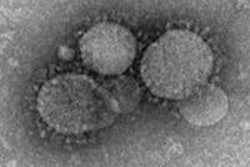

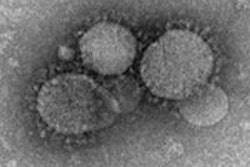

The coronavirus responsible for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in humans is prevalent in camels throughout Saudi Arabia and has been around for at least 20 years, a new study has found.

While most MERS infections have occurred in Saudi Arabia, the origin of the disease in most cases has remained unknown. Efforts to identify an animal source of infection have focused on bats and camels, according to an article in mBio published online February 25.

In this latest study, researchers from the U.S. and Saudi Arabia analyzed blood samples collected from 203 camels across Saudi Arabia in 2013. They found that 150 animals, or 74%, had antibodies to the MERS coronavirus (CoV), indicating past infection.

Nasal swabs and rectal specimens revealed that genetic sequences of MERS-CoV from active infection in camels matched those found in humans. The number of camels with active MERS-CoV infection varied widely by region, ranging from 66% of camels in Taif in the west to none in Gizan in the southwest. Young camels were more than twice as likely as adults to be infected. No evidence of MERS was seen in a similar survey of sheep and goats.

"This study is the first to show that the MERS virus seen in humans is widespread in camels throughout Saudi Arabia," said lead author Abdulaziz Alagaili, PhD, director of the Mammals Research Chair at King Saud University. "This information is crucial for efforts to contain the spread of the disease."

Airborne transmission of the virus between camels seems most likely, based on clues such as the virus being more evident in nasal swabs than rectal specimens. But how humans get the disease has not yet been determined.

MERS-CoV has been carried by camels in Saudi Arabia for more than 20 years, according to the authors. Blood serum samples from camels indicated evidence of the virus dating back to 1992.

"What we know now is that camels carry the same MERS virus that infects humans, which indicates that they have the potential to transmit the virus directly to humans," said study co-author Thomas Briese, PhD, associate director of the Center for Infection and Immunity and associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health.

While the researchers speculated that camels are potential reservoirs for human transmission, the current study does not prove this theory, they noted.

"Our findings suggest that continuous, longer-term surveillance will be necessary to determine the dynamics of virus circulation in dromedary camel populations," they concluded.