According to Dr. Ben Felson, a radiologist at the University of Cincinnati in the 1940s, an "Aunt Minnie" is "a case with radiologic findings so specific and compelling that no realistic differential diagnosis exists." In other words, if it looks like your Aunt Minnie, it probably is.

Radiologists have been relying on that kind of clinical intuition for years. But is intuition always the best way to go when deciding how to screen or treat diseases like breast cancer?

Take the use of MRI with second breast cancers. One would think that with its impressive breast imaging sensitivity -- higher than mammography, ultrasound, or physical examination (some studies put the modality's sensitivity for screening high-risk women at 100%, when combined with mammography) -- using MRI would improve not only outcomes but make treatment plans more appropriate. But the data just aren't there yet, according to Dr. Kimberly Van Zee, attending surgeon, breast service at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and professor of surgery at Weill Medical College of Cornell University, both in New York City.

"I'm a huge MRI fan, and it seems like it's a good thing," Van Zee told AuntMinnie.com. "But looking at it with a cold hard eye, there's no data that prove it helps."

Van Zee presented the state of this particular MRI debate at the 2007 Breast Cancer Symposium in San Francisco, urging her colleagues to consider that even though MRI may seem like a good idea for staging and screening of second breast cancers, the jury is still out. The symposium was sponsored by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

After all, within breast cancer care circles, it used to be believed that mastectomy always resulted in better survival than breast conservation, local recurrence wouldn't affect survival, and high-dose chemotherapy and bone marrow transplant were better than conventional chemotherapy. All these intuitive clinical paradigms have been disproved, Van Zee said.

|

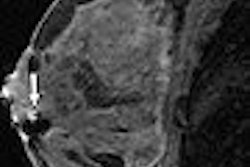

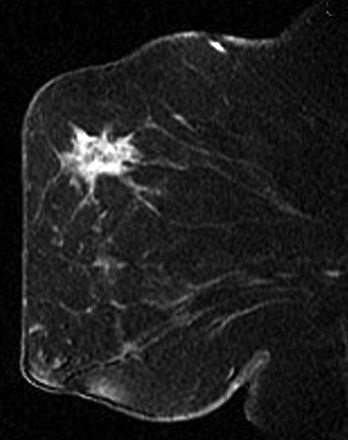

| A 69-year-old woman who presented with palpable left axillary nodes positive for metastatic mammary cancer with no primary cancer identified on mammography or physical examination. Sagittal T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MRI of left breast shows spiculated, irregular, heterogeneously enhancing mass. Biopsy yielded invasive ductal cancer. Bartella L, Liberman L, Morris EA, and Dershaw DD, "Nonpalpable Mammographically Occult Invasive Breast Cancers Detected by MRI" (AJR 2006; 186:865-870). |

Pathologic studies of mastectomy specimens show additional cancer sites in 20% to 63% and multicentric cancer in 20% to 47%; MRIs of the ipsilateral breast diagnosed with invasive breast cancer show additional cancer sites in 6% to 34% and multicentric cancer in 2% to 24%, according to Van Zee. Twenty-year local recurrence rates after breast-conservation therapy with radiation for invasive cancer, without the use of MRI, are about 9% to 14%, and the 10-year local recurrence rate after breast-conservation therapy with radiation and systemic therapy in node-negative patients is about 3.5% to 6.5%. But there is no data on whether the use of MRI lowers local recurrence rates, Van Zee said.

As for long-term survival rates after breast-conservation surgery with radiation versus mastectomy, seven prospective randomized studies show no survival difference; finding hidden disease via MRI couldn't improve survival more than mastectomy, Van Zee said, so whether the modality increases survival rates is unlikely.

Does MRI lead to more appropriate treatment? Possible benefits of staging the ipsilateral breast with MRI include decreasing failed attempts at breast-conservation therapy, decreasing the number of re-excisions, identifying a subset of women who don't need radiation therapy, decreasing the local recurrence rate, and improving survival.

But no prospective studies directly compare either the positive margin rate or mastectomy rate with and without preoperative MRI, Van Zee said, and women who are eligible for breast-conservation therapy have equal survival rates as those who opt for mastectomy. And the possible risks of adding MRI to the breast cancer treatment mix include delays in surgical treatment, morbidity from extra biopsies, undesirable cosmetic results due to wider excisions, and an increase in mastectomies. Add the fact that MRI costs over six times more than mammography per exam, and the case for MRI doesn't look good.

|

|

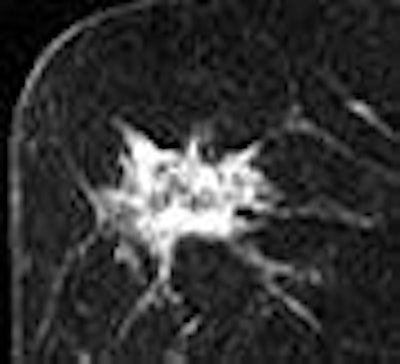

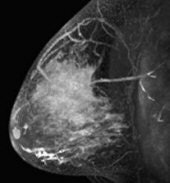

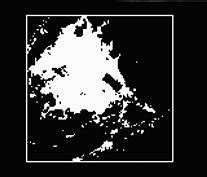

| A 41-year-old patient with invasive ductal carcinoma, grade III, studied while undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment. MRI was performed using contrast-enhanced 3D fast gradient-recalled echo pulse sequence (TR/TE, 8/4.2; flip angle, 20°; 18-cm field-of-view, 2-mm slice thickness, 256 x 192 acquisition matrix). Patient presented with 71 cm3 (6.2-cm diameter) tumor and experienced increase in MRI tumor volume throughout treatment (28% overall increase). At surgery, 8 cm of residual disease and nine involved lymph nodes were identified. Patient experienced disease recurrence eight months after surgery. Maximum intensity projection (left) with corresponding tumor volume segmentation for representative sagittal slice (right) acquired before initiation of chemotherapy. Partridge SC, Gibbs JE, Lu Y, Esserman LJ, Tripathy D, Wolverton DS, Rugo HS, Hwang ES, Ewing CA, and Hylton NM, "MRI Measurements of Breast Tumor Volume Predict Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Recurrence-Free Survival" (AJR 2005; 184:1774-1781). | |

As for using MRI to screen cancer in the contralateral breast, there would seem to be potential benefits in that contralateral breast cancer could be detected along with the ipsilateral cancer, rendering surgery and treatment more effective. But contralateral breast cancer is usually found at an earlier stage than the original case anyway, and is less likely to cause mortality. And possible risks of using MRI for this include false positives and unnecessary biopsies. Even if using MRI to image the contralateral breast prevents some women from choosing partial mastectomy of that breast out of fear, a false positive could lead them to choose an unnecessary surgical procedure, Van Zee said.

What about invasive lobular cancer? MRI better estimates tumor size than mammography alone. But a 2006 study showed no difference in the success rate of breast-conservation therapy or the number of excisions to achieve negative margins with the addition of MRI in 318 women with invasive lobular cancer, compared to the same number of women with invasive ductal cancer. Another recent study showed no difference in local recurrence rates between women with invasive lobular cancer as compared to those with invasive ductal cancer.

MRI may be helpful for women already diagnosed with breast cancer, but good data don't exist and it's possible that MRI could negatively affect patients' treatment. Van Zee called for prospective randomized trials to quantify the risks and benefits of MRI in women with breast cancer, and with this information, clinicians and patients could better weigh the pros and cons of various treatment options.

By Kate Madden Yee

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

September 25, 2007

Related Reading

Fused MRI and PET improve specificity of breast MRI, August 17, 2007

Presence of invasive cancer may cause MR-guided biopsy to miss DCIS, August 16, 2007

MRI beats US for breast screening of at-risk women, but yields more biopsies, August 6, 2007

MRI becoming more efficient in breast cancer detection, May 18, 2007

MRI useful for detecting cancer in contralateral breast, March 28, 2007

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com