With the help of 3-tesla functional MRI (fMRI), researchers at Purdue University in West Lafayette, IN, have found that some high school football players suffer undiagnosed changes in brain function as a result of repeated hits to the head during games and practices.

While the findings are cause for concern, they also represent a dilemma, because they suggest athletes may suffer a form of injury that does not exhibit the usual clinical signs of a head injury.

"Our task now is to determine if there is a means by which we can detect this impairment, because it does not produce clear dysfunction, in terms of the person having a difficult time talking about things or seeming to have a difficult time doing typical daily interactions," said Thomas Talavage, PhD, associate professor of biomedical engineering and electrical and computer engineering and co-director of the Purdue MRI Facility.

Researchers initially sent invitations to 21 football players at Jefferson High School in Lafayette, IN, asking if they would voluntarily participate in the study, which would include weekly in-season assessments of their cognitive skills. Eleven players agreed to participate, with three of the players returning because they had been diagnosed with a concussion by the team trainer and the team physician. Eight other players were included in the study as control subjects.

ImPACT test

As the season progressed, Talavage and his colleagues observed several players who were consistently impaired, while some of the players exhibited no abnormalities. Their observations were based on the ImPACT test, which was developed by Mark Lovell, PhD, director of the Sports Concussion Program at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.

ImPACT is widely used for postconcussion assessment in professional sports, including the National Hockey League, which mandates its use before players can return to action. The evaluation uses a series of tests and verbal memory tasks that athletes must complete. For example, it assesses a person's ability to recall words or to identify an object or shape shown earlier in the test.

The Purdue researchers gave the high school athletes so-called one-back and two-back memory tests. Participants were shown letters on a screen and were asked to say whether the letter they saw matched the one shown immediately before (one-back) or two letters before (two-back).

To gauge the severity of the hits, researchers also used the HIT system developed by Simbex in Lebanon, NH. The HIT system includes a set of accelerometers that are positioned along the padding inside a helmet to send data to a sideline computer. The computer then registers contact to the head of 14.4 Gs or greater during a game or practice, over the course of the season.

Consistent impairment

In reviewing the data, Talavage and colleagues found that some players "were persistent in impairment, according to ImPACT, and, yet, some of the players weren't. We originally thought we were doing something wrong with the ImPACT test."

So, before the end of the season, the researchers decided to analyze their functional MRI data.

"That's when suddenly -- bam! -- it turned out that all the players who were showing impaired ImPACT performance were also showing significant alterations in their fMRI activation," Talavage added. "That's where fMRI played a huge role, because it ultimately confirmed what we were observing -- that these players were, in fact, cognitively impaired."

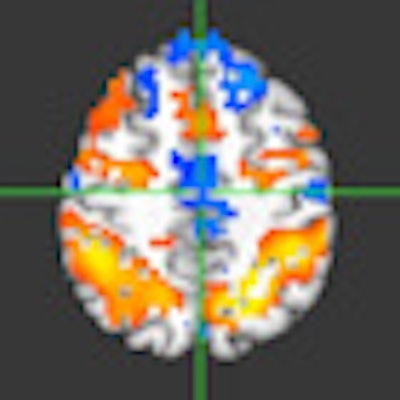

|

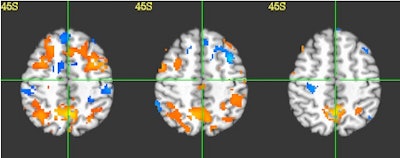

| Functional MRI images of a high school football player with no other impairments or concussions show consistent fMRI activity from preseason (left) to in-season (middle) and postseason (right) images. Orange region denotes greater activity for the two-back test compared to the one-back, compared to the blue region, which shows less activity. All images courtesy of Purdue Acute Neural Injury Consortium. |

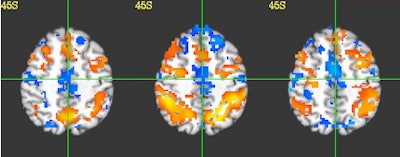

Specifically, the most consistent impairments in changes in the fMRI activation were a decrease in activity in the posterior temporal lobe, which resulted in the athletes having impaired language and memory. Among the four control subjects, the analysis found no consistent changes in their fMRI brain activation.

"The players who are showing this impairment were experiencing an appreciably greater number of hits to the head than the other players who showed no impairment," Talavage said. "In particular, they showed a significantly larger number of blows to the top front of the head and forehead area."

|

| Functional MRI images of a high school football player with functionally observed impairment in the absence of a diagnosed concussion showed significant reductions of fMRI activity in the frontal lobe from preseason (left) to in-season (middle and right). Orange region denotes greater activity for the two-back test compared to the one-back, compared to the blue region, which shows less activity. |

Long-term effects

At this point in the study, which was published in the Journal of Neurotrauma, Talavage and colleagues noted that there is not enough evidence to definitively determine the long-term collective result of repeated hits to the head. They want to extend the research to analyze individuals who develop chronic cognitive impairment but have no history of concussions.

"Clearly, something has happened to their brains, even though they have never registered readily observable clinical symptoms -- at least [symptoms] commensurate with the level of impairment they have later in life," he added.

What is known is that 14 high school football players from last year's study returned for this season and participated in preseason imaging again. As a general rule, their preseason imaging and ImPACT performances were consistent with last year. So, after one year, incidents of repeated hits to the head do not appear to have any significant or notable medium-term effects.

"Now, the question becomes -- like any mechanical system or tissue -- if you keep damaging the brain year after year after year, even if it's capable of rehealing on a short-term basis, eventually, will it experience a longer-term degradation?" Talavage asked. "That is the concern we have, if these players experience this type of deficit every year."

By Wayne Forrest

AuntMinnie.com staff writer

November 22, 2010

Related Reading

Functional MRI may track aberrant pediatric brain development, September 13, 2010

Study offers strategy for managing incidental findings on fMRI, July 6, 2010

Resting fMRI exam may predict stroke and brain injury outcomes, March 30, 2010

fMRI helps find schizophrenia symptoms, January 20, 2009

Functional MRI scans clues to best multitasking times, September 12, 2008

Copyright © 2010 AuntMinnie.com