CHICAGO - In an amazing 26-hour operation, a multidisciplinary team used CT scans and a 3D-printed model of the organs of conjoined twins to help perform a successful separation. Details of the effort were presented at this week's RSNA conference.

"This case was unique in the extent of fusion," said Dr. Rajesh Krishnamurthy, chief of radiology research and cardiac imaging at Texas Children's Hospital. "It was one of the most complex separations ever for conjoined twins."

The children had separate hearts, although both hearts were in the same chest cavity. Their livers were fused, but the scans and 3D printing revealed a line of demarcation that had few blood vessels and would allow surgeons to separate the liver. The girls also shared the chest wall, pericardium, diaphragm, liver, intestines, urinary tract, gynecologic tract, and pelvis.

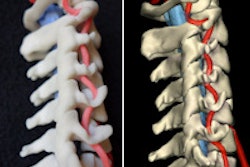

3D-printed model of the twins' conjoined anatomy.

3D-printed model of the twins' conjoined anatomy.The children, Knatalye and Adeline Mata of Lubbock, TX, were born on April 11, 2014. The surgery was attempted 10 months later. To prepare for the separation surgery, Krishnamurthy and colleagues performed volumetric CT imaging with a 320-detector-row scanner, administering intravenous contrast separately to each twin to enhance views of vital structures and plan how to separate the girls.

The team translated the CT imaging results into a color-coded physical 3D model, with skeletal structures and supports made of hard plastic resin and organs built from a rubber-like material. The livers were printed as separate pieces of the transparent resin, with major blood vessels depicted in white for better visibility. The models were designed so that they could be assembled together or separated during the surgical planning process. The surgical team used the models during the exhaustive preparation process leading up to the surgery.

The specialist team included 12 surgeons, six anesthesiologists, and eight surgical nurses. At a press conference, Krishnamurthy said that creating the 3D printed model -- which took about a week -- was followed by several weeks in which the team discussed how the procedure would work. Finally, the girls were taken into the operating room.

The model was almost perfectly accurate, allowing the surgical team to proceed as they had planned in their simulations, he said.

Press conference moderator Dr. Dorothy Bulas, a professor of pediatrics and radiology at the Children's National Health System in Washington, DC, said, "This procedure took 26 hours, but without the 3D printed model it easily could have take two to three days. I think that 3D printing is a wonderful tool that will help put radiologists back in the picture -- it's exciting."

Conjoined twins, or twins whose bodies are connected, account for approximately one of every 200,000 live births. Survival rates are low, and separating them through surgery is extremely difficult because they often share organs and blood vessels, Krishnamurthy noted.

Knatalye returned home in May of this year and her sister Adeline came home a month later. Krishnamurthy said the girls are basically normal. They have knee weakness that will need to be addressed further to allow them to walk. They also have thin chest walls due to the loss of rib material where they were joined.

Although sorting out which twin received which reproductive organs was problematic, Krishnamurthy said the surgical team was able to follow the blood vessel linkages, and it will be possible for the twins to have their own babies, he said.

He expects the combination of volumetric CT, 3D modeling, and 3D printing to become a standard part of preparation for the surgical separation of conjoined twins, although barriers remain to its adoption.

"The 3D printing technology has advanced quite a bit, and the costs are declining. What's limiting it is a lack of reimbursement for these services," he said. "The procedure is not currently recognized by insurance companies, so right now hospitals are supporting the costs."

The hospital and the surgical team donated their services in the landmark surgery, Krishnamurthy said.