The use of computer-aided detection (CAD) always improves reader sensitivity in virtual colonoscopy datasets, say researchers from the University of Pisa in Italy, who reviewed the literature and found that CAD significantly improved detection of polypoid lesions across the board.

On the other hand, CAD increases reading time modestly, delivers poor sensitivity for detecting nonpolypoid colonic lesions, cuts specificity a little, and increases the rate of false positives. But these drawbacks do not outweigh the technology's benefit in improving sensitivity.

"These tools are often used for screening purposes, so we are more interested in not missing lesions than in having one more false positive that is discarded by the human reader," said Dr. Lorenzo Faggioni from the University of Pisa. "The goal is to have human readers not miss potential lesions."

In a talk at the 2011 Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery (CARS) meeting in Berlin, Faggioni said that CAD fills in where both the image data and the reader fail, and there are several reasons why it's needed.

Virtual colonoscopy (also known as CT colonography or CTC) consists of a large number of images to be read -- at least 1,000 per dataset using 64-detector-row CT, he said -- and that's a lot of data for human readers to review.

The image data, usually acquired for screening purposes, use the lowest possible radiation dose, increasing image noise and reducing image quality.

A large caseload can induce reader fatigue and negatively affect the radiologist's performance. The lack of a systematic search method also leads to missed lesions. Some lesions may be discarded by the radiologist because they don't look pathological.

"CAD for CTC allows us to identify pathologies on the colonic wall," he said. "By applying dedicated algorithms to image analysis, CAD allows us to highlight lesions based on irregularities of the surface or the curvature and highlight them as potential candidates," Faggioni said. "[The systems] actually help us see by analysis of the surface, curvature, density, and shape, and allow us to detect polyps by saying 'look at this and find out if it's a polyp.' "

CAD systems are, of course, composed of several different applications that provide for polyp detection, segmentation to distinguish the colon from surrounding organs, and identification of regions of interest that highlight potentially abnormal areas, he said.

Feature extraction surveys different polyp features, while the most critical component is classification, in which the algorithm finally distinguishes normal from abnormal regions. The CAD output is literally a list that asks the reader to decide whether each detection is a real polyp or an error, Faggioni said.

A good CAD algorithm must distinguish reasonably well between normal and abnormal abdominal findings and classify findings with high sensitivity, he said. Some CAD schemes allow the user to select between higher specificity, i.e., fewer false positives, and better detection sensitivity, with more false-positive findings.

In their study, Faggioni and colleagues aimed to examine the performance of CAD versus no CAD in peer-reviewed studies. They performed a literature search of studies that compared findings with and without CAD, and they also determined if CAD produced a net gain or loss in sensitivity, and whether the difference was significant, he said.

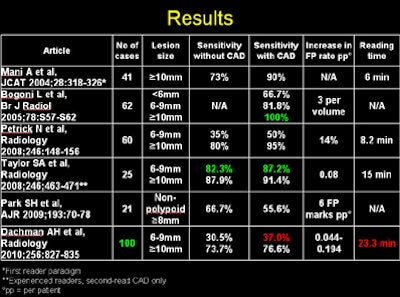

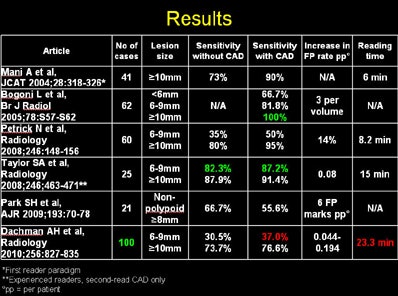

The studies ran from a paper by Mani et al in 2004 to a study by Dachman et al in 2010 and encompassed a wide range of lesion sizes, but most CAD detections were in the medium-sized, 6- to 9-mm lesion range, up to about 1 cm, Faggioni said. A 2009 study by Park et al found nonpolypoid lesions up to about 8 mm.

"In most cases, sensitivity was statistically significantly better with CAD," according to Faggioni:

- The average sensitivity gain before and after CAD was approximately 15%.

- The average specificity fell by roughly 10% with the use of CAD.

- Overall reading time increased by six to 15 minutes using CAD.

|

| Image and data courtesy of Dr. Lorenzo Faggioni. |

"This [increase in reading time] is reasonable if we consider the overall gain in sensitivity, with reasonable worsening in specificity," he said.

The reading time outlier was the Dachman et al paper, reporting 23 minutes of additional reading time; however, the study of more than 100 cases demonstrated an overall improvement in reader performance and a small reduction in sensitivity, Faggioni said.

"In all cases, we also had an increase in false-positive findings with CAD, and we found an increase in reading time," he said.

Of note, according to Faggioni, Dachman et al concluded that their larger study of 100 patients led to a significant improvement in overall reader performance. Petrik et al in their 2008 study noted that CAD boosted sensitivity significantly, with a small decrease in specificity.

A small dip in overall specificity is inevitable, Faggioni said, considering that the detection algorithm is looking at the shape and curvature of the colonic wall, and sometimes normal colonic tissue will meet the criteria and trigger a CAD mark.

"It's up to the reader to decide if it's real or not," he said, adding that it doesn't appear that larger numbers of false-positive marks detract from reader performance.

Taylor et al found different performance levels depending on reader experience, with experienced readers outperforming those who had just undergone training.

"The training course is better than nothing -- it's one of the most important tools for learning CTC -- but it can't replace experience in the field with many exams read in practice," he said. The experienced reader knows what to look for, and he or she knows when to consider a finding to be potentially a real polyp worthy of additional scrutiny.

"The problem is that CAD is less sensitive for nonpolypoid lesions," he said. "When we have flat lesions or large nonpolypoid lesions, the sensitivity of CAD is lower, but the sensitivity of the human reader is also lower," he said.

Still, in Park et al, "the difference between the human view and CAD, even when both were wrong, was not significantly different," Faggioni said. And both human readers and CAD delivered higher sensitivity for adenomatous lesions over nonadenomatous lesions (p = 0.014 and p = 0.046, respectively), and for adenocarcinomas over noncancerous lesions (p = 0.003 and p = 0.0001, respectively), demonstrating that more significant findings are likelier to be detected.

As for false positives, Dr. Luca Bogoni, who developed a CAD system, looked at 150 patients with polyps 6 mm or larger and reported sensitivity averaging 90%, and just three false positives per dataset.

Compared with CAD-unassisted reading, the use of CAD leads to increased sensitivity for detecting polypoid lesions, Faggioni said, and the increase in false positives is usually limited. Total reporting time is reasonable and not substantially influenced by the use of different CAD tools.

"CAD should not be used as a standalone" application, he said. "It should support the radiologist and also be used by experienced readers." CAD can and should be used as a teaching tool for novices, he added.