Folks who arrive at the emergency department (ED) with chest pain have a lot of company -- nearly 6 million patients a year in the U.S. alone find themselves in such dire circumstances.

Diagnosing and triaging all those patients remains a major clinical challenge for doctors, and the cost of care is high, though less costly than a lawsuit should the wrong patient be sent home.

The immediate aim is to separate acute chest pain patients with acute coronary syndrome (transmural or subendocardial myocardial infarction [MI], unstable angina) from those with other cardiac and noncardiac causes.

Can CT reliably exclude acute coronary syndrome? A trove of mostly single-center studies says it can. While myocardial perfusion SPECT has been the mainstay imaging modality for chest pain patients, multidetector-row CT's impressive accuracy, especially its high negative predictive value (NPV), is starting to change protocols at emergent care facilities.

When used appropriately, dedicated ECG-gated coronary CT angiography (CTA) can rule out coronary artery disease in chest pain patients and send them on their way. If necessary, aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism can be ruled out at the same time with triple rule-out CTA that extends the anatomic coverage and tweaks the contrast recipe.

But who should get scanned, and how should the results be applied? At the 2008 International Symposium on Multidetector-Row CT in San Francisco, Dr. William Shuman, professor and vice chair of radiology at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, discussed his institution's evolving protocol for assessing risk and sorting out chest pain patients with CT. As it is, mistakes are rare but costly, he said.

"Out of 5 million patients, only 15% actually have MI, 10% are sent home in error, with 2% to 5% mortality at home" Shuman said. "More important for practices is that 20% to 40% of medicolegal liability for ED physicians arises from the small number of patients who are sent home with an MI. So that's why [hospitals] are very nervous about this population, why they tend to be quite cautious with them, and maybe overadmit them. Sixty percent of chest pain patients are admitted for 24 to 48 hours for observation, and this runs up a lot of costs."

At the University of Washington (UW) Medical Center, the current standard of care is serial cardiac enzymes at six, 12, and 24 hours after onset of pain; serial ECG exams for the first 24 to 48 hours; and echocardiography or radionuclide stress test, he said.

But tests aren't all. When evaluating MI risk, distinguishing risk factors from clinical suspicion index is important, Shuman said. The classic Framingham risk score includes hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, obesity, diabetes, and family history of early coronary artery disease, as well as age and sex. On that basis, Framingham's 10-year risk is stratified into low, medium, and high.

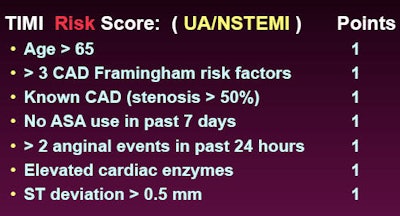

Another tool, the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) risk score for unstable angina and non-ST elevation MI, aims to predict the risk of death and ischemic events among patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. Having more than three Framingham risk factors counts as one point with the TIMI score. Having known coronary artery disease with stenosis of 50% or greater adds another, as do elevated enzymes and ST deviations greater than 0.5 mm. The risk of major cardiac events rises in a very linear fashion when the TIMI score goes up, Shuman said.

|

| TIMI risk score is designed to predict the risk of death and ischemic events among patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome. All images courtesy of Dr. William Shuman. |

|

On the other hand, "when ER physicians talk about clinical suspicion, they mean they've done a clinical history of the patient, they've done ECG and enzymes," he said. High clinical suspicion means significant ST change of 2 mm or greater, positive cardiac enzymes, and/or typical pain. These patients are excluded from CT and sent to the cath lab.

Moderate clinical suspicion is defined as ST segmental elevation or depression less than 2 mm, negative cardiac enzymes, or atypical pain, and these moderate-risk patients are also eligible for gated CT, Shuman said. A low clinical suspicion is defined as no ECG changes, negative enzymes, and noncardiac chest pain; these patients are also eligible for CT.

Thus, for gated CTA eligibility, "we exclude high-risk or high clinical suspicion, and we consider low or moderate risk or clinical suspicion," he said.

For suspected pulmonary embolism (PE) and the question of whether to use a triple rule-out scan to find PE, the D-dimer test is the great separator, Shuman said. If D-dimer results are less than 1.2 mg/L, the negative predictive value for PE is close to 100%. If D-dimer is greater than 1.2 mg/L, 8% of patients will have PE.

Evaluating the clinical criteria for suspicion of aortic dissection can be done in a similar manner, Shuman said. For dissection, atypical pain means low suspicion, typical pain means moderate risk, and typical pain plus marfanoid body habitus or hypertension means high risk.

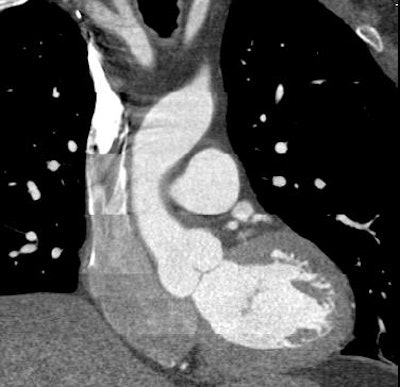

Finally, a grid comprised of the risk assessment for each condition can be created to determine if coronary CTA or a triple rule-out scan is needed, he said. In the multirule-out approach, the aim is to opacify all three arterial beds simultaneously.

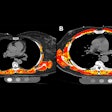

|

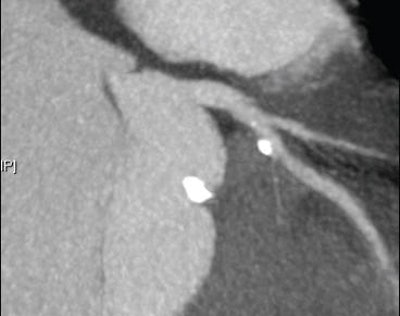

| Top, triple or multirule-out CTA in a patient with atypical pain but normal arteries shows good opacification in all three arterial beds (coronary, pulmonary, aorta). Below, CTA of a low-risk patient with chest pain shows typical "vulnerable plaque" with little stenosis and positive remodeling. Bottom, triple rule-out scan in a patient presenting with atypical chest pain reveals aortic dissection. |

|

|

CT's NPV for ruling out pulmonary embolism is 96% to 99%; for aortic dissection NPV was 99.7% in a study of 373 patients by Hayter et al, Shuman said (Radiology, March 2006, Vol. 238:3, pp. 841-852).

As for CTA's sensitivity for acute coronary syndrome, Gallagher and colleagues scanned 92 low-risk chest pain patients admitted to the ED, who were examined with rest/stress sestamibi myocardial perfusion and 64-detector-row gated coronary CTA. For detecting acute coronary syndrome or major cardiac events within 30 days, CT held the edge in both sensitivity and specificity at 86% and 99%, respectively, versus 71% sensitivity and 97% specificity for rest/stress perfusion. CT was at least as accurate as the stress test in these patients with chest pain, the group concluded (Annals of Emergency Medicine, February 2007, Vol. 49:2, pp. 125-136).

In another study, Hoffman et al examined 103 ED patients with CTA, blinded to the clinical results, following the cohort for five months. CTA's sensitivity, specificity, and NPV for predicting acute coronary syndrome were 100% (Circulation, November 21, 2006, Vol. 114:21, pp. 2251-260). In dozens of published studies, the NPV of MDCT for acute coronary syndrome has remained close to 100%.

And the NPV is high for two other entities: aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism, Shuman said. But what about the chest pain patient with negative enzymes, normal ECG at admission, and a completely negative CT scan? Can they be safely discharged?

Yes, they can, concluded Goldstein and colleagues, whose study randomized 197 chest pain patients to CTA (n = 99) or nuclide stress tests (n = 98). Patients with minimal disease at CT were discharged. Patients with stenosis greater than 70% at CT were sent for catheterization, and those with intermediate lesions or nondiagnostic scans underwent stress testing.

The results showed that CT alone could exclude or identify coronary disease as the source of pain in 75% of the patients, with the remaining 25% sent for stress testing due to inadequate image quality (cited as a limitation of CT) or intermediate-sized lesions, Goldstein and colleagues wrote. CT also shortened diagnostic times by 12 hours and reduced the financial burden of the workup significantly ($1,586 for CT versus $1,872 dollars for standard of care, p < 0.001), while generating fewer repeat evaluations for recurrent pain (two CT patients versus seven for standard of care).

No patient sent home after negative CT had an adverse outcome (Journal of the American College of Cardiology, February 2007, Vol. 49:8, pp. 863-871).

In addition to being safe, Savino and colleagues from Italy found CTA to be cheaper. Shuman cited their study of 46 chest pain patients, half of whom were sent to CT and half to catheter angiography as a control group. The CT and angiography approaches cost $11,800 and $20,300, respectively, saving 42%.

"If we took that study to the U.S. and applied it to the chest pain population in the ED, we'd be talking about $12 billion a year in savings," Shuman said.

Other CT limitations

Other CT limitations are diminishing, Shuman said. Nonevaluable segments due to noise, motion, or calcifications aren't a significant problem when CT is performed adequately, just 1% to 2% at UW, he said. And dose is far less serious a concern with prospective gating.

"Right now we're doing almost all our triple rules-outs with prospective gating, and operating in the 4 to 9 mSv dose range," he said. The image quality is nearly identical to that of retrospectively gated studies, though functional imaging isn't possible.

The ED nurses at the University of Washington Medical Center keep plenty of oral metoprolol on hand so the patients can be prepared quickly for scanning, he said.

Finally, to compensate for reader variability, chest pain patients are admitted and observed with stenosis of 30% to 70% rather than 50% and greater.

But will ED physicians act on the negative CT results? There is bound to be resistance when the idea is proposed, Shuman said. He advises ED physicians to look at CT as simply another data point in their overall judgment of the patient.

"After a while, they began to sort of send some patients home earlier who had a negative CT and negative enzymes," he said. "Sometimes they would wait for the second set of negative enzymes and a second ECG before they did that. But now we're starting to see them send home patients who are entirely negative from the low and moderate suspicion group at the four- to six-hour time frame. And I think we're going to see that kind of practice start holding out in more areas as we move forward."

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

August 22, 2008

Related Reading

Prospective gating minimizes dose in 320-slice CTA, August 5, 2008

Fourth-generation MDCT scanners do cardiac differently, July 8, 2008

CARS report: Fuzzy theory yields sharper CTA images, June 27, 2008

Using coronary CTA first versus SPECT cuts costs, May 30, 2008

Low-dose coronary CTA diagnoses most patients, November 28, 2007

Copyright © 2008 AuntMinnie.com