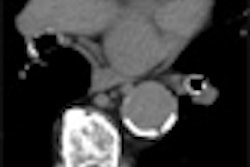

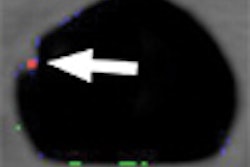

More likely than not, a patient with unexplained shortness of breath or other symptom suggestive of pulmonary embolism (PE) will be sent for CT pulmonary angiography (CTPA) to rule it out. CT is fast and it does the job when vessels are examined systematically, but its false-positive rate can be high when combined with a low clinical probability of PE.

On the other hand, alternatives such as ventilation/perfusion (V/Q) scintigraphy can be complicated to perform and are often inconclusive. A negative D-dimer test is sensitive but not specific, though the negative predictive value is high when combined with a low clinical probability.

Is the use of CTA too automatic, serving up superfluous radiation in exchange for too many negative results? And if CTA is negative, should other tests be used systematically to find the cause of the patient's symptoms?

Poster presentations at the recent 2007 American Thoracic Society (ATS) meeting in San Francisco shed new light on the use of CT in cases of suspected PE. One group found that its positive rate for PE was too low at CTA, and has incorporated the Wells clinical criteria into its referral software to ensure the scans were needed. A second group looked further into negative CT results and found lots of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A third group found that whatever the diagnosis, CT was so helpful in finding the problem that it was worth keeping as a first-line test.

Pulmonologist Dr. William Bulman and colleagues at Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City wanted to find out if CT was being applied too frequently, based on the positive rate.

"There was a general perception on the part of physicians at my hospital ... that we were ordering too many CTAs, particularly in patients that didn't need it, where the indication for PE was very low and where nonradiological testing could essentially rule it out," he told AuntMinnie.com. "We know there are Wells (clinical probability) criteria, but for the most part they don't implement it."

In any case, it is difficult to examine clinical criteria retrospectively, since they rely so heavily on the treating clinician's impressions of the patient, Bulman said. So the study counted the number of CTA exams ordered to rule out PE, how many of the exams were positive, and used the positive CTPA rate "as a general surrogate marker for where we stood compared to other institutions, something we could track over time if we implemented programs to exclude unnecessary studies," Bulman said.

So far only the first part has been completed, but the results are instructive. CTPA was performed in 186 patients (68% women) in the three-month period. Two were nondiagnostic, while 158 were negative for PE. In all, 26 studies were positive for either PE or deep vein thrombosis (DVT), for an overall positive rate of 14%.

While two of four outpatient studies were positive, only 13% of emergency department studies and 13% of inpatient studies, which were presumably more selective, were positive for PE. Only two-thirds of the patients were getting D-dimer studies.

"We plan to impose the Wells clinical criteria based on order entry," Bulman said. "Now when physician goes to order CTA, we'll have a little screen pop up giving them a clinical algorithm and suggesting that they use it, explaining to them that there is literature to support the fact that low Wells criteria probability combined with a negative D-dimer (< 2) means a low probability for PE," he said. And if both of those things are true, do you still want to order CTA?

A large multicenter trial in the Journal of the American Medical Association last year of more than 1,000 patients with a negative D-dimer and low clinical probability of PE yielded only a 0.5% rate of venous thromboembolism in the three-month follow-up, the same rate as a negative CTPA study (JAMA, January 11, 2006, Vol. 295:2, pp. 172-179).

The best studies that accounted for clinical criteria, such as the Prospective Investigation of Pulmonary Embolism Diagnosis (PIOPED) III trial, yielded about a 23% positive rate for CTPA. "Anything higher than that and you're probably missing some PE," Bulman said.

What negative patients have

Dr. Johanna Kwakkel-van Erp and her colleagues from Reinstate Hospital Arnhem in the Netherlands participated in the 2006 JAMA study and examined the patients further in a new study of those in whom PE was ruled out. The latest study applied the so-called Christopher strategy (simplified Wells clinical decision rule combined with D-dimer or CTPA) to 163 patients in whom PE had been ruled out.

"We were interested in all patients suspected of PE but in whom no diagnosis was found," Kwakkel-van Erp told AuntMinnie.com. "The diagnostic workup of patients with PE is mainly focused on excluding PE rather than confirming a diagnosis."

CT confirmed PE in 45 patients, who were excluded from the analysis, along with 13 patients with a history of asthma or COPD. In the remaining 93 patients, the researchers performed spirometry and a histamine provocation test, finding COPD or asthma in 26 patients (25%). By extending the Christopher strategy with lung function tests, more symptoms could be explained, Kwakkel-van Erp said.

"Probably instead of only excluding one diagnosis, we should also look for an alternative diagnosis," particularly obstructive lung disease, Kwakkel-van Erp said; too often a PE rule-out ends the search for a diagnosis. The group plans to continue following up its large database of more than 5,000 patients.

Finally, Dr. Aref Agheli and his colleagues from Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center in New York City, retrospectively analyzed the frequency of incidental findings at CTPA to assess the usefulness of the study in determining the eventual diagnosis. They also reviewed CTA and chest radiography findings to evaluate their total contribution to the incidental findings.

According to the results, CTA confirmed PE in 24.3% (33/136) patients. CTA identified at least one finding in 92.2% (95/103) of the patients without PE, of which 71% required immediate intervention. The findings included pleural effusion (n = 38) not identified at radiography. Cardiomegaly or pericardial effusion was seen in 42 patients, atelectasis in 37, infiltration in 33, enlarged intrathoracic lymph nodes in 31, COPD changes in 27, unsuspected mass in 19, interstitial lung disease in 10, and other pathologies in 12. In 68% of the cases that also had chest x-ray, the additional findings could not be detected.

Chest x-ray and V/Q too often miss pertinent findings, and CTA is very valuable for establishing the diagnosis in these patients, Agheli said.

"Even if a patient comes in with symptoms of PE, and you do the CTA and you don't find PE, you will have another finding in that scan that's going to contribute to the diagnosis, including pneumonia, malignancy, pleural effusion or cardiovascular findings, lymphadenopathy, COPD changes, and many other important things -- especially malignancy," he said. "That's why we encourage the physicians to do CTA more often in patients who are symptomatic."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

July 16, 2007

Related Reading

CAD shows promise in tumor detection with PET, June 5, 2007

Duke researchers combine DR tomosynthesis with 3D CAD, June 4, 2007

Divergent research on CT lung screening sparks more debate, fewer answers, April 19, 2007

Pulmonary embolism an uncommon cause of COPD flare, March 16, 2007

CAD turns in mixed performance for pulmonary embolism, January 16, 2007

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com