Researchers at Johns Hopkins University have developed an MRI technique that homes in on sugar molecules shed by cancerous cells, potentially offering a new way to differentiate malignant from benign lesions, according to a study published online March 27 in Nature Communications.

So far, the technique has only been tested in test tube-grown cells and mice; however, the early results are promising, according to lead author and research associate Xiaolei Song, PhD, and colleagues.

The investigation is the first to use a property integral to cancer cells, rather than an injected dye, to detect the cells, Song said in a statement. This is an advantage because it means clinicians can potentially image the entire tumor, whereas injected dyes only reach part of a tumor -- and are expensive.

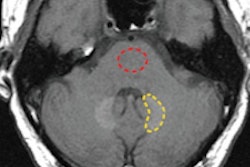

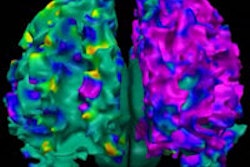

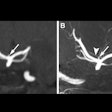

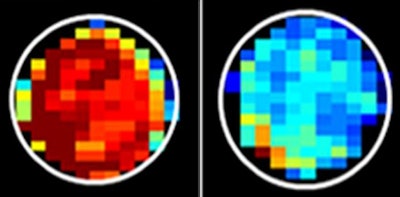

The technique works by visualizing differences in the amount of sugar attached to mucin proteins; normal cells have much more attached sugar than cancerous cells. To detect changes in the MRI signal, Song and colleagues compared MR images of mucins with and without sugars attached. When they then looked for the signal in four types of lab-grown cancer cells, they found markedly lower levels of attached sugars than in the normal cells.

Normal cells (left) have more sugar attached to mucin proteins than do cancerous cells (right). The mucin-attached sugar generated a strong MRI signal (red). Images courtesy of Xiaolei Song, PhD, and Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Normal cells (left) have more sugar attached to mucin proteins than do cancerous cells (right). The mucin-attached sugar generated a strong MRI signal (red). Images courtesy of Xiaolei Song, PhD, and Johns Hopkins Medicine.The researchers noted that more testing is needed to validate the MRI technique for human cancer diagnosis. The next step will be to see if it can distinguish more types of cancerous from benign tumors in live mice.

Ultimately, the technique could be used to detect early-stage cancer, monitor chemotherapy response, and guide biopsies more accurately or perhaps avoid the need for some altogether.