Nearly every day, it seems, the media and medical experts find a way to remind us that heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S. Given the general population's propensity for unhealthy lifestyles and unwise dietary choices, this news is not a huge surprise. But cardiac arrest is the leading cause of death in athletes, a segment of the U.S. population that, with their peak conditioning and youthfulness, should be immune to average Joe ailments.

In May 2005, 14-year-old Michael Monteleone, a high school baseball player from Lincoln, RI, died during a game from an irregular heartbeat. Another 14-year-old, Matthew Thomas of Victoria, TX, died in 2003 during football practice, also from cardiac arrhythmia. Had they undergone preparticipation screening with echocardiography and MRI, you wouldn't be reading about their deaths now.

In the U.S., however, such screening is rarely done. Statistically, sudden death of athletes from cardiovascular disease is rare. The National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reports there were 211 heart-related deaths in U.S. high school and college football players from 1931-2004. In all other sports, there were 226 heart-related deaths from 1982-2004.

According to a recent review article, heart-related death occurs in "one in 200,000 high school athletes per year. The most common causes ... are hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [HCM] (36%), coronary artery anomalies (19%), and increased cardiac mass not diagnostic of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (10%). The remaining causes include ruptured aorta, aortic stenosis, myocarditis, coronary artery disease, and mitral valve prolapse" (Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, April 2005, Vol. 433, pp. 38-49).

|

| In May 2005, Brendon Wen, age 35, passed away suddenly after finishing his last event at the Pacific Masters Championship swim meet in Pleasanton, CA. Wen, a San Francisco-based criminal defense attorney, had just finished the 200-yard butterfly. He had been swimming since age 9, and had played competitive water polo while attending the University of California, Davis. The official cause of death was cardiorespiratory failure due to hypotrophic and arteriosclerotic cardiovascular disease (San Francisco Chronicle, May 5, 2005; Pleasanton Weekly, May 13, 2005). |

However, not all experts agree with those stats. A 21-year Italian study, led by cardiologist Dr. Domenico Corrado at the University of Padua, claimed that U.S. studies are flawed and typically underestimate the frequency of athlete deaths from cardiovascular diseases. Corrado's study put the number at 2.1 per 100,000 -- more than four times the U.S. figure (Journal of the American College of Cardiology, December 2003, Vol. 42:11, pp. 1959-1963).

While experts agree that the number of field fatalities can be reduced via prep screening, they argue about whether athletes should be imaged routinely as part of that screening and how. The consensus tends to favor noninvasive exams, involving as little radiation as possible. Of course, the less expensive the exam, the better.

Tracking an invisible killer

The authors of an extensive report by two working groups of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) concluded that "competitive sports activity enhances by 2.5-fold the risk of sudden death in adolescents and young adults." Furthermore, those "who died suddenly were affected by silent cardiovascular diseases, predominantly consisting of cardiomyopathies, premature coronary artery disease, and congenital coronary anomalies. Therefore, sports activity was not per se a cause of the increased mortality; rather, it acted as a trigger of cardiac arrest" (European Heart Journal, July 2005, Vol. 26:14, pp. 516-524).

|

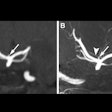

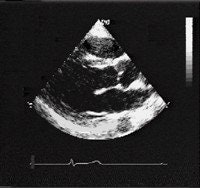

| HCM is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death in young athletes and people younger than 30 years of age. In a normal heart, the heart walls are 11 mm or less in thickness (above and below). |

|

In terms of specific modalities for screening purposes, opinions vary. Dr. Alessandro Biffi and colleagues at the Institute of Sports Science in Rome successfully conducted studies utilizing Holter electrocardiogram, 2D echocardiography, and x-ray to clarify the clinical relevance of ventricular tachyarrhythmias (VAs) in 355 athletes (JACC, August 2002, Vol. 40: 3, pp. 446-452).

But in the consensus statement from the ESC, the authors agreed that echocardiography was "expensive and impractical for screening large populations." They recommended systematic screening with 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG), patient history, and physical exam.

|

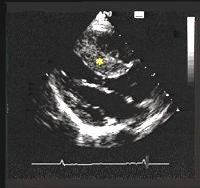

| Patients with HCM have a characteristic thickening of the heart walls that can range from 14-60 mm. Particular thickening of one part of the heart, the interventricular septum, is characteristic of patients with HCM. The thick interventricular septum is marked with an asterisk. Images courtesy of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Program, St. Luke's-Roosevelt Hospital Center, New York City. |

|

According to the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association, "recent studies have shown that a cardiac MRI may be better than an echocardiogram to reliably detect hypertrophy in areas such as the left ventricular anterolateral wall and apex. A cardiac MRI may also be performed to define the precise extent of wall thickening. This information is crucial since the degree of left ventricular wall thickening that a patient has may change therapeutic recommendations."

Proactive measures

Recent high-profile heart-related fatalities of elite professionals have spurred development of formal prescreening programs, especially outside the U.S. The deaths of 28-year-old Russian pairs skater and Olympic gold medalist Sergei Grinkov in 1995 and 24-year-old Hungarian football star Miklos Feher in 1994, for example, have made Europe especially proactive.

Italy now sponsors mandatory preparticipation evaluation for every citizen playing competitive sports -- about 6 million athletes, or 10% of the country's population. The program is administered by physicians specially trained in sports medicine, including sports cardiology, and who work in centers devoted to evaluating athletes.

|

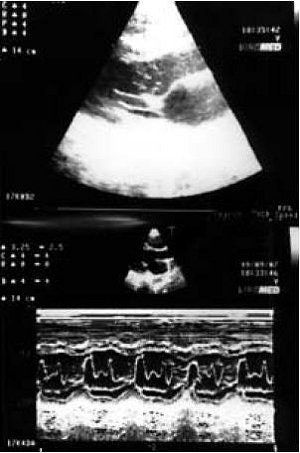

| Diastolic 2D frames showing the elongated anterior mitral chordae tendineae in a 15-year-old boy referred for a routine medical examination. He was a member of a basketball team participating in a local championship. No other structural abnormalities of the mitral valve or signs of obstructive cardiomyopathy were noted. |

Biffi, a cardiologist also with the National Institute of Sports Medicine of Italy and the Italian Olympic Committee in Rome, is one of the program's architects.

"The athletes pay for the screening, which is only 35-40 (euros)," Biffi wrote in an e-mail to AuntMinnie.com. The luckier ones get their tabs picked up by their teams, and those under 18 are covered by the National Health System. Olympic athletes get a free ride, too. "The Italian Olympic Committee pays for them, and they have a more in-depth evaluation at our institute, including Doppler echocardiogram," he stated.

|

| Same patient as above. Systolic 2D frame showing the elongated mitral chordae tendineae prolapsing to the left ventricular outflow tracts (arrows) and M-mode recording (lower photo) showing systolic anterior motion and vibration of the chordae. Although the patient was a competitive athlete, he was only advised for follow-up since there was no resting gradient and the elevation of the left ventricular outflow velocity was mild (< 20 mmHg). Several months later, the boy had the same echocardiographic profile but was in excellent health. Vavouranakis I, Lambrogiannakis E, Meidanis K, Nikolaides G, "Prolapse of abnormal mitral chordae tendineae to the left ventricular outflow tract in normal subject" (Hellenic Journal of Cardiology, 2001;42:561-561). |

Further imaging isn't routine in the protocol, he noted, "although it's requested in case of suspicion. MRI has been very useful for detecting arrhythmogenic dysplasia."

Why the U.S. lags

In their paper, Corrado and colleagues acknowledged that the Italian model for a preparticipation athletic screening program is "difficult to implement," mostly for socioeconomic reasons. But, they wrote, "the hope is that the successful Italian experience will lead progressively to its widespread adoption in the setting of European regulation of the health system."

In fact, the ESC thinks a standard for medical evaluation of competitive athletes is a good thing. It recommends a protocol like Italy's be adopted by the entire European Union.

Meanwhile, the U.S. lags in establishing standardized preparticipation screening programs, which at present differ on a state-by-state -- and even school-by-school -- basis. There are three primary reasons: a lack of national guidelines, the overwhelming cost of healthcare in general, and fear of litigation.

|

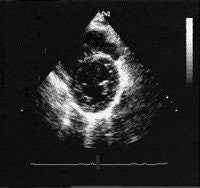

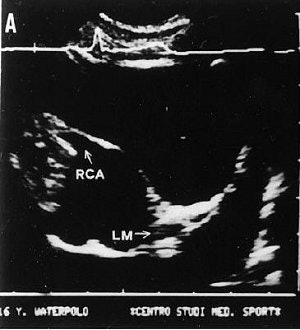

| Seventeen-year-old asymptomatic basketball player. Rest ECG was normal except for rare ventricular escape beats, singled and coupled. Two-dimensional transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) of the left parasternal short-axis aortic view. Panel B (below) clearly shows the right coronary artery (RCA) originating abnormally from the left sinus of the Valsalva, close to the left coronary ostium and the left main (LM), and running around between the aorta and pulmonary artery; for comparison, panel A (above) shows the normal position of coronary ostia in a 16-year-old water polo player. |

|

Dr. Barry Maron, director of the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Center at the Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation in Minnesota, wrote: "It is unlikely that in a country the size of the United States (population 284 million people) ... such an expensive program (like the Italian one) could become a top priority and be created de novo as a federal mandate" (European Heart Journal, March 2005, Vol. 26:5, pp. 428-430).

It is equally unlikely, at a cost of $90 to $200 for a physical exam and an average of $86 for a simple chest x-ray, that American athletes will jump at the chance to finance their own preparticipation screening, as the Italians do.

Additionally, American athletes may not yet be ready to give up their performance-enhancing drugs and anabolic steroids, even though the substances are contributing factors for hypertension and banned by international sports organizations. The widespread use of them isn't something elite athletes and their sponsors wish to see disclosed by compulsory institutional exams.

The specter of legal action is another spoiler. A particularly chilling example occurred in 1990, when basketball player Hank Gathers from Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles collapsed during a nationally televised game and later died due to arrhythmia.

Earlier, a Holter test had shown Gathers had ventricular tachycardia. Team physicians put Gathers on medication, but he cut the dosage back because he didn't like the side effects. His subsequent death resulted in a $32.5 million lawsuit by his estate against Loyola's sports medicine physicians, athletic director, the coach, and a trainer (Gathers v. Loyola Marymount University, Case No. 0759027 Los Angeles Superior Court).

|

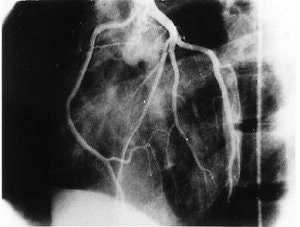

| The same 17-year-old asymptomatic basketball player. Coronary artery angiography in the left oblique anterior view. Selective injection of contrast medium in the left sinus of the Valsalva confirms that the right coronary artery originates from the left sinus just anterior to the left coronary ostium. Zeppilli P, dello Russo A, Santini C, Palmieri V, Natale L, Giordano A, Frustaci A, "In vivo detection of coronary artery anomalies in asymptomatic athletes by echocardiographic screening" (Chest, 1998 Jul;114(1):89-93). |

Seeing a need to intercede, the American Heart Association (AHA) published a set of screening standards in 1996 for identifying athletes at risk for fatal cardiovascular events. The AHA's standards are somewhat like Italy's.

For example, they recommend checking blood pressure and heart sounds of all high school and college athletes every other year to detect coarctation of the aorta and murmurs consistent with left ventricular outflow obstruction. AHA advises an annual personal history be taken to evaluate chest pains, fainting, shortness of breath, or fatigue associated with sports, along with any history of cardiovascular disease in the family.

What the AHA left out of its recommendations is electrocardiography (ECG). The AHA categorizes it as a low-yield exam that is not particularly cost-efficient.

However, Carrado's group argued that "ECG is abnormal in up to 95% of patients with HCM ... and ECG abnormalities have also been documented in the majority of athletes who died from ARVC/D (arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia)." Neither condition is detectable from the blood pressure check and personal history that the AHA considers a sufficient screen.

Carrado went on to note that "the Italian screening modality including 12-lead ECG has 77% greater power for detecting HCM and is expected to result in a corresponding additional number of lives saved, compared with the protocol ... recommended by the AHA."

A good start

Dr. Jeffrey Bytomski, team physician for all sports at Duke University in Durham, NC, said Duke conducts preparticipation screening of all team players that follows the Italian model: history, physical, blood pressure, and imaging as necessary. It's an annual requirement for the athletes, an assembly-line type series of exams in stations set up at Duke's clinic. Anything unusual on an athlete's ECG prompts an immediate referral to the cardiologist for imaging, starting with echocardiography.

Does Duke's system work? So far, so good, Bytomski said in an interview with AuntMinnie.com. "We've had a lot of concussion and dehydration things where athletes were going down on us, but not really any cardiac events. We've been lucky."

"We do have one player who's playing with suspected long QT syndrome," Bytomski added. Suspected long QT syndrome is a disorder of the heart's electrical system. Patients with the syndrome are vulnerable to an arrhythmia in which no blood is pumped out from the heart; the brain is quickly deprived of blood, causing sudden loss of consciousness and death. "She's been seen by at least three cardiologists, who say she's OK," he said.

Dr. Ella Kazerooni, chair of the department of radiology at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and a member of the American Roentgen Ray Society's executive council, told AuntMinnie.com that her university has no formal preparticipation program like Duke's. But she agreed with Biffi and Bytomski that most imaging modalities have limited value in screening athletes for potentially fatal heart conditions.

While cardiac CT might detect an anomalous coronary artery, Kazerooni said, "we do not perform cardiac CT in young, healthy adults. The conditions that young athletes may die from that are cardiac-related are rare, and many are related to abnormalities that coronary CT angiography would not detect."

She noted that the 10 Gy dose from one coronary CT angiogram "is twice the limit radiology techs are allowed to be exposed to annually. For a young athlete, it's not medically acceptable."

When imaging is necessary, for instance if a murmur is detected, Kazerooni said the university typically uses x-ray or echocardiography to image its athletes. "MR would be useful for detecting abnormalities of the heart muscle," she said, "but not for arrhythmias, and it's a very expensive test for a very low yield." In the end, Kazerooni added, "you can't image an arrhythmia."

By Sydney Schuster

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

August 16, 2005

Baseball illustration courtesy of www.classroomclipart.com.

Related Reading

Athlete's heart can be differentiated from dilated cardiomyopathy, March 23, 2005

Cardiovascular screening advised for young athletes, February 3, 2005

Many top cyclists have enlarged hearts, July 15, 2004

Screening seen unlikely to detect at-risk athletes, September 9, 2004

Deconditioning may help athletes with heart condition, September 1, 2004

Copyright © 2005 AuntMinnie.com

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)