The return of black lung disease in coal workers isn't just limited to the U.S. In a new study, Australian researchers used x-ray and CT to document the presentation of lung diseases in coal miners -- cases that could have been detected earlier if better screening programs were in place.

Researchers found that diseases related to coal dust exposure such as coal workers' pneumoconiosis (also known as black lung disease) have a specific presentation on x-ray and CT exams that make them readily apparent to trained readers like radiologists. But many of the subjects in their study presented with disease that was probably more advanced than necessary, according to the study, published February 11 in the Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Oncology.

"Overall, approximately one-third of the study subjects with pneumoconiosis were diagnosed at a time when their radiological presentation would be considered severe disease," wrote a team led by Rhiannon McBean, PhD, of Wesley Hospital in Brisbane. "Delayed medical diagnosis is a likely cause of this high rate of advanced disease."

The black scourge

Workers who spend years in coal mines face a variety of occupational diseases, from coal workers' pneumoconiosis to chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and dust-related diffuse fibrosis. Government programs set up to screen miners were effective in reducing the incidence of these diseases but were perhaps victims of their own success: Emphasis on screening declined as the incidence of occupational lung disease dropped.

At the same time, the nature of coal mining has changed in ways that make it more hazardous than ever to miners. As easy-to-reach coal seams play out, miners have begun digging deeper into rock like sandstone, a process that releases fine particles of silica into the air. When inhaled into the lungs, these particles are perhaps even more dangerous than coal dust.

In the U.S., the federal government has operated a program since 1969 in which miners are screened, with the images interpreted by registered clinicians (B readers). Australia had a similar program from 1984 to 2016, according to McBean. But participation in the program was only mandatory for miners in "high dust roles," a classification that was unclear as there were no guidelines that established what a high dust role was. What's more, unlike the U.S. program, Australia's program didn't require radiologists to be trained in occupational reading.

In 2015, the first case of coal workers' pneumoconiosis in 30 years was reported to the government of Queensland. This resulted in an "overhaul" of the coal miner screening program, which subsequently led to the diagnosis of the largest number of lung disease cases related to coal mine dust in the state's history, according to the authors.

In the current study, McBean and colleagues decided to examine the cases that had been reported to learn more about the radiological presentation of occupational black lung disease, in particular as it presents on x-ray and CT exams.

The researchers investigated a series of 79 individuals who had received a diagnosis of coal mine dust lung disease since 2015. Radiological findings were characterized using the International Labour Office (ILO) classification system and the International Classification of HRCT for Occupational and Environmental Respiratory Diseases (ICOERD).

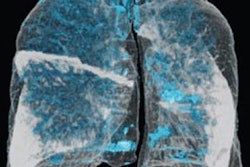

Among the 79 men, there were 56 cases of pneumoconiosis, which demonstrated as widespread opacities with bilateral upper zone predominance, according to the authors. In these cases, most of the lung was affected, with 72% of lung zones showing opacities on x-ray and 79% on high-resolution CT.

Some 71% of the miners with pneumoconiosis had ILO category 1 disease, while 21% had advanced disease. What's more, 81% of the those with pneumoconiosis had at least one feature on images that indicated exposure to respirable crystalline silica.

Image of a miner with coal workers' pneumoconiosis, classified as ILO 2/1. Image courtesy of Rhiannon McBean, PhD.

Image of a miner with coal workers' pneumoconiosis, classified as ILO 2/1. Image courtesy of Rhiannon McBean, PhD.For other lung diseases, 18 individuals had chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD), characterized by widespread emphysema that was not dominant in any one lung zone. Five individuals had dust-related diffuse fibrosis, which presented as radiologically severe disease with irregular opacities that were dominant in lower lung zones.

High presence of silica exposure

The radiological findings that were of particular interest in the study were the high burden of opacities found on x-ray and CT images, as well as the presence of features associated with silica exposure in most of the individuals, according to McBean and colleagues.

The researchers closed by noting that their case series illustrated the "broad spectrum of occupational lung diseases that occur in coal industry workers." Pneumoconiosis was the most common lung condition, and one-third of the cases were diagnosed with what would be considered severe disease based on imaging findings.

What caused the high incidence of advanced disease? The authors postulated this was due to the lack of an aggressive screening program, manifested by "poor-quality chest radiographs" and a lack of image review by specialist chest radiologists who had experience with occupational lung disease. Indeed, they expressed surprise that the cases in their study were not detected earlier, given the high burden of opacities on images.

McBean and colleagues concluded that miner exposure to silica was most likely the reason for the prevalence of advanced disease in their study, and they recommended that more studies be conducted to document the prevalence of lung disease related to coal dust exposure in Australia, as well as the prevalence of advanced pneumoconiosis.

"Chronic exposure to [respirable crystalline silica] is recognized as more hazardous than coal dust alone and has been associated with higher grades of disease, faster disease progression, and a greater risk of development of [progressive massive fibrosis] and lung cancer," they wrote.