Some radiologists do their best to avoid CT enterography, but they're missing out on a wide range of diagnoses that alternative exams can't provide.

At the 2007 European Congress of Radiology (ECR) in Vienna, Dr. Patrick Rogalla of Charité Hospital in Berlin offered advice for maximizing the value of CT enterography exams for indications ranging from tumor search to inflammatory bowel disease.

The beauty of multidetector-row CT (MDCT) is that it can often predict the pathology, he said. "The purpose of this talk is to increase your enthusiasm for performing CT enterography -- many people are afraid."

One reason is the size of the small bowel -- anywhere from 2.5 m to 11 m in length, and "it is quite difficult to go through all bowel loops," Rogalla said. The folds gradually decrease in size and frequency with the approach to the terminal ileum, he said.

Multislice CT has brought major improvements to CT enterography, but even with an optimal protocol and the thinnest possible collimation, CT cannot approach the resolution of capsule endoscopy, he added.

To improve the odds of a correct diagnosis, the study protocol should be tailored to the indication for the exam, Rogalla said. The general protocol is probably the best approach for most situations: thin collimation combined with IV and oral contrast. Tweaking the protocol design can yield better results when looking for tumors, inflammation, or suspected ischemia.

Thin slices (1.25 mm or less) are a must, along with a good-sized bolus of contrast material and scan delay of 50-70 seconds. Oral contrast is also recommended for general studies, he said, and involves another choice.

"Iodine and barium suspensions both are currently in use, but there are problems with both of these," Rogalla said. With iodine, for example, it can be difficult to distinguish the bowel from the lumen. The reason is that iodine oral contrast is a little bit heavier than water -- "it settles down if you're not mixing it," he said. And although the taste is pretty bad when correctly mixed with water, it progresses to "horrible" when it settles to the bottom of the glass.

"If a patient drinks a cup of contrast and slowly approaches the bottom, the patient might leave this behind," Rogalla said. Suspiciously enough, he added, "if you have flowers in your radiology department, they always die."

Barium doesn't taste as bad, but it also "settles" in a different way, and the results can be more heterogeneous than iodine, often discontinuous in the small-bowel lumen. But barium may have the edge in revealing unsuspected findings, so both have advantages and disadvantages, he said.

That said, there are patients and indications that make the diagnosis extremely difficult regardless of protocol -- for example, a patient with mild diarrhea.

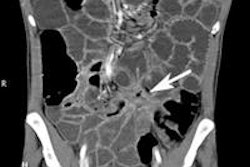

"There is a high threshold for performing CT, but if you do it you might be able to find small changes like ... focal enteritis," due in one example to pathogenic E. coli, Rogalla said.

So-called negative contrast agents such as water and air as well as low-density barium solutions are another possibility because they improve luminal distension, and make some pathology easier to see. But they can also reduce the contrast between the lumen and bowel wall, especially in the absence of IV contrast, he said.

"It might be a problem in some instances if we use negative (oral) contrast agents," Rogalla said. While radiodense contrast agents provide a density difference of 200-300 HU between the bowel wall and lumen, negative contrast agents reduce the difference to about 90 HU, and with noncontrast CT the difference is only about 20 HU.

"A low-density barium solution is little different than water. You might have absolutely no contrast difference on a noncontrast CT -- that's the problem with these solutions that work similarly to water," he said.

Delivery is probably the biggest issue associated with water as a contrast agent. "If the patient is dehydrated, the water may never reach the ileum where the pathology is suspected," Rogalla said. "Nevertheless, some papers suggest that water is perfect for distension of the bowel if you add some other medications to the water, such as mannitol."

Often a bolus of IV contrast combined with a negative oral contrast agent can reveal important pathology, such as hemmorhages, bleeding, and thickening of the bowel wall, that can be obscured by the bright lumen radiodense oral contrast agents produce, he said.

"We use sometimes 250 mL mannitol added to 750 mL water or apple juice," Rogalla said. "One problem is that you need more than one toilet in the department.... All of these preparations produce diarrhea -- that's the biggest disadvantage of (oral) contrast agents."

Radiologists need to be very cautious when injecting liquid in patients with severe luminal obstruction, he noted. When fistula is suspected, a low-density contrast agent may be optimal. No contrast should be given in cases of suspected small-bowel ischemic disease.

For detecting small-bowel neoplasms, the negative predictive value of CT is quite high, surpassing sensitivity of about 80%. "If you don't find anything, and the quality of the study is excellent, you can be quite sure there is no pathology in small bowel," Rogalla said.

Much of the recent research in exam techniques has been driven by PET/CT practice, which requires small-bowel distension to correlate the PET and CT findings, he said. Researchers have gotten good results with some gel-based agents containing ultralow-dose barium.

"The images are OK, but I don't see any advantage over normal water," Rogalla said. "The problem is that it tastes like chewing gum and some people in the department might not like (to drink) 1 liter of chewing gum -- that's the disadvantage."

Still, anything that can distend the small-bowel lumen is helpful, especially when looking for tumors or inflammatory bowel disease in which "we are dependent on distension," Rogalla said. Small-bowel tumors are relatively rare (1:100,000 or 1.5% to 6% of all gastrointestinal neoplasms), but far more likely to be malignant (1:1) than in the large bowel, where the great majority of lesions are benign.

For small-bowel enteroclysis, Rogalla's group begins with duodenal intubation, infusing a mixture of 180 mL of oral contrast media combined with methylcellulose -- a total of 1.6-2 L of contrast. Paraffin should be avoided, he said. IV contrast is also administered. Thin-section CT is performed, with coronal reconstructions.

Some reflux of contrast mixture into the stomach will often occur, and is acceptable as long as it is not enough to induce nausea and vomiting. Reflux into the small bowel is not a problem because large-bowel anatomy can be easily distinguished, he said.

New exam techniques using CT perfusion or combining PET/CT and colonography are proving useful for cancer staging and surgery planning, Rogalla said, citing a 2006 study of colon cancer patients that compared TNM staging with CT, PET/CT, and PET/CT colonography (Journal of the American Medical Association, December 6, 2006 Vol. 296:21, pp. 2590-2600).

PET/CT colonography had a slight edge, the results showed. The overall TNM stage was correctly determined for 37 lesions (74%) with PET/CT colonography, 32 lesions (64%) with CT plus PET, and 26 lesions (64%) with CT alone, using a 7-mm node threshold. Surprisingly, no difference was seen between PET/CT colonography and CT alone in N staging, but overall staging results were 22% better than CT alone, Rogalla said.

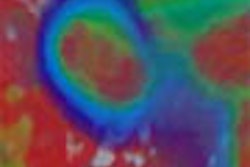

Another study, by Goh et al in the U.K., that found CT perfusion could effectively distinguish between colorectal cancer and diverticulitis, outperforming morphological assessment (Radiology, February 2007, Vol. 242:2, pp. 456-462).

In 20 patients with colorectal cancer and 20 with diverticulitis, mean blood volume, blood flow, transit time, and permeability were significantly different between the groups (p < 0.0001). Cancer patients had the highest blood volume, blood flow, and permeability, as well as the shortest transit time. Blood volume and blood flow each had a sensitivity of 80% and had specificity of 70% and 75%, respectively, for cancer in comparison with standard morphologic criteria, the researchers found. Baseline values were predictive as well: Patients with high blood flow and short transit time responded poorly to treatment.

The mucosa is highly vascularized, and this feature can be used to aid diagnosis, Rogalla said. In 2005, Sahani et al used first-pass perfusion CT to examine tumor vascularity in rectal cancer and determine whether any of the perfusion parameters would predict tumor response to chemotherapy and radiation therapy (Radiology, March 2005, Vol. 234:3, pp. 785-792).

The researchers performed perfusion CT in 15 patients with rectal cancer and five prostate cancer patients who served as controls. In nine patients, perfusion CT was repeated after completion of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

Rectal cancer had higher blood flow and shorter mean transit times compared with those of normal rectum (p ≤ 0.05), the group reported. After treatment, tumors showed significant reduction in blood flow and increase in mean transit time compared to baseline, and there was a significant difference in baseline blood flow and mean transit time values between responders and nonresponders (p ≤ 0.05).

"If you're doing a focused study for tumor search and inflammatory bowel disease, CT enteroclysis is the way to go," Rogalla said. You will probably want to use radiodense contrast to search for small tumors that "may not enhance more than the bowel wall, and can be extremely difficult to see in the context of small-bowel loops," he said. "But if the distinction between perfusion and the bowel lumen is the target, I would go for negative contrast agents, for instance in the situation of small-bowel infection and inflammatory bowel disease. Overall, MDCT improves sensitivity in ischemic disease, and if you are still performing small-bowel conventional studies, there is something you can do (with CT) beautifully."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

May 22, 2007

Related Reading

Capsule endoscopy accurately identifies obscure GI bleeds, May 3, 2007

Capsule endoscopy readily spots obscure GI bleeding, April 16, 2007

3D reveals what axial images can't in small-bowel CT, November 15, 2007

CT enterography can determine Crohn's disease severity, November 7, 2006

Success begets growing role for CT enteroclysis, November 18, 2004

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com