A pre-Columbian jaguar, a Baule head from the Ivory Coast, a Khmer goddess -- these are just some of interventional radiologist Dr. Marc Ghysels' "patients." In one sense they are ideal: they don't complain, they won't squirm in the CT scanner, and they are unaffected by high radiation levels. On the other hand, they can be frustratingly silent, standoffish, and full of secrets.

For Ghysels, a native of Brussels, Belgium, the challenge is to make his patients -- also known as works of art -- reveal themselves completely, flaws and all. His investigative tool of choice is a CT scanner. Three years ago, Ghysels gave up practicing medicine on humans and devoted himself to art imaging. In 2002, he started a Brussels-based company called Scantix, specializing in the radiological study of fine art and antiques.

At the 2005 RSNA meeting in Chicago, Ghysels and colleagues will offer an educational exhibit on CT of African art. The online presentation will illustrate the spectrum of CT findings, including 3D and 4D, in 250 wooden masterpieces from the Africa Museum in Tervuren, Belgium.

It's no surprise that Ghysels ultimately chose this path. He jokingly described himself as the "black sheep" scientist in a family of artists.

"My father (Jean-Pierre Ghysels) is a sculptor, and both my parents are collectors of ethnographic art, mainly ethnic jewelry," explained Ghysels in an e-mail interview with AuntMinnie.com. "One of my brothers is an art historian and arts publisher."

|

| "Upward Ritual" by Jean-Pierre Ghysels in the lobby of the Hyatt Regency O'Hare in Chicago. Image courtesy of Hyatt Hotels Corp. |

Ghysels earned degrees in medicine, surgery, and obstetrics, as well as diagnostic radiology, from the Free University of Brussels (ULB). He also held fellowships in interventional radiology at ULB and Hammersmith Hospital in London. From 1996 to 2002, he practiced as an interventionalist at the Jules Bordet Institute at ULB and the Edith Cavell Medical Institute, also in Brussels. But he maintained ties with the arts through his family.

"Thanks to that special position, I was able to witness how difficult it was, even for connoisseurs, to properly judge the physical state (recent damage, modern assemblage, restoration) and the authenticity (versus forgeries) of works of art," he stated.

X-ray technology was already being used for authenticating and restoring paintings, but Ghysels had ambitions to take the field one step further. He began by sending his father's sculptures through a CT scanner.

"My father makes clay models of all his new sculptures ... most of the time he had to increase the size of the clay sculpture to a bigger, hammered copper sculpture or bronze (sculpture)," Ghysels explained. "I started to scan his small clay sculptures for fun, then some bigger ones, and even terracotta sculptures."

|

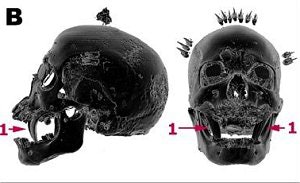

| A 19th century Ekoi head from Nigeria made of bone, teeth, cloth, clay, wood plant fibers, skin, and claws with a height of 26 cm (A). In B, CT surface-shaded display (SSD) views in which the structures of lower density than bone have been erased, revealing that the incisors of a carnivorous animal (1) have been inserted in the upper jaw of a human skull. |

|

Ghysels also began playing with reconstructed CT images, using the Leonardo workstation (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany) and InSpace software (HipGraphics, Baltimore).

Soon Ghysels found art collectors, dealers, and museum curators calling upon him for his CT services. "(They) became so excited seeing how easily and efficiently the CT scanning technique could be applied to clay and terracotta sculptures that they asked me to check other (works)."

|

| In C, a selection of thin axial slices, which illustrates the original technique used to make the head. The nasal cartilage was replaced by a piece of carved wood (2) and covered with antelope skin; the orbits (3) were filled with cloth; the temporal fossae were filled with clay (4) and sticks (5), finely carved to give the impression of scarification. These were inserted under the taut antelope skin. The articulated wooden tongue is attached to the top of the wicker work by a fiber ligature (6). The cavity of the right frontal sinus is filled with a magic charm (7) covered by clay and antelope skin. Images courtesy of Dr. Marc Ghysels. |

Specifically, CT can detect changes in the materials that a sculpture is made of, as well as any damages -- with a resolution of 0.05 mm, the exam can detect the smallest crack or other flaw. Wood objects are the easiest to scan thanks to their low density.

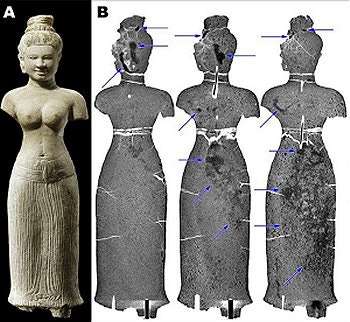

A 3D CT scan that Ghysels did of a 19th century Congolese Hemba ancestor statue (top and front images) revealed that the figure had been carved from different pieces of wood. In addition, the density of the wood and the changes in growth rings proved that the piece had been restored some time after it was created.

Other materials that respond well to CT are ivory, bone, stone, and terracotta. Because clay keeps a trace of every element it has been in contact with over time, a CT scan can reveal the sequence of steps that went into creating the object, as well as ferret out any inconsistencies. This is a vital tool in a field that is littered with fakes (Art Tribal No. 4, Winter 2003, pp. 116-131).

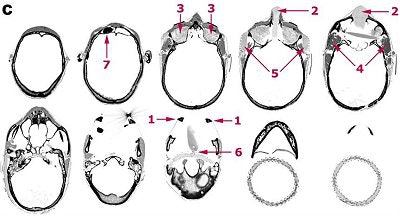

|

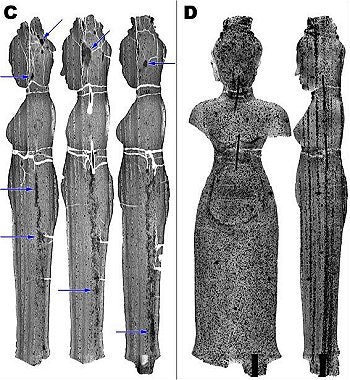

| Sandstone Khmer goddess in Banteay Srei style from Cambodia from the second half of the 10th century with a height of 63 cm. Four thin frontal sections (B) reveal the repair of breaks at the neck and waist with two metal rods sealed with cement in central drill holes. The dark patches are due to resin (arrows) injected into the cracks in a friable rock to ensure better conservation. The horizontal white line represents the border between the CT scans of the upper and lower parts of the statue. |

The kVp that the objects are scanned in ranges from 120-140, which is not enough to scan bronze or other metal. The latter requires a dose range of 225-440 kVp, Ghysels explained. While the CT scan can expose the history of an art object, it cannot be used as a dating technique, he added.

|

| In C and D, five thin lateral sections, which confirm the sedimentary nature of this ferruginous sandstone as the geographical strata of varying density are oriented vertically. The black dots correspond to iron oxide nodules. Despite the breaks at the neck and waist, the continuity of the strata in the three fragments of sandstone glued together proves that the original statue was made from a single piece of stone. These sections also show the areas of injected resin (arrows) and the cracks in the rock, which show up as irregular white lines in the head. |

"The scanner is just a tool to measure the density of the material at the atomic level," he noted. "To the best of my knowledge, there is no measurable relationship between the density of an object and its age, even with humans."

|

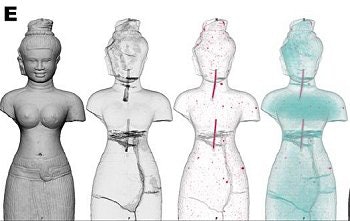

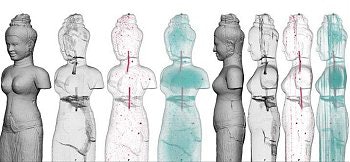

| Frontal and lateral 3D views (E, above and below). The sandstone has been rendered translucent. In the frontal view, apart from the metal rods, the iron oxide nodules seem to be scattered at random. In the lateral view, the sedimentary nature of the rock and the monolithic character of the sculpture are confirmed because this time the nodules are aligned in the geographical strata. Images courtesy of Dr. Marc Ghysels. |

|

Since founding Scantix, the call for Ghysels' services has been brisk. He currently uses Siemens CT scanners in public or private hospitals in Brussels, London, and Hong Kong, during equipment downtime on nights and weekends. He said he hopes to find an available scanner at an institution in New York City as well, especially as demand for his services grows. The price range for having art work scanned, depending on the size, is between $750 and $2,000, according to Ghysels.

"With 'art radiology,' the art work doesn't speak by itself, and most of the time its owner has no idea of the natural history or restoration history of his piece," he stated. "As a radiologist, my goal is to make the piece 'speak' from its internal content, and then to interpret these messages/signs/anomalies ... (and) to decide if they are consistent with the original piece and its natural history over the centuries."

By Shalmali Pal

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

August 25, 2005

To read more of this interview with Dr. Marc Ghysels, and view CT images of forgeries, click here.

Click on the link below to view a video clip of how CT unearthed modern restoration of a Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618-907) terracotta sculpture. The scan showed that metal, glue, and resin were used to assemble terracotta pieces of varying density. The CT exam also indicated that the head had been carved from plaster. The findings indicated that the piece was a modern construction with old materials. Video courtesy of Dr. Marc Ghysels.

Note: In order to play the .wmv file above, you will need to have installed a media player such as Windows Media Player (download) or RealPlayer (download).

Related Reading

CT helps unwrap mummy mystery, March 29, 2005

MDCT solves 400-year-old mystery, November 29, 2004

Radiologist at Louvre trades healthcare for high art, November 1, 2002

Radiography meets flower power in RT's art, July 17, 2001

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com