With the aid of CT, computer-aided design (CAD), and 3D printing, researchers at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center are bringing new functionality, new freedom, and a sense of normalcy to the lives of military personnel who have been gravely wounded in battle.

All told, researchers at the hospital's 3D Medical Applications Center in Bethesda, MD, have built more than 20 sophisticated custom prostheses and attachments that have allowed patients with missing limbs to return to sports and activities they used to love. A presentation at the RSNA 2015 meeting in Chicago described three projects that combined specialty hardware with extremity prostheses using CT and computer-aided design software.

"Rock climbing, swimming, ice skating" -- there is much that standard prosthetics materials and manufacturing can do to restore mobility in patients who have lost limbs, "but there are some needs for specialty devices that additive manufacturing [3D printing] can provide," said Peter Liacouras, PhD. His presentation focused on three customized applications: a wineglass holder, hockey skate adapters, and a weightlifting adapter.

Patients coming out of rehabilitation after losing limbs -- improvised explosive devices (IEDs) encountered in Iraq were a persistent cause -- tend to be young and accustomed to being very active. They are motivated to return to complex activities such as kayaking, skiing, and scuba diving that used to occupy their free time, Liacouras said.

Custom prostheses can facilitate such specialized activities, and they can often be engineered relatively easily, he said.

Liacouras and colleagues Gerald Grant, DMD; Dr. John Lichtenberger III; and Dr. Vincent Ho work closely with the prosthetics department to design and create the custom prostheses, each designed to fit a particular prosthetic socket or terminal device. To accomplish this, various impressions, thermoplastic molds, and specialty items are typically scanned using CT and then digitally reconstructed to produce a virtual 3D model. The engineer then uses the model to design the complementary part that attaches to the wearer's body.

"CT is a valuable resource to us because some of these specialty devices have organic shapes and undercuts that might be difficult to [reproduce without] a CT scanner, especially if you have to articulate one surface to another," Liacouras said.

In vino veritas

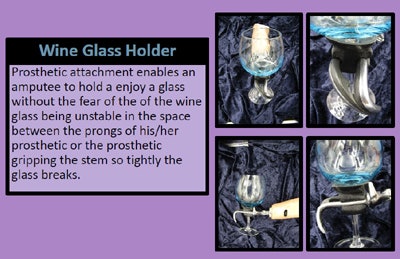

The first product was designed for a bilateral amputee who had lost his hands, but not the desire to toast special occasions with his spouse.

"The prosthetic hook has a very strong grip strength, so if they were just to grab the stem of the wineglass it would probably break or be unstable," Liacouras said.

Pondering the problem and staring at the hook for a while led Liacouras to an idea: Use CT to reconstruct an impression of the empty space on each side of the stem, between the prongs of the prosthetic hook, to wrap around the wineglass and hold the glass without breaking it.

"This was done in 5-mm slices -- not totally ideal, but it provided the general contours," he said. "There are 3D surface scanners available, but the metal is very hard to scan and the undercuts would be extremely difficult to obtain."

The wineglass holder was printed using a flexible material on an Objet500 Connex2 3D printer (Stratasys). It attaches to the hook prosthesis and includes a slot to hold the stem of the glass, he said.

All images courtesy of Peter Liacouras, PhD, at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

All images courtesy of Peter Liacouras, PhD, at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.Back on the ice

Another project involved a bilateral amputee who wanted to start ice skating again.

"This patient didn't just want to strap on the skates to his prosthetic feet because they're made of foam and he never thought they'd be tight enough," Liacouras said.

The group acquired a CT scan of the blade holder and reconstructed the prosthetic piece using a 3D program for reconstructing anatomic features. The skates and the socket piece for the prosthesis were then merged using a series of posts. The team paid special attention to the adjustability of the ankle joint and the center of gravity.

"We didn't know how the patient would be because he didn't have active ankle joints and those are very important when you're ice skating," Liacouras said.

3D printing was performed using a titanium alloy on an electron-beam melting machine (Arcam), and the finished product included a tool to tighten the bolts on the adjustable components.

"This is him in action -- this patient was absolutely amazing," Liacouras said of a video clip of the patient skating.

Pumping iron

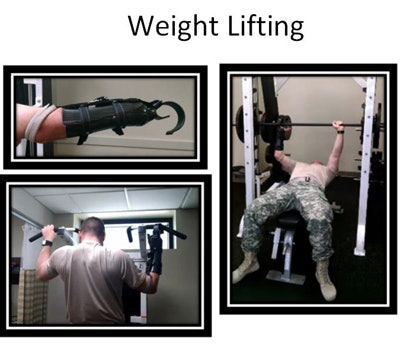

The third case was a special socket designed for a partial hand amputee "who thought he'd never be able to lift weights again," Liacouras said.

"This specialty socket had to fit a very unique shape, so we actually took the socket to the CT scanner, scanned it and reconstructed it, and created our CAD file, keeping the anatomy of the hand in mind not to produce too much of a difference in biomechanics for pushing and pulling exercises such as bench presses and pullups," he said.

To handle both tasks, the titanium adapter had to be laminated into the carbon fiber socket of the prosthesis. The device allows the patient to lift with one arm at a time or with both simultaneously. The biomechanics are close but not perfect, so the team is currently working on a new design, Liacouras added.

"CT scans can be used not just for anatomic data, but to produce many other things," including prosthetic attachments, he said.

Note: AuntMinnie.com provided equipment names for informational purposes; the investigators do not endorse the use of any specific commercial product.