It's back to school time in most parts of the U.S. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, more than 30 million youths will partake in organized sports. In many instances, these kids will play hard, practicing as many as five times a week for several hours day, not to mention the actual games.

While these activities are character-building -- encouraging physical coordination and good sportsmanship, for example -- they can also pose a serious health risk beyond scrapes, bruises, and even broken bones. The more young amateur athletes push themselves in the name of spirited competition, the more strain they place on their immature skeletons, which can lead to a condition known as juvenile osteochondritis dissecans (JOCD).

JOCD is a variation on adult osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), which affects the subchondral bone and articular cartilage in joints, resulting in the separation of articular fragments from the bone. JOCD typically affects kids ages 5-15, who still have open growth plates.

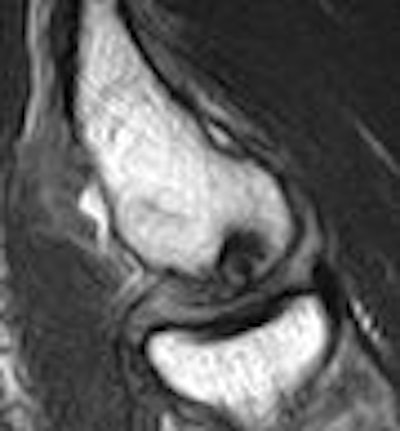

|

| Sagittal MRI of JOCD on 1.5-tesla scanner. Protocol included FSE and T2-weighted imaging (TR/TE 3500/55). Image courtesy of Dr. Nancy Major, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC. |

"We get a lot of referrals for JOCD. The juvenile variety is very different than adults," said Dr. Kathleen Emery, associate professor of radiology and pediatrics at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center. "It is an idiopathic subchondrial lesion of bone that is potentially reversible, but it may go on to delaminate and have associated articulated cartilage infraction and instability."

"The etiology is not clear (but) the overwhelming evidence suggests that it's due to repetitive trauma. We see it very frequently in athletes," added Emery during a talk at the 2007 International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (ISMRM) meeting in Berlin.

"Kids are coming to us more often, because more kids are doing sports," Dr. Nancy Major, a professor of radiology and surgery at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, NC, told AuntMinnie.com. "They come in because they're needing an x-ray for this or an MRI for that, and that's how we're seeing a lot of these JOCD cases."

Which imaging modality to use for diagnosing JOCD is fairly straightforward: Radiographs have some value, but MRI is the best bet. However, what is less certain is the clinical application of imaging information, especially for designing a treatment regimen. The two main options are casting and/or arthroscopy, Emery noted. Figuring out who will heal the best and quickest with either method is a challenge.

"At our institution, (JOCD patients) get casted ... for six weeks. They check them again at six weeks for healing. If it appears they are, they move them on to a brace," she said. "If not, they may take them out of the cast ... and recast them for another six weeks, so we're talking three months already. At that point, they've taken them out of the cast, put them in the brace, and if they are not healing at six months, we deal with them arthroscopically. You can imagine how patients like this kind of therapy. Someone says, 'If I'm not going to heal, let's do the arthroscopy from the start.' And that's the challenge."

AuntMinnie.com polled musculoskeletal experts on what to look for when assessing JOCD and how to avoid misdiagnosing this increasingly common disease process.

"People debate what causes JOCD," said Dr. Douglas Beall, director of radiology services at Clinical Radiology of Oklahoma and associate professor of orthopedics at the University of Oklahoma, both in Oklahoma City. "It's a combination of trauma and probably vascular insufficiency. Then there's a genetic predisposition to OCD; it tends to run in families," he said.

Location, location, location

JOCD is often asymptomatic, but patients may complain of pain, swelling, catching, locking, and giving way. Some patients are unable to fully extend the affected extremity. Presentation varies with age, from inhibition of the ossification front that mimics a defect to advanced lesions manifesting as fracture lines through the subchondral plate and articular cartilage (University of Pennsylvania Orthopaedic Journal, Spring 2001, Vol. 14, pp.25-34).

JOCD generally is estimated at 15-30 cases per 100,000 persons, affecting males 10-20 years old, but is increasing in frequency among females. Eighty-five percent of JOCD cases occur in the medial femoral condyle.

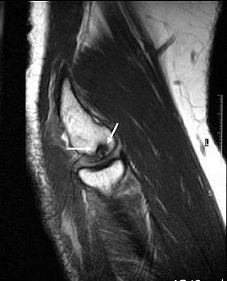

|

| Above and below, OCD of the medial femoral condyle in a female child. Images courtesy of Dr. Douglas Beall. |

|

A 2006 study at Children's Hospital Boston concluded that OCD of the knee "is being seen with increased frequency in pediatric and young adult athletes, and is thought to be, in part, owing to earlier and increasingly competitive sports participation" (American Journal of Sports Medicine, July 2006, Vol. 37:7, pp. 1181-1191).

JOCD that involves "a large portion of the medial femoral condyle of the knee can be tremendously debilitating," Beall said. "We see anything from a casual bruise all the way to a loose osteochondral fragment. Often we'll see OCD that involves only the cartilage, all the way through a little bit of the underlying bone. A lot of times they'll heal; sometimes the cartilage will fissure; sometimes the underlying bone is damaged. Fluid from the joint can get in between the cartilage and the bone," resulting in severe osteochondritis.

Another common location is the ankle (20%), with two different sites of presentation: posteromedial and anterolateral. Anterolateral lesions are true osteochondral fractures that result from trauma (American Family Physician, January 1, 2000, Vol. 61:1, pp. 151-164; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, March 1996, Vol. 78A, pp. 439-456).

Finally, elbow JOCD can affect the humeral capitellum or radial head. Dr. Richard Kijowski and Dr. Arthur De Smet from the Madison-based University of Wisconsin Hospital described elbow JOCD as usually occurring in "adolescent athletes involved in sports activities that place repetitive valgus stress on the elbow joint" (American Journal of Roentgenology, December 2005, Vol. 185:6, pp. 1453-1459).

"Most individuals with capitellar osteochondritis dissecans are young male baseball pitchers or female gymnasts who present with pain, tenderness, and swelling over the lateral aspect of the elbow," they noted.

|

| JOCD of the capitellum. Coronal T2-weighted image (A, above), sagittal T1-weighted image (B, middle) and coronal T1-weighted image with fat saturation (C, below) demonstrate disruption of the articular cartilage (black arrows in images figures A and C) and the crescentic subchondral signal abnormality (white arrows in figures A and C) that is typical of an osteochondritis dissecans lesion. Images courtesy of Dr. Douglas Beall. |

|

|

A rare case of OCD in a shoulder was documented by orthopedist Dr. Philippe Debeer and radiologist Dr. Peter Brys at the University Hospital Pellenberg in Belgium. Their patient was a 17-year-old male whose arm was pulled backward during a fight. X-ray and CT showed a 16-mm defect of the subchondral bone in the central part of the humeral head, which actually turned out to be an older, asymptomatic injury.

Electromyographic studies, however, revealed an elongation injury of the long thoracic nerve, which had caused scapular winging and was clearly post-traumatic (Acta Orthopaedica Belgica, August 2005, Vol. 71:4, pp. 484-488).

Stability and staging

JOCD imaging is usually straightforward. Experts agree that x-ray can detect lesions, but only MRI can show bone and cartilage edema, a necessary exam for assessing stability and staging JOCD. If MRI shows a stage III or IV unstable lesion, arthroscopy can then assess the cartilaginous surface (American Family Physician, January 1, 2000, Vol. 61:1, pp. 151-164).

Using the right modality is especially important when staging JOCD. "The challenge comes in the kids who are not completely ossified yet, and they have a cartilage abnormality," Major said. "You really can't see that on a plain film. CT's OK, but it's not going to give you information about the cartilage. MR resolves all of the structures the best."

"You should see all of this with a standard knee protocol," that includes "a cartilage-sensitive sequence and a fluid-sensitive sequence," she said. "To help determine if the OCD is going to be stable or unstable, we're looking for fluid encircling that fragment."

"MRI is king (for JOCD)," agreed Beall. "If there's a joint effusion, you need the ability to see the fluid surrounding the fragment or going into the fragment. If there's not a whole lot of joint fluid there, which is atypical, we do an MR arthrogram."

Dr. Valmai Cook, a radiologist at Queen Mary's Hospital for Children in Carshalton, U.K., shared her preferred MR protocol for assessing JOCD: "T2 SE sequences with fat suppression can distinguish hyaline cartilage from synovial fluid and can demonstrate a flap or tear in the cartilage, which indicates an unstable lesion that will need surgery. This can usually only be demonstrated if there is an effusion present. Adverse features on MRI are size (> 2 cm), location (weight-bearing surface), narrow growth plates suggesting maturity, and an effusion. The latter is also an adverse clinical feature."

Cook and pediatric surgeon Dr. Mark Churchill conducted a study of 21 knees in 19 JOCD patients and wrote that "after the initial MRI examination, we recommend that stage I, II, and III lesions do not need follow-up MRI unless there is a clinical indication, i.e., ongoing or recurrent knee pain. On follow-up MRI, if the lesion has progressed in stage or extent, but is still not stable, a further MRI in three to six months is advised, depending on clinical symptoms and age of the patient. Stage IV lesions are unstable and require arthroscopy" (Pediatric Radiology, June 2003, Vol. 33:6, pp. 410-417).

Dr. Matthew Marcus, a pediatric radiologist with Hasbro Children's Hospital in Providence, RI, said he prefers x-ray initially, then MRI for staging. "Radiographs of the knee should include tunnel views," he said. "Ankle radiographs should include anteroposterior and mortise views. Three views should be made of the elbow for the capitellum. On CT, findings are comparable to radiography, with more anatomic detail. MRI should include two planes of T1, and probably three planes of fluid-sensitive, fat-suppressed sequences."

Marcus outlined what he looks for in imaging JOCD:

|

| On radiographs |

|

|

|

| On MRI |

|

|

|

Stable JOCD is managed nonoperatively by activity modification or restriction, protected weight bearing, and sometimes casting or bracing. Unstable JOCD lesions are managed surgically by implanting pins or screws, debridement, and subchondral curettage or drilling. Acutrak screws or Kirschner wires are sometimes installed for bigger lesions, Beall noted.

But the jury is still out on the best way to stabilize JOCD lesions. "There's not a great way to fix them. So MRI is very good at aiding in the decision point of whether to do surgery on these kids," he said.

Cook and Churchill reported in their study that all cases with intact cartilage (95%) improved without surgery, despite extensive subchondral bone changes on MRI. Cook told AuntMinnie.com that her hospital has seen "about 100 JOCD cases in about 10 years, and 90% healed spontaneously."

JOCD fragments: Don't miss the big picture

JOCD can easily be underassessed or misdiagnosed, the experts said, leading to serious complications.

In their study of 10 patients, Kijowski and De Smet noted that stable and unstable lesions had similar MRI characteristics on T1-weighted images. All six with stable lesions were surgically confirmed to have intra-articular loose bodies with a mean size of 8 mm.

When researching humeral head OCD, Debeer and Brys found only 11 other reported cases, all in males. Debeer told AuntMinnie.com it could be because JOCD often "may be misdiagnosed as traumatic cartilage lesion."

|

| An 18-year-old man with lateral elbow pain for four months and surgically proven unstable osteochondritis dissecans of capitellum. Anteroposterior radiograph of elbow shows osteochondritis dissecans lesion (arrow) as focal well-defined area of subchondral radiolucency. Kijowski R and De Smet AA, "MRI Findings of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Capitellum with Surgical Correlation" (AJR 2005; 185:1453-1459). |

"We could not detect a traumatic cause in our case," Debeer told AuntMinnie.com. He reported in his study that there were "no signs of instability." "There was a good strength in the rotator cuff muscles. There was no swelling or tenderness, but there was clear winging of the right scapula," he noted.

"There is a well-known variant of delayed ossification of the medial femoral condyle which can be confused with JOCD," added Churchill. "I have seen one case where there was significant delay in ossification bilaterally, and the patient had been treated as JOCD, with very adverse results such as fractures."

Dr. Ilan Elias and colleagues at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia reported that "osteochondral lesions of the talus are relatively common in patients with a history of ankle trauma, but they often are not identified in patients with acute ankle injuries. Moreover, there may be no history of trauma ... in many patients in whom an osteochondral lesion is found" (Foot & Ankle International, March 2006, Vol. 27:3, pp. 157-166).

"(OCD) gets misdiagnosed a lot, probably as arthritis or subchondral edema," Beall said. "Perhaps they won't recognize the fracture. Or maybe the fragment has broken off in the joint, and people will see the overall OCD but not the fragment, especially if it's floating around in the joint" and is not readily identifiable.

|

| Same patient as above. Top, sagittal T1-weighted MR image of elbow shows lesion (arrow) as large area of signal abnormality with low-signal-intensity rim and heterogeneous intermediate signal intensity and low signal intensity centrally. Below, sagittal fat-suppressed T2-weighted fast spin-echo MR image of elbow shows osteochondritis dissecans lesion (arrow) as large area of signal abnormality with high-signal-intensity rim and linear bands of high and low signal intensity centrally. Note marked irregularity of articular cartilage overlying osteochondritis dissecans lesion (arrowhead). |

|

| Kijowski R and De Smet AA, "MRI Findings of Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Capitellum with Surgical Correlation" (AJR 2005; 185:1453-1459). |

Emery stressed that the condition of the articular cartilage is a key to helping orthopedic surgeons determine if their services will be required. "If (the articular cartilage) is intact, that'll give them a chance (at nonsurgical treatment). If the art cart is fractured at the outset, regardless of what the rest looks like, they are more inclined to be aggressive and go on to surgery," she said.

Arguably the most difficult part of JOCD management is patient compliance -- or the lack of it. Convincing kids to sit out a season of their chosen sport is a challenge unto itself. "The younger the patient, the less compliance. Less compliance increases the chances of creating a worse injury," Beall said.

In addition, "long-term follow-up is very difficult in these patients," Emery said. "They are not terribly compliant with bracing. They are anxious to get back into sports. They are frustrated. Their parents are also impatient, as are their coaches -- not to mention that if they are not happy with their treatment, they'll go somewhere else."

By Sydney Schuster

AuntMinnie.com contributing writer

September 4, 2007

Top image © Suprijono Suharjoto.

Related Reading

MRI keeps pace with rapidly evolving musculoskeletal systems of young athletes, May 20, 2007

Skeletal size, muscle mass decreased in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, April 23, 2007

Some female athletes prone to develop leg pain, September 28, 2006

US overcomes x-ray's limits in pediatric ankle fractures, January 23, 2006

Copyright © 2007 AuntMinnie.com