A patient presenting with a foreign body -- an object that has been swallowed, breathed in, or inserted -- is a common scene in the emergency room (ER). And radiologists are just the experts to coach ER doctors on how to diagnose these patients, according to a review published in the Annals of Emergency Medicine.

Foreign bodies can include everything from coins, buttons, batteries, and magnets to knives, nails, and packets of drugs, and ER physicians tend to be the first point of contact for these patients. But they aren't always aware of foreign bodies' particular imaging qualities -- or the most appropriate imaging modality or technique for diagnosis and follow-up, wrote researchers from Emory University. To help ER physicians, Dr. Hsiang-Jer Tseng and colleagues authored an overview article that outlines these qualities and techniques.

"Radiologists can be much more helpful to ER physicians besides just telling them whether there is a foreign body or not," Tseng told AuntMinnie.com via email. "There are many important imaging features that can dramatically change the clinical management of foreign-body-related accidents. That's the main motivation behind this article -- to equip ER physicians with this knowledge so they can better utilize radiology exams to guide their clinical decision-making."

A patient with history of traumatic brain injury presented with abdominal pain and vomiting; was found to have small bowel obstruction on radiograph and incidentally also had multiple round, opaque foreign bodies. A retained bullet from a prior gunshot was also noted. All images courtesy of Dr. Hsiang-Jer Tseng.

A patient with history of traumatic brain injury presented with abdominal pain and vomiting; was found to have small bowel obstruction on radiograph and incidentally also had multiple round, opaque foreign bodies. A retained bullet from a prior gunshot was also noted. All images courtesy of Dr. Hsiang-Jer Tseng.Coins, batteries, and knives

X-ray is the go-to modality for diagnosis and follow-up of patients presenting with foreign objects. Clinicians need to know that these items have varying radiopacity and radiographic visibility, depending on their type. For example, plastic toys are visible on x-ray when placed in a basin without water, but they gradually become less visible as water is added. The key concept is that an object's visibility can depend not only on its size and radiopacity, but also on its anatomic location, the patient's body size, and the surrounding anatomic structures, according to the researchers (Ann Emerg Med, August 27, 2015).

"A foreign body that is radiographically visible in the airway may not be visible when it is embedded in soft tissue; a foreign body that is radiographically visible in the foot may not be visible when it is embedded in the abdomen where soft-tissue thickness is greater," they wrote.

A patient who swallowed two AAA batteries. Images above and below show batteries progressing through the colon.

A patient who swallowed two AAA batteries. Images above and below show batteries progressing through the colon.Foreign objects in the esophagus account for about 1,500 deaths per year in the U.S., and although most pass through without incident, about 10% to 20% require intervention. Children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years make up the majority of foreign body ingestion cases. Intentional ingestion of foreign bodies is more common in adults and tends to be associated with psychiatric illness, intellectual disability, substance abuse, incarceration, or drug smuggling ("body packing," or swallowing drug-filled packets), the researchers wrote.

"Deliberate efforts are required to ingest long foreign bodies, such as toothbrushes, pencils, and utensils," they wrote. "Such incidents are often intentional and occur more frequently in patients with psychiatric illness."

| Imaging characteristics of common foreign body materials | |||||

| Material | X-ray | Ultrasound | CT* | ||

| Wood | Radiolucent (appears dark) | Hyperechoic structure with posterior shadowing; dirty shadowing if significant air content | HU can be negative due to air, but can increase as wood absorbs more water | ||

| Plastic | Radiolucent | Hyperechoic structure with posterior shadowing | HU between 100 and 500, depending on composition and density | ||

| Stone | Radiopaque (appears light) | Hyperechoic structure with posterior shadowing | High HU, usually more than 1,000 | ||

| Glass | Radiopaque | Hyperechoic structure with "ring down" artifact | HU varies depending on density, from 500 to 2,700 | ||

| Metal | Radiopaque, except for thin aluminum | Hyperechoic structure with "ring down" artifact | HU of more than 3,000, except for aluminum, which has HU of 700 to 800 | ||

Many frequently swallowed objects, such as fish or chicken bones, plastic, wood, or carbonated soft-drink tabs, may not show up on x-ray, the authors wrote. So if a clinician has a high suspicion due to the patient's symptoms that there is a foreign body, it's wise to evaluate the patient further with CT or endoscopy.

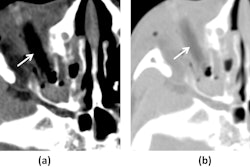

Coins are the most commonly ingested type of foreign body and account for up to 70% of the cases in children, they wrote. But make sure it's a coin and not a button battery, Tseng told AuntMinnie.com. The battery will have a "halo" sign at high magnification on x-ray.

Dr. Hsiang-Jer Tseng from Emory University.

Dr. Hsiang-Jer Tseng from Emory University."If there's a coin-like metallic foreign body in the esophagus on chest x-ray, it's very important to determine whether it's actually a button battery," he said. "Children may not be able to tell you exactly what they swallowed, and if a button battery gets stuck in the esophagus, it can leak caustic material, which could lead to esophageal perforation, hemorrhage, and even death."

In situations where a patient has aspirated a life-threatening object, bronchoscopy and laryngoscopy are standard diagnosis methods. But for nonlife-threatening items, two-view chest and neck x-rays can be used for the initial evaluation, the authors wrote. When it comes to detecting illegal drugs ingested by condom, balloon, or plastic, x-ray's performance can be variable, with false-negative rates as high as 23%; CT with intravenous contrast works better, according to Tseng and colleagues.

In any case, recognizing the clinical presentation, imaging management, and imaging characteristics of various foreign objects is crucial to accurate diagnosis and treatment, Tseng said.

"With a better understanding of these important imaging features and recommendations, ER clinicians can prevent misdiagnosis of life-threatening foreign-body-related complications and avoid ordering the wrong imaging modality that may give subpar results or delay diagnosis," he said.