Noninvasive imaging techniques have long proved valuable for digging up the stories of fossils without damaging them. In a new study published online in Radiology, German researchers have gone a step further, making a carbon copy of a dinosaur vertebra using CT data and 3D printing.

The researchers were able to classify the fossil as belonging to the genus Plateosaurus, as well as obtain new information about its condition. However, the main goal was to test the group's method for creating a 3D model of an unprepared fossil (i.e., still encased in sediment), using a CT dataset to separate the fossilized bone from the surrounding materials, according to the authors. The 3D copy of the vertebra was accurate, they concluded, providing a nondestructive option for future research.

With such methods, a "digital dataset and, ultimately, reproductions of the 3D print may easily be shared, and other research facilities could thus gain valuable informational access to rare fossils, which otherwise would have been restricted," said senior author Dr. Ahi Sema Issever, from Charité Campus Mitte, in a release from RSNA.

The research was conducted jointly by the Museum für Naturkunde, the 3D Laboratory of Technische Universität, and the department of radiology at the Charité Campus Mitte, all of which are located in Berlin (Radiology, November 20, 2013).

Keeping the jacket on

The fossil examined by the group was surrounded by sediment as well as a "jacket" made of plaster and burlap, initially applied to protect the bone. Traditionally, preparing such a fossil for examination involves removing the jacket and sediment, which is time-consuming and can also damage the item, according to lead author Dr. René Schilling and colleagues.

While CT and 3D printing have been used for fossils before, the copies "were limited to fossilized objects already separated from their surrounding sediment matrix," the authors wrote. Their hope was to successfully create a 3D model of an unprepared fossil, using CT data from the entire combined structure -- sediment, plaster, and all.

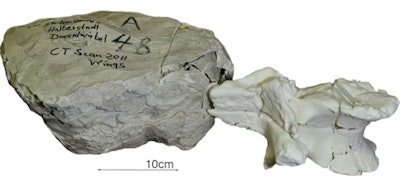

The original incorrectly labeled plaster jacket and the researchers' 3D print of the vertebra. All images courtesy of RSNA.

The original incorrectly labeled plaster jacket and the researchers' 3D print of the vertebra. All images courtesy of RSNA.To test the feasibility of their technique, Schilling and colleagues applied it to an unidentified fossil from the Museum für Naturkunde. The fossil was part of a group collected in the early 1900s from two excavation sites, one in modern-day Tanzania and the other in Germany, and stored in the museum. During World War II, the museum was struck in the bombing of Berlin, which destroyed some fossils and buried others in rubble, the authors wrote.

The excavation projects used different or somewhat overlapping labeling systems, which added to the confusion in trying to re-sort the fossils after the bombing. As a result, some of them remained unclassified.

The researchers began by scanning the unprepared fossil with a 320-slice MDCT system (Aquilion One, Toshiba Medical Systems). They used a helical scan mode with a 1-sec rotation time, along with tube voltage of 135 kVp and tube current of 450 mA. Axial images were acquired with 500-µm section thickness, while subsequent multiplanar reconstructions (axial, coronal, and sagittal) were calculated with a section thickness of 3 mm.

Schilling and colleagues used a "marching cubes" computer graphics algorithm to create a representation of the object's surface from their voxel CT dataset. They also applied a postprocessing step to further clarify the shape of the fossilized vertebra within the sediment before 3D printing.

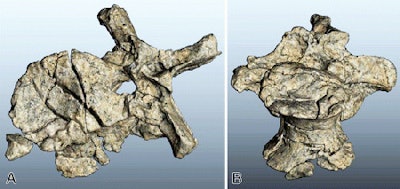

Virtual 3D reconstructions of the vertebra obtained after the surrounding sediment matrix and plaster were digitally removed through segmentation of the CT dataset.

Virtual 3D reconstructions of the vertebra obtained after the surrounding sediment matrix and plaster were digitally removed through segmentation of the CT dataset.Once the vertebra geometry was finalized, a 3D print was created using a selective laser sintering (SLS) machine (Formiga P 100, EOS). With SLS, a laser is used to heat and fuse powder in whatever shape is specified by the data, and a new object is subsequently formed layer by layer.

History revealed

Visually identifying the fossilized bone within the wrapped object at CT was relatively easy due to the different attenuation values of the materials, according to the authors. Attenuation was approximately 2,362 HU for the bone, compared with 556 HU for the plaster layer and 1,896 HU for the sediment.

Based on the scans, Schilling and colleagues concluded that the fossil was a Plateosaurus dorsal vertebra, and with the help of old excavation drawings and lists, they were also able to identify its origin within the excavation site in Germany, near Halberstadt.

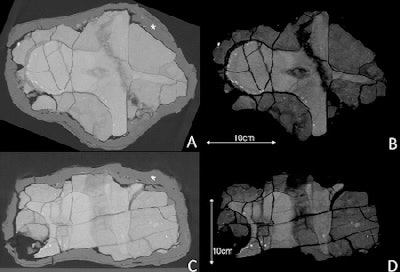

Coronal (A, B) and sagittal (C, D) reconstructions of the fossil using different window levels and widths. Numerous fracture lines are visible.

Coronal (A, B) and sagittal (C, D) reconstructions of the fossil using different window levels and widths. Numerous fracture lines are visible.CT also revealed multiple fracture lines in the fossil, along with a major fracture zone that divided the vertebra into ventral and dorsal halves. In the anterior part of the object, the images showed a space between the plaster layer and the remaining fossil. The space contained small bone fragments, suggesting that damage occurred after the fossil was wrapped, they wrote.

Upon examination of the fracture lines and other characteristics, the 3D print of the vertebra appeared to be an accurate copy of the virtual 3D reconstruction, according to the authors.

"Therefore, our approach may be a novel alternative to conventional methods that allows preservation of these rare objects of old excavations," they wrote.

In addition, as 3D printing becomes increasingly popular, preservation will continue to be an important feature of the technology. It enables limitless copies of rare items to be circulated among researchers, advancing scientific knowledge without risking damage to the object.

"Just like Gutenberg's printing press opened the world of books to the public, digital datasets and 3D prints of fossils may now be distributed more broadly, while protecting the original intact fossil," Issever said.