

"That's the compromise," said Dr. Paul Finn of the University of California, Los Angeles. "If we do whole-body MRAs at one sitting, you can only optimize for one or two regions. Because of timing issues, you compromise on the other one, and we tend to compromise on the head and chest."

UCLA clinicians will employ a 20-second breath-hold while performing a dedicated contrast-enhanced carotid MRA, and stay focused on the carotid and chest. When doing a runoff study, the key is to avoid venous contamination in the calves. The time it takes the contrast to travel from the aorta of the chest to the calves varies in each patient. "In lots of cases, by the time you head to the calves, the veins would have filled," Finn said. "You might find yourself with very nice images of the carotids and chest, but poor images of the calves. So you have to prioritize and nail the primary question."

-- Wayne Forrest