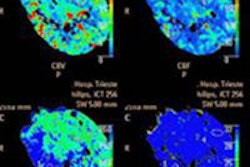

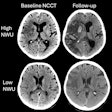

CT perfusion (CTP) imaging of the brain brings multiple diagnostic benefits for ischemic stroke patients, but it's not needed when deciding whether to revascularize, according to neuroradiologist Dr. Michael Lev from Massachusetts General Hospital. CT angiography (CTA) can also be used as a surrogate for diffusion-weighted MRI to determine infarct size.

In the setting of a blood clot in the middle cerebral artery and acute stroke symptoms, it's the measurement of cerebral blood flow from CTA -- not CTP, not noncontrast CT, not cerebral blood volume, and apparently not CTA source images -- that makes a good MR surrogate for determining the benefit of revascularization with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), if you know what to look for, Lev said.

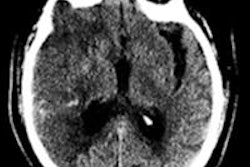

Thanks to solid data from the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) trial from the 1990s, tPA has long been considered safe within three hours of stroke onset so long as there's no hemorrhage, and given those factors the treatment decision depends largely on how much of the brain is already dead. Diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI-MRI) is also unnecessary for determining infarct size -- good news considering that available MRI scanners can be scarce in the emergency setting, said Lev, who is director of emergency neuroradiology and the radiology neurovascular lab at Massachusetts General Hospital.

"If there's no hemorrhage and the [infarct] core is small, you're probably going to want to bring that patient to treatment," Lev said in a June presentation at the International Society for Computed Tomography (ISCT) annual meeting. The reasons driving this conclusion need a little explanation but are becoming increasingly solid with emerging data, he said.

"We have to understand the role of imaging in making treatment decisions now because all imaging is driven by the clinical application, and because there is good level 1 prospective evidence from a randomized trial [NINDS trial, NEJM, December 14, 1995, Vol. 333, pp. 1581-1588] that tPA within three hours is safe and effective ... as long as there's no hemorrhage, and there really isn't a role for advanced imaging," Lev said. "On the other hand, early ischemic signs in more than one-third of [middle cerebral artery (MCA)] territory are generally considered exclusionary criteria for tPA and IV-tPA as well."

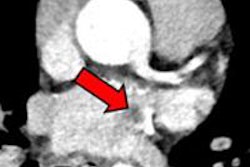

CTA finds the problem

Endovascular treatment does require a therapeutic target, and CTA is the best modality -- better than MR angiography and ultrasound -- to visualize stenoses and occlusions that can be treated, he said. But the clinician also needs to know how much of the brain is already dead because this variable affects the safety of revascularization with tPA and even IV-tPA.

If more than a third of the middle cerebral artery territory is already dead, the risk of hemorrhage rises, Lev said. Large DWI-based lesion volumes at admission are associated with poor outcomes, making revascularization a poor choice in these cases, he said.

"So the real question becomes how we estimate how much of the brain is dead," he said. "Measure it in volume and it turns out 70 to 100 mL is the magic number -- that's about one-third of the MCA territory."

This is a kind of dividing line between safe and risky revascularization therapy. But if the clinician doesn't have diffusion-weighted MRI available, then the extent of brain tissue death becomes an open question that requires an answer.

Will CTA do the job? It can when the extent of collateral vessels CTA visualizes is taken into account. When present in sufficient volume, collateral vessels can feed the brain tissues surrounding an infarcted vessel, limiting the damage from ischemic stroke. Lev's group recently showed that the collateral score derived from these vessel volumes correlates with DWI volumes (American Journal of Neuroradiology, August 2012, Vol. 33:7, pp. 1331-1336).

Understanding the patient

But the treatment decision also requires an understanding of the patient and the setting, he said.

"Are we trying to treat patients using conventional therapies and conventional time windows where we have high levels of evidence, and it's only a question of ruling out the ones most likely to bleed?" Lev asked. In this case, imaging becomes a rule-out process of safety-related exclusion criteria, and CTA doesn't inform the treatment decision.

"Or are we talking about novel therapies, or wake-up strokes, or strokes of unknown onset time?" Lev said. "That's when we not only have to rule out risk, we have to rule in benefit. We have to show a target for therapy, and that's when [CT] perfusion may come in because we don't have a high level of evidence to treat all comers, and so the population needs to be individualized."

Not all M1 occlusions are the same, though they all share a mismatch between mean time to peak and mean transit time, he said. The differences include wide variability in the extent of dead brain at admission, and the extent of infarct growth.

1 | Next page