CT scans of coronary artery calcium in modern Egyptians revealed that they had patterns of atherosclerosis nearly identical to those of ancient Egyptian mummies -- right down to the affected anatomy, according to a new study in Global Heart.

The international group of researchers scanned modern Egyptians and compared the exams to CT scans previously performed on mummies. They found that the development of atherosclerosis followed the same patterns in both cohorts.

The discovery isn't just of interest to archaeologists -- it yields important lessons that could inform screening for coronary disease today, wrote lead investigator Dr. Adel Allam from Al-Azhar University; Dr. Jagat Narula, PhD, editor in chief of Global Heart and associate dean for global health at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; and their colleagues from the Horus project, a group using CT to scan mummies (Global Heart, July 31, 2014).

The correlation between ancient and modern Egyptians in the number of vascular beds involved with atherosclerosis was "striking," the study authors wrote. The disease tended to begin in the aortoiliac beds almost a decade earlier than in the coronary and carotid beds.

"Our major conclusion was that age is the most consistent factor related to the development and severity of atherosclerosis in ancient and modern Egyptians," Allam wrote in an email to AuntMinnie.com. "The second important conclusion was that when age range was matched between the two groups, both incidence and severity of atherosclerotic disease were not significantly different between ancient and modern Egyptians."

Striking correlations

Atherosclerotic vascular disease is a major global health problem that continues to cause significant morbidity and mortality. While it's often thought of as a modern disease arising from today's lifestyles and poor diets, it does not really differ from what is found in the blood vessels of humans who lived 4,000 years ago, according to the authors.

In an April 2011 study in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, Allam et al sought to detect vascular calcifications in ancient Egyptians living as long as 3,500 years ago, but similarity to the development of disease today has been an open question, the authors wrote. Given the differences in lifestyle and mean age at death between the cohorts, the researchers wondered about any similarities in vascular disease.

"Accordingly, we thought to compare patterns and demographic characteristics of vascular calcifications between modern and ancient Egyptians to better understand the determinants of atherosclerosis," Allam and colleagues wrote.

The study team scanned 178 consecutive modern Egyptian patients, all of whom had been referred by their primary physicians for cancer staging with PET at the Alfa Scan Outpatient Radiology center in Cairo. All patients were scanned on a Gemini TF PET/CT scanner (Philips Healthcare) in a single session from the base of the skull to the knee. Images were acquired using 1-mm slices and an average time interval of 0.8 msec. Interpretation consisted of searching for vascular calcifications in different vascular beds.

These results were compared with whole-body CT scans of 76 Egyptian mummies (3100 B.C.E. to 364 C.E.) scanned for the 2011 publication on a six-detector-row Emotion 6 scanner (Siemens Healthcare). Five experienced cardiovascular imaging physicians among the Horus investigators (who also performed the living human study) looked for cardiac and vascular calcifications in the carotid, coronary, aortic, iliofemoral, and peripheral vascular beds. Mummy selection was based on the specimens being in a good state of preservation rather than on random selection, the study team noted.

Based on the number of vascular beds affected with atherosclerosis, the group ranked the extent of disease from 0 to 5 (0 beds affected = no disease, 1 or 2 beds = mild disease, 3 or more beds = severe disease).

Similar results despite cohort differences

Age was the biggest difference between the ancient and modern subjects, Allam and colleagues noted. The mean age of the modern Egyptians was 52.3 ± 15 years (range, 14 to 84), whereas the estimated age at death of the mummies was 36.5 ± 13 years (range, 4 to 60 years, p < 0.0001).

Correspondingly, vessel calcification was found in 108 (60.7%) of the 178 modern patients, compared with 26 (38.2%) of the 76 ancient Egyptian mummies (p < 0.001). The incidence of vascular calcification was strongly related to age irrespective of sex differences, and the extent of disease was also related to age, the authors wrote.

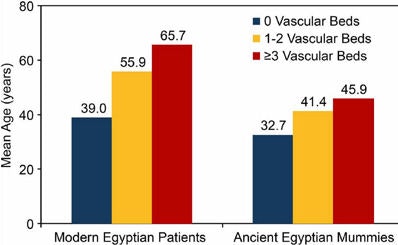

Vascular calcification severity in relation to mean age in modern and ancient Egyptian groups. Images republished with permission of the World Heart Federation and Allam et al (Global Heart, July 31, 2014).

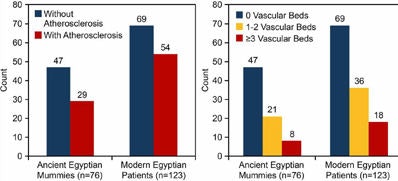

Vascular calcification severity in relation to mean age in modern and ancient Egyptian groups. Images republished with permission of the World Heart Federation and Allam et al (Global Heart, July 31, 2014). Incidence of vascular calcification present or absent and extent of vascular disease among ancient and modern Egyptians after excluding modern patients > 60 years of age.

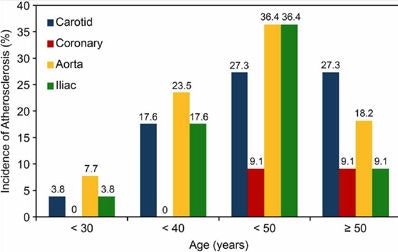

Incidence of vascular calcification present or absent and extent of vascular disease among ancient and modern Egyptians after excluding modern patients > 60 years of age. Vascular bed distribution of calcification in the ancient Egyptian group.

Vascular bed distribution of calcification in the ancient Egyptian group.The mean age of modern patients who had vascular calcification was 61 ± 10.5 years, compared with 39 ± 10.1 years for those with no evidence of calcification (p < 0.0001). The mean age of the modern Egyptians with mild disease was 56 ± 9.5 years; for those with severe disease, mean age was 65.7 ± 9.2 years (p < 0.0001).

The findings were similar among the Egyptian mummies, with a mean age at death of 42.7 ± 10.2 years for those with any evidence of atherosclerosis, compared with 32.7 ± 12.4 years for those without evidence of vascular calcification (p < 0.0001). For mummies with evidence of mild disease, the mean age at death was 41.4 ± 10.9 years, and for those with severe disease, the mean age was 45.9 ± 7.9 years.

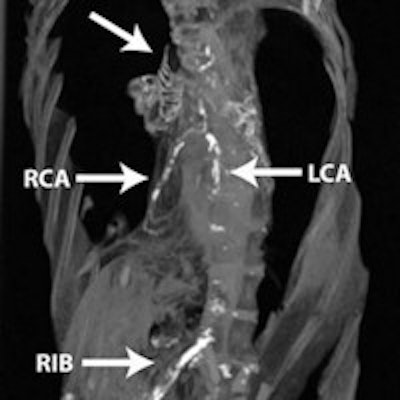

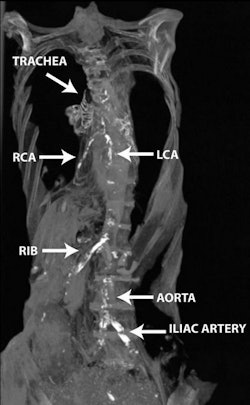

CT image of the mummy of a princess who lived during the Second Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt shows calcifications in the coronary and iliac arteries. She had diffuse atherosclerosis. (This image only is from JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, April 2011, Vol. 4:4, pp. 315-327.)

CT image of the mummy of a princess who lived during the Second Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt shows calcifications in the coronary and iliac arteries. She had diffuse atherosclerosis. (This image only is from JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging, April 2011, Vol. 4:4, pp. 315-327.)No ancient Egyptian mummy died at an age older than 60 years, which led the investigators to limit the living cohort to age 60 as well. When a subgroup analysis was performed, "it was quite striking to note that the pattern of progression of vascular atherosclerosis was the same among modern and ancient Egyptians," Allam and colleagues wrote. Additionally, the disease pattern was the same across different age groups.

In both ancient and modern populations, "vascular calcification starts at the peripheral vascular bed (iliofemoral then aortic beds), then spreads to the target vessels (coronary and carotid beds) around a decade later than the onset of aortoiliac calcification," the authors wrote. There was also a trend toward higher incidence of vascular calcification among female mummies, but not modern Egyptians. Allam and colleagues hypothesized that the women may have been exposed to household smoke.

"The fact that atherosclerosis, as evidenced by vascular calcification, was seen on whole-body CT examination of ancient Egyptian mummies has changed our belief that vascular atherosclerosis is a disease related to a modern lifestyle and has demonstrated that our understanding of the causative risk factors of this disease are less than perfect," they wrote. "This has deepened our interest to better study demographics and patterns of this disease in both ancient and modern Egyptians."

Could it be that the mummy specimens were atypical of the ancient population as a whole because they were among the elites of ancient Egyptian society and thus were more likely to be carefully preserved at death? And might these elites have had a less healthy lifestyle than the commoners of the time?

"We should be surprised to see much disease among ancient Egyptians and we may start to question if this was perhaps caused by them having more access to fatty foods and other causative risk factors, as they were royalties or elites in their communities," Allam told AuntMinnie.com. "But we have previously reported similar results in other cultures, Native North Americans and ancient Peruvians as well as Aleutian Island hunter-gatherers -- all with different diets and also different lifestyle patterns and geographical regions. Hence, other factors may be responsible, such as chronic infection and genetic predisposition."

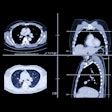

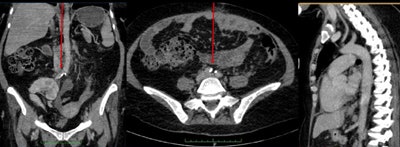

Coronal, axial, and sagittal CT multiplanar reformatted images from a 47-year-old modern Egyptian woman with hypertension but no other risk factors for atherosclerosis. There is mild aortoiliac disease but no coronary or carotid calcium.

Coronal, axial, and sagittal CT multiplanar reformatted images from a 47-year-old modern Egyptian woman with hypertension but no other risk factors for atherosclerosis. There is mild aortoiliac disease but no coronary or carotid calcium.In a previous analysis of large numbers of modern patients (the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, or MESA), abdominal aortic calcification was shown to be strongly associated with subclinical cardiovascular disease in other vascular beds, including the coronary, carotid, and leg arteries, the authors noted. This led investigators to conclude that the high prevalence of abdominal aortic calcification, even when coronary or carotid disease was not present, might suggest that atherosclerosis began earlier in the abdominal aorta compared to event-related vascular beds such as the coronary arteries.

And if disease begins in the abdomen before it reaches the coronaries, maybe that's where screening should start, according to Allam. "Occurrence of aortoiliac calcification a few years earlier than the coronary arteries could be used as an important screening tool for effective preventive cardiology strategies," he wrote in his email.

"Our knowledge on risk factor patterns among ancient Egyptians, including associated conditions such as diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and hypertension, is incomplete," the authors concluded. "Further studies comparing varying environmental and genetic predispositions to the development of atherosclerosis between ancient and modern Egyptians are warranted."