How many virtual colonoscopy cases does a trainee have to read before becoming proficient? On average, 164, say Dutch researchers who took a stab at the enduring question in the February issue of Radiology.

Of course, individual performance varied and a few trainees fell short of the mark, but in their new study Marjolein Liedenbaum, MD, and colleagues found that individuals with widely divergent backgrounds could reliably attain high diagnostic performance levels after adequate training.

Previous research has shown that cancer and polyp detection in virtual colonoscopy (also known as CT colonography or CTC) improves with practice, but there is no consensus about how to achieve the desired level of accuracy, and several different kinds of programs have been developed to achieve it, according to the researchers from Academic Medical Center Amsterdam and Erasmus MC University Medical Center in Rotterdam.

Training methods "include reading colonoscopically verified CT colonographic images, peer-reviewed reading of CT colonograms, and a course with presentations of CT colonographic examination results and instructions on the use of CT colonography software," they wrote. "From these previous studies, it appears that CT colonography is a hard technique to learn. However, it has been shown that medical students and technicians are capable of learning CT colonography and achieving diagnostic performance equal to that of radiologists" (Radiology, February 2011, Vol. 258:2, pp. 477-487).

There are also many kinds of errors to train against, including errors of search, where the radiologist's gaze misses the abnormality; errors of detection, where the radiologist's eyes pass over the detection but fail to recognize it; and errors of decision, where radiologists incorrectly characterize an abnormality they have recognized.

Errors of search and detection "might be decreased when a set of examples of true- and false-positive findings is provided to a radiologist for training," Liedenbaum and colleagues wrote. "To reduce those errors in an efficient manner, a formative training program should be followed. One previous study on CT colonography training used an extensive formative training that comprised lecture sessions, pitfalls training, and a training set of 60 CT colonographic examinations with unblinding after each case."

The Reston, VA-based American College of Radiology's (ACR) certification program recommends training on anatomy, pitfalls, pathogenesis of colorectal cancer, and examination technique, in addition to 50 to 75 endoscopically validated CTC cases. However, "to this date, no study has tried to estimate the number of CT colonographic acquisitions to be evaluated by radiologists, radiology residents, and technicians to reach a sufficient level of competence," the authors wrote. Toward that end, the study aimed to find the optimal number of CTC cases required for competency.

In the study, testing relied on 200 endoscopically confirmed CTC cases from a research database, including 100 CTC exams with at least one polyp 6 mm or larger. Following a lecture and brief, individual, hands-on training, CTC training for the nine readers was performed individually with immediate feedback of colonoscopy outcome. Sensitivity was calculated per polyp for each of four sets of 50 CTC examinations for lesions 6 mm or larger. The number of exams needed to reach 90% sensitivity for lesions 6 mm or larger was estimated and reading times were recorded.

For all cases, CTC was performed prone and supine in the standard manner following automatic insufflation of CO2 (ProtoCO2l, Bracco Diagnostics, Princeton, NJ). Low-dose scanning protocols were used on two 64-detector-row CT scanners.

All images used in the study had been prospectively interpreted by two of seven experienced observers. In all cases, the more experienced observer of the two had read at least 350 CTC studies with colonoscopic verification. Observers had marked all polyps and indicated morphology, size, and location. All CTC studies of insufficient quality due to insufficient distention or inhomogeneous tagging of feces as judged by the experienced readers were excluded.

The results showed that the estimated number of CTC examinations for a sufficient sensitivity was 164, while novice readers can reach sensitivity equal to that of an experienced reader after practicing with 175 training CTC studies. The levels apply to a reading protocol with a lesion prevalence of 50% of CTC studies with at least one lesion 6 mm or larger.

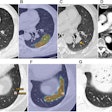

CTC sensitivity by exam training volume

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Sensitivity increased along with increasing reader experience for all polyp sizes. |

A significant difference in sensitivity was found between the first and second set of 50 CT colonographic examinations (p = 0.034) but not between later sets (second versus third, p = 0.74; third versus fourth, p = 0.76).

Three readers in the study, including two technologists and one radiology research fellow, did not achieve sufficient sensitivity and probably need additional training. But background did not dictate post-training performance. Two of the three technologists didn't achieve the desired sensitivity level.

Previous studies recommended that proficiency in virtual colonoscopy could be achieved at levels between five and 100 cases, but the sensitivity of the novices did not reach that of experienced readers. The ACR, American Gastroenterological Association Institute, and International Collaboration for CT Colonography Standards recommend dedicated training for CTC that includes 50 to 75 endoscopically validated CTC cases that are interpreted during an intensive training program with direct tutor feedback, the authors wrote.

"This is a more labor-intensive method than we used in our study," according to Liedenbaum and colleagues. "Furthermore, the requirement of 75 training cases has never been proved to be sufficient. We chose to keep the introductory didactic period short and let readers train alone, while having a tutor available to answer questions that might arise. In this way, direct trainee-tutor interaction might occur at moments that are most helpful to the novice reader while being less labor intensive for the tutor."

Smaller lesions (6-9 mm) were more difficult to detect, the authors noted. Significant increases in sensitivity for detecting lesions 6 mm or larger were seen only after 150 CTC exams. For lesions 10 mm and larger, performance improved substantially between 50 and 100 cases.

"This suggests that smaller lesions are less conspicuous, and readers need more perceptual learning to reduce the errors of search and detection," the authors wrote. Reading times decreased with learning, especially after the first 50 CTC examinations, which is consistent with earlier studies.

Some aspects of training remain unclear, such as the optimal percentage of positive cases. The authors used CTC exams with a 50% disease prevalence, optimal for calculating both sensitivity and specificity. However, "an enriched training set with a higher number of lesions might result in a steeper learning curve for sensitivity," they wrote, noting that Dachman and colleagues used a training set consisting of 83% abnormal results. As for study limitations, only one of the trainees was an abdominal radiologist, and the number of readers was limited.

"We found that CT colonography interpretation can be adequately performed after a computer training program by inexperienced radiologists, radiology fellows, and radiology technicians," they concluded.

An average of 164 VC exams with colonoscopic verification was needed in a specific training setting to reach the sensitivity level of an experienced reader. In all, six of nine readers reached the level of sufficient competence within 175 training CTC examinations with a lesion prevalence of about 50% for lesions 6 mm or larger.

"A few readers did not reach this level after 200 CT colonographic examinations and might need more training or might not be able to reach this level at all," they wrote.

By Eric Barnes

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

February 4, 2011

Copyright © 2011 AuntMinnie.com