In patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), hematoma expansion in the first critical hours after symptom onset is associated with significantly poorer outcomes. ICH is the most fatal form of stroke, and hematoma expansion occurs in as many as 40% of ICH patients after presentation.

Thanks to CT imaging and a new drug in the pipeline, however, it may be possible to identify and treat ICH patients at risk of hematoma expansion while there is time to improve outcomes, according to two new studies.

At the 2007 International Stroke Conference in San Francisco earlier this month, neurosurgeon Dr. Joshua Goldstein from the emergency department of Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) in Boston presented his group's study of 104 patients identified as having "contrast extravasation" seen as a spot sign at head CT -- defined as any high-contrast spot unassociated with a vascular structure. Presence of the sign was a reliable detector of ICH and hematoma expansion, the team concluded.

In a poster discussion at the same meeting, Dr. Richard Aviv from the University of Toronto in Ontario and the neuroradiology department of Sunnybrook Hospital in Toronto spoke with AuntMinnie.com about his group's study of hematoma expansion in 39 ICH patients who underwent CT at admission. Aviv's team employed a more nuanced categorization of the various CT findings they called a spot sign, but the results were quite similar to the MGH group's -- ICH patients with the sign fared significantly worse than those without it.

"Hematoma expansion is highly predictive of neurological deterioration, and is an independent predictor of mortality and functional outcomes," making it "an attractive target for therapy," Goldstein said in his talk. "Accurate and reliable clinical and radiographic predictors of ICH are needed to select patients at the highest risk of morbidity.... A marker of expansion risk would enable withholding of treatment from patients unlikely to benefit."

"With recombinant factor VIIa (NovoSeven, Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) emerging as the new treatment option for acute ICH, it will be particularly important to better predict which patients will benefit from such treatment," he said. The results of a phase III trial are pending.

Preliminary studies have shown that the agent can help stop bleeding in ruptured vessels in the brain without invasive surgery, speeding up the coagulation process from within. Due to the risk of blood clots in other areas of the body, however, the goal is not to treat every ICH patient, only those who are at risk of hematoma expansion, the researchers agreed.

Why not treat everyone? VIIa treatment is expensive -- "about $4,000 per patient," Aviv said. "There's a significant risk of DVT (deep venous thrombosis) and it's a very rigid regime. So if we can avoid treating patients that don't need the drug, we save money and we only treat patients that will benefit from it."

Goldstein and colleagues examined 104 consecutive patients with primary ICH, most of whom presented to the emergency department within three hours of symptom onset. All underwent CT angiography (CTA) of the head at presentation and in early follow-up within 48 hours.

Three neurosurgeons blinded to follow-up results for hematoma expansion reviewed the images and documented the presence of high-density spot signs at CT, measuring the volume at presentation and follow-up. Hematoma expansion was defined as an increase in hematoma volume greater than 33% from baseline.

The location of ICH was lobar in 47% of the patients, most of the rest were deep. Eighty-eight percent of the patients presented within three hours of symptom onset. Hematoma expansion occurred in 13% of the patients, with hematoma volume in these patients increasing by a median of 51% (interquartile range, 31% to 102%).

Contrast enhancement was seen in 56% of the patients and was associated with an increased risk of hematoma expansion (22% versus 2%, p = 0.003). The contrast enhancement spot sign was 93% sensitive and 50% specific for predicting expansion -- with a low (24%) positive predictive value, but extraordinarily high (98%) negative predictive value for hematoma expansion of a third or more, Goldstein reported.

As expected, patients who were initially scanned within three hours of symptom onset were more likely to have subsequent expansion (27% versus 13%, p = 0.007). Still, "contrast extravasation was the only significant predictor of subsequent hematoma expansion" (OR 18, 95% CI 2.1-162), he said.

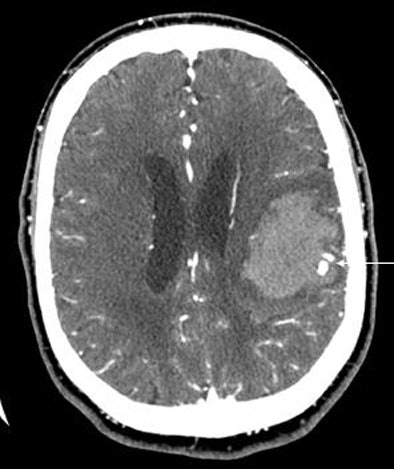

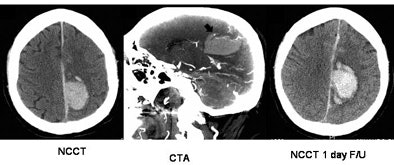

|

| A 64-year-old man presented with acute onset of right arm weakness and aphasia. The patient underwent CT/CTA. Neuroradiologists were initially concerned the CT findings (arrows, above and below) represented an AV malformation. Further examination left them unable to track the contrast through any vascular distribution, however, and they hypothesized that the findings represented contrast extravasation. Two hours later the patient suffered significant clinical deterioration; repeat head CT showed hematoma expansion. Direct angiography showed no AVM, and subsequent surgical excision found only hematoma and no vascular malformation. In 104 patients, lack of a spot sign had a 98% negative predictive value for identifying patients who would not have hematoma expansion at follow-up. Image courtesy of Dr. Joshua Goldstein. |

|

The effect was independent of time to presentation, and moreover, the presence of contrast extravasation was the only independent predictor of hematoma expansion, according to Goldstein.

"Use of this marker may extend the time window for hemostatic therapy, potentially doubling the number of patients," he said.

A spot by any other name

A limitation -- and potential strength -- of the Boston study was its classification of all high-density areas as contrast extravasation.

"We operationally defined the term extravasation for purposes of this study as the presence of any high-density material in the hematoma following CTA which is not clearly attributable to a blood vessel," Goldstein said. "One of the questions is whether you can, in the absence of formal surgical pathology, declare this (to be) contrast extravasation."

Thus the term extravasation was useful for documenting "contrast where it doesn't belong," Goldstein told Aviv and AuntMinnie.com in an interview. "Some people have spots, some people have this kind of blush, some people have speckles all throughout the hematoma, some people have these big spots. And we were having difficulty assigning them."

The spots seem to indicate something about the way the hematoma is functioning, Goldstein added. "We wonder if some are collapsed veins ... with a bit of contrast."

Aviv's group distinguished the smaller high-density spots from the larger "blush" regions. Only the latter, occurring in about half of the patients, were deemed extravasation in the Toronto study.

"This is not extravasation," Aviv said of the smallest spots. "We believe this represents primary cerebrovascular injury, whether it's amyloid-related angiopathy, or due to Charcot-Bouchard aneurysm, or the possibility of inflammatory markers resulting in damage. The fact that it occurs suggests primary rather than secondary etiology."

"I like Dr. Aviv's term 'spot sign' as it reflects the fact that there is a finding without commenting on its pathophysiology, as I cannot confirm that it represents active extravasation," Goldstein later commented in an e-mail. "I think he and I are looking at much the same thing, but he is being much more selective than I was in the finding he is using (which may end up being justified, as the 'spot sign' alone appears to have higher specificity than 'any contrast within the hematoma,' which I used)."

Toronto spots

The University of Toronto and Sunnybrook researchers prospectively examined 39 patients (26 women, 13 men) presenting with ICH within three hours. They were investigated with CTA stroke imaging and early follow-up CT. The scans were reviewed by three readers, who dichotomized the patient cohort depending on the presence or absence of the spot sign. The researchers compared the clinical and radiological outcomes of both groups.

They found the spot sign in a third of all patients (13/39) with high interobserver agreement (κ = 0.92-0.94). The baseline clinical variables were similar in those with and without the spot sign, including the baseline ICH volume (p = 0.67), the team reported.

Follow-up CT showed significant ICH expansion (defined as an increase in volume of greater than 30% or 6 mL, calculated using the ABC/2 rule) in 11 patients (28%).

In all, 77% of patients with and 4% without ICH expansion demonstrated the spot sign (p < 0.0001). Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values for hematoma expansion were 91%, 89%, 77%, and 96%, respectively.

"There was an 8.5 times higher risk of hematoma expansion in patients with the sign compared to those who did not have the sign," Aviv told AuntMinnie.com.

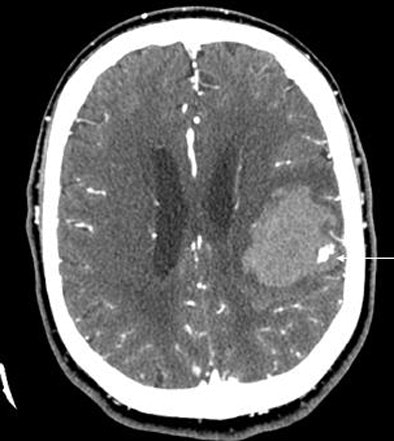

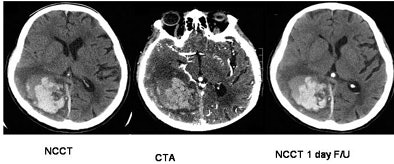

|

| Top, a patient with CTA spot sign (+VE) and hematoma expansion; bottom, a patient with CTA spot sign (-VE) and no expansion. Patients presenting with the spot sign at CT were more than eight times as likely to have hematoma expansion. Images courtesy of Dr. Richard Aviv. |

|

More patients with the spot sign had significant ICH enlargement as well (p = 0.0001). The mean absolute and percentage volume change was greater (p = 0.008), extravasation was more common (p = 0.0005), and median hospital stay was longer (p = 0.04) compared to patients without the spot sign.

Although fewer patients with the sign achieved good outcomes (mRS ≤ 2), this measure fell short of statistical significance (p = 0.16) in the small cohort. The researchers also found no significant difference in hydrocephalus (p = 1.00), surgical intervention (p = 1.00), or mortality (p = 0.60). The spot sign independently predicted hematoma expansion on multivariate analysis (p = 0.0003).

The CTA spot sign, which can be reliably identified by simple visual inspection of CTA source images, is an independent predictor of hematoma expansion, Aviv's group concluded. Contrast extravasation was seen in nearly half of the CTA spot cases, he said.

The preliminary implications for patient management with factor VIIa are clear. "If they do have this sign, they can be treated," Aviv said. "If they don't, they shouldn't."

Further studies are needed to validate the ability of the spot sign to predict clinical outcomes and response to factor VIIa treatment, he added.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

February 26, 2007

Related Reading

Mechanical clot removal can often improve stroke outcomes, February 13, 2007

Advanced MR clarifies nexus between white matter and cerebrovascular disease, February 9, 2007

Relative threshold method correlates CT, MRI stroke infarct assessment, February 9, 2007

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com