Now that a major study has shown that lung cancer screening reduces mortality, healthcare payors want to find out if it's cost-effective -- and they'll soon know the answer, according to a presentation at last week's American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN) fall meeting in Arlington, VA.

Dr. William Black, professor of radiology and family practice medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, said his group is completing a cost-effectiveness study based on data from the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) (New England Journal of Medicine, August 4, 2011, Vol. 365:26, pp. 395-409).

"Once something works, you have to try to figure out if it's worth it -- what's the biggest bang for the buck," Black said in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "In today's climate of limited resources, it's important to look at the cost-effectiveness of what we're proposing to do," which is screen smokers and former smokers with CT to try to catch lung cancers at an earlier, curable stage, he said. "It was part of the original plan" with the NLST because "we knew it would be a huge issue at the end of the day."

Simply put, screening is not going to occur unless the cost of each additional quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained is reasonable, he said. In the U.S., the informal dividing line between cost-effective and not cost-effective is somewhere around $50,000 spent per QALY.

The NLST examined more than 53,000 smokers and former smokers and found a 20% reduction in mortality among those who underwent CT screening to detect lung cancer, compared with those who received digital radiography-based screening. However, neither private payors nor the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has indicated a willingness to cover the cost of screening and follow-up of smokers, Black said.

For its part, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) calls the NLST data inadequate for making a decision, he said, and the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), which examines the health impact of cancer screening on the population, is also studying the issue.

While Black discussed his cost-effectiveness study at the ACRIN meeting, he refrained from presenting results, as data analysis is still in progress. "We're still getting the dataset cleaned before we can do the analysis," he said.

'Back-of-the-envelope' estimate

Black said they created a "back-of-the-envelope" estimate in June for the National Cancer Advisory Board, but he emphasized that those estimates were not based strictly on NLST data but rather his own, reasonable estimates of what occurs in lung screening practice, he told AuntMinnie.com.

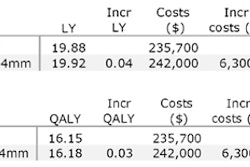

Based on the rough estimates, 39.1% of patients screened would have a positive finding, e.g., a nodule 4 mm or larger, and each patient who was positive at baseline screening would undergo two follow-up chest CTs based on current practice standards. A 20% mortality reduction would work out to about a 0.04 increase in life-years when divided across the NLST cohort, he said.

As a result, the cost of diagnosing, following, and treating the earlier cancers in screened patients will be roughly equal to the cost of not screening, which will reveal fewer but more advanced cancers requiring more expensive care including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, and the like, Black said. And if screening or not screening is a wash in terms of the cost of care, the cost of screening and follow-up alone would represent the additional cost if the decision were made to screen.

That would amount to three CT scans per positive patient ($1,200), and much less frequently the cost of biopsy and surgery ($320 per patient) -- since only about 3% of screening patients end up getting an invasive procedure, he said -- for a total of $1,520 per patient.

If this holds true, the additional cost of screening would work out to about $38,000 per QALY, a cost that is certainly reasonable, he said. Should this estimate hold up to the NLST data, lung cancer screening "would be a great deal" economically, Black said.

Of course, he cautioned, "it's a huge assumption that the overall cost of treatment would be the same in the two [screening and nonscreening] arms," Black said. "We will definitely have to confirm it. I reasoned that on the CT screening side we'd have more surgery because we would find more earlier lung cancers [compared to] fewer more advanced cancers requiring chemotherapy and radiation" on the nonscreening side. "I think it's going to be a very close call," he said.

And even if similarly low costs should pan out from the NLST data, "no one is going to assume that's what you would have if you were to open up screening to the community," he said. "To maintain that very cost-effective approach, you would need really strict limits on screening based on smoking history and how you interpret CT scans, what you do with positive findings, and how you manage patients in terms of treatment."

Also, deaths from lung cancer surgery in the NLST trial were only about 1%, but in the general population it can be as high as 4%, he said.

Finally, Black acknowledged that another recent study, a model-based analysis by McMahon et al (Radiology, July 2008, Vol. 248:1, pp. 278-287), found much more expensive QALYs -- on the order of $150,000 per patient -- which would make CT lung cancer screening unreasonably expensive. As a result, Black and colleagues plan to study McMahon's group's lung cancer policy model carefully to evaluate its cost data.

"We will have to see what assumptions are being made and why we have different estimates," he said. "Obviously we're making some different assumptions and the final answer will be in the NLST data. The good news is that everybody is very interested in the results ... and I'll be very happy when I'm done."