"Make a habit of two things -- to help, or at least do no harm."

Hippocrates, The Epidemics

Interventional radiologists strive to follow Hippocrates’ advice in treating patients, but are they doing enough to prevent harm to themselves? Dr. Erik Paulson and colleagues from Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC, took a long look at this question with regard to CT fluoroscopy-guided interventional procedures.

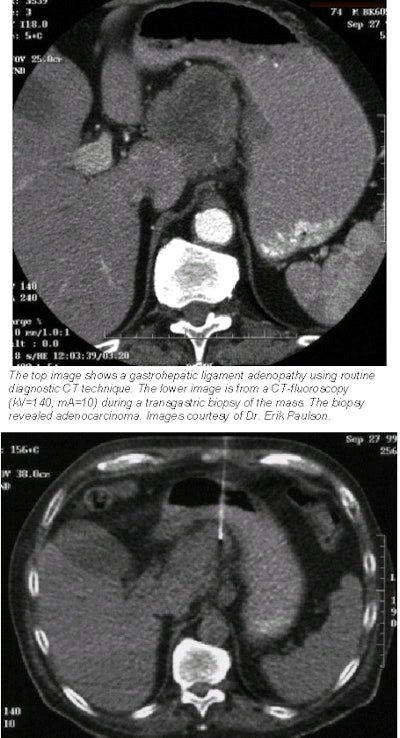

In an article published in this month's Radiology, Paulson and his group studied CT fluoroscopic interventional procedures and measured radiation dose to radiologists. They tested radiation exposure from three CT fluoroscopic techniques: the quick-check technique, continuous CT fluoroscopy, or a combination of these techniques (Radiology, July 2001, Vol.220:1, pp. 161-167).

Real-time radiology

In a previous study, Dr. Richard Nawfel noted that CT fluoroscopy provides physicians with immediate feedback of images during interventional procedures. This is because the images are reconstructed and displayed in real time. However, unlike conventional CT, CT fluoroscopy requires personnel to be in the procedure room while x-ray exposure occurs.

During the procedure, the patient is exposed to radiation at or near the needle puncture site. Exposure to the physician's hands is of great concern, because the hands are closest to the scanning plane during the intervention. In addition, the level of scatter exposure could be high at locations close to the scanning plane during an interventional procedure (Radiology, July 2000, Vol. 216:1, pp. 180-184).

Paulson and his team evaluated 220 CT fluoroscopy-guided interventional procedures performed in 189 patients. The procedures comprised 57 spinal injections, 17 spinal biopsies, 24 chest biopsies, 20 abdominal aspirations, 44 abdominal biopsies, and 58 abdominal drainages. Radiologists performing the procedures wore collar and finger radiation detectors to determine the dose per procedure.

A vast majority of the procedures (87%) used the quick-check technique alone. Four of the procedures (2%) were performed with needle manipulation using continuous CT fluoroscopy, and the remaining 11% used a combination quick-check method and continuous CT fluoroscopy.

Make it quick

The quick-check method requires placing a reference needle using a localizing spiral CT scan as the only guide. The radiologist performs a short CT fluoroscopic exam to locate the needle tip. Spot images are then used to check the needle placement. This technique is also used to confirm the position of a guidewire or a catheter (Radiology, September 1999, Vol.212: 3, pp. 673-681).

The Duke University researchers intentionally set the milliampere value as low as possible, a mean of 13.2 mA, for each procedure.

"Our use of a milliampere value higher than 10 mA was restricted to those procedures in which the target was small or the lesion was subtle, as in some liver lesions," Paulson told AuntMinnie.com.

|

Using the quick-check method shortened CT fluoroscopic times per procedure. Single-section spot images taken during the study averaged 1.2 seconds per exposure. The researchers reported that the mean time on the quick-check method CT fluoroscopic studies was 17.9 seconds.

Most important, the quick-check technique resulted in a very low whole-body radiation dose to the radiologist performing the procedure, with a mean of 2.5 mrem. The researchers noted that individual procedure doses ranged from 0.66 to 4.75 mrem, and that the finger radiation dose was negligible.

"With this dose rate, to exceed a 5,000 mrem body dose per year, a radiologist would have to perform more than 2,000 CT fluoroscopic procedures annually," Paulson said.

Low-dose scatter

The team also measured scattered radiation dose by using a standard anthropomorphic phantom and their most frequently used technical parameters of exposure (140 kV, 10 mA). At a distance of 25 cm from the section, the dose rate was 23 mrem per hour. When measured at 60 cm from the section, the scattered dose rate was 12 mrem per hour.

The scattered dose rate measurements were taken outside the protective lead gown worn by operators in the study. The researchers recommend the use of an appropriate lead apron, thyroid shield, and protective eyewear.

Other suggested safety techniques are stepping away from the gantry when possible, avoiding direct eye contact with the gantry during exposure, and standing at the head side of the table. In addition, putting a lead drape over the patient can reduce scatter radiation.

Using the quick-check method may also reduce the stress on the interventional radiologists' musculature during the exams. According to Paulson, there were no related ergonomic problems reported as a result of performing these procedures.

By Jonathan S. BatchelorAuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 30, 2001

Related Reading

ICRP releases report on pregnancy and radiation, July 17, 2001

AJR review chronicles fluoroscopy-induced skin damage, June 21, 2001

Education and awareness can prevent radiology workplace injuries, May 28, 2001

FDA's radiation concerns may lead to dose displays for scanners, May 22, 2001

New generation of digital fluoro systems can reduce radiation exposure, March 3, 2001

Proposed U.S. rules increase safety and cost of fluoroscopy systems, August 16, 2000

Copyright © 2001 AuntMinnie.com