MRI scans uncovered smaller hippocampal volumes among collegiate football players with a history of concussion or who had played for more years than their teammates, in a study published in the May 14 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The researchers from Oklahoma also found a correlation between playing football and reaction time: The more years an athlete had played, the slower the reaction time.

The hippocampus region of the brain is important because it is involved in multiple cognitive and emotional processes. It is also particularly susceptible to moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Additionally, previous research suggests that mild injury can reduce the volume of the hippocampus and disrupt its function.

However, there is limited information on the neuroanatomical effects of concussion on the hippocampus in young collegiate athletes, wrote lead author Rashmi Singh, PhD, from the Laureate Institute for Brain Research in Tulsa, and colleagues (JAMA, May 14, 2014, Vol. 311:18, pp. 1883-1888).

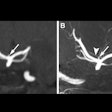

They conducted a cross-sectional study between June 2011 and August 2013 that included 25 players with a history of diagnosed concussion, 25 players with no history of concussion, and 25 nonfootball-playing healthy controls. Whole-body MRI was performed on a 3-tesla scanner (Discovery MR750, GE Healthcare) with a 32-channel head coil to quantify brain volume. Subjects were also given cognitive tests prior to the start of their first football season to assess verbal memory, visual memory, and reaction time.

MR images confirmed that players with and without a history of concussion had smaller hippocampal volumes than the healthy control subjects. The players with a history of concussion had even smaller hippocampal volumes than the athletes with no concussions.

More specifically, hippocampal volume in the left hemisphere was 14.1% smaller for athletes with no history of concussion and 23.8% smaller for athletes with a history of concussion, compared with the controls. Hippocampal volume in the right hemisphere was 16.7% smaller for athletes with no history of concussion and 25.6% smaller for athletes with a history of concussion.

In addition, the number of years spent playing football was inversely associated with both hippocampal volume and reaction time, the researchers found.

While there are some limitations to the study, the findings should "serve as an impetus for future longitudinal research to investigate the neuroanatomical and cognitive changes in young contact-sport athletes," the authors concluded. "The clinical significance of the observed hippocampal size differences is unknown at this time."