The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on Monday announced that it will investigate the risk of gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) in the wake of several recent studies that found gadolinium deposits in the brains of some patients years after they received contrast-enhanced MRI scans.

At this point, the FDA said it is unknown "whether these gadolinium deposits are harmful or can lead to adverse health effects." Until more details are available, the agency is asking healthcare professionals to consider limiting the use of gadolinium-based contrast to "clinical circumstances in which the additional information provided by the contrast is necessary."

The FDA is also urging users of gadolinium contrast to "reassess the necessity of repetitive GBCA MRIs in established treatment protocols."

In the meantime, the FDA and its National Center for Toxicological Research (NCTR) will try to determine if there is a safety risk. The agency is also collaborating with researchers and industry to understand how gadolinium could remain in the brain so long after administration.

The FDA is "not requiring manufacturers to make changes to the labels of GBCA products," according to its communiqué. Still, it is asking patients, parents, and caregivers to talk to their healthcare providers if they have any questions about the use of gadolinium contrast in an MRI scan, and to report any adverse events.

The issue of whether GBCAs have long-terms adverse effects came to light in late 2013.

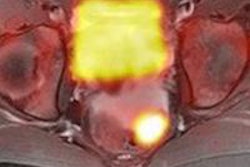

In December of that year, researchers from Teikyo University in Tokyo, led by Dr. Tomonori Kanda, PhD, found a connection between gadolinium-based MRI contrast and abnormalities in two regions of the brain, which could represent a reaction to gadolinium's toxicity. The results suggested the possibility that a toxic component of the contrast agent may remain in the body long after it is injected, even in patients with normal renal function.

In May of this year, Kanda and colleagues confirmed their previous findings that traces of gadolinium contrast remain in the brain years after contrast-enhanced MRI scans. The results raised new questions about the safety of gadolinium-based contrast, such as whether the deposits are harmful.

In another related paper, McDonald et al from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, were unable to explain traces of gadolinium they found in four areas of the brain several years after the administration of MRI contrast.

Finally, Radbruch and colleagues discovered greater signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus of patients who had received gadopentetate dimeglumine (Magnevist, Bayer HealthCare), while there was no such escalation in patients who had received gadoterate meglumine -- despite the fact that a substantially larger dose of contrast was used in the latter group (Radiology, June 2015, Vol. 275:3, pp. 783-791).

The new announcement does not apply to other types of imaging agents, such as radioisotopes or those that are iodine-based, the FDA emphasized.