MRI scans have demonstrated smaller regional brain volumes in people with certain cardiovascular risk factors, which could put them at risk for developing adverse cognitive issues, according to a study published online July 28 in Radiology.

Researchers from the University of Texas (UT) Southwestern Medical Center found that people older than 50 years with a history of alcohol consumption and diabetes had smaller total brain volume, while smoking and obesity were linked to less volume in the posterior cingulate cortex, which aids in memory and emotional and social behavior.

Lower volume in the posterior cingulate was also found in subjects younger than 50 years, suggesting this condition may be an early indication of cognitive issues later in life. In subjects older than 50 years, the most significant volume loss was in the hippocampus and precuneus, which could serve as biomarkers for preclinical cognitive deficits.

"Unfortunately, there is no current efficacious treatment for Alzheimer's disease, so the focus for people with cardiovascular risk factors should be on prevention," lead author Dr. Rajiv Srinivasa, a fourth-year postgraduate in the department of radiology, wrote in an email to AuntMinnie.com. "Our study gives us a greater understanding about the relationship between specific modifiable risk factors and brain health in individuals before and after age 50."

Risk factors and cognition

Previous research has linked cardiovascular risk factors and cognitive decline, but this new study focuses on specific risk factors and examined three main brain regions: the hippocampus, precuneus, and posterior cingulate cortex. Because of each region's connection to memory retrieval, gray-matter volume loss may be a predictor of Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

Dr. Rajiv Srinivasa from UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Dr. Rajiv Srinivasa from UT Southwestern Medical Center."Over the past decade, there has been an increasing body of evidence showing that cardiovascular risk factors impart damage upon the brain and may contribute to cognitive impairment," Srinivasa said. "Our goal was to explore the relationship between specific risk factors in certain key areas of the brain implicated in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease."

This study also follows research by Srinivasa and colleagues published earlier this year. In that study, they found that white-matter hyperintensity and volume measurements of the total brain, hippocampus, cerebrospinal fluid, and gray and white matter were "independently associated with cognitive function and may be important early biomarkers of risk" for cognitive impairment in a young multiracial and multiethnic population (JAMA Neurology, February 2015, Vol. 72:2, pp. 170-175).

While the previous study looked primarily at the cognitive factors associated with changes in brain volume, the current study focuses on the association between vascular risk factors and regional brain volume alterations, Srinivasa said.

"This study expands on the previous findings and provides us with a greater idea about the relationship between specific cardiovascular risk factors and brain health," he added.

Longitudinal comparisons

Srinivasa and colleagues tapped into the large, multiethnic population examined in the Dallas Heart Study (DHS) to gather data on 700 men and 929 women with a mean age of 50 years (± 10.2 years) and no history of stroke. This group underwent laboratory evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors and apolipoprotein E genetic testing between 2000 and 2002 (Radiology, July 28, 2015).

Subjects were excluded if they had a history of stroke, major structural brain defects as seen on MRI, imaging evidence of stroke, and subpar images due to metal artifacts, motion artifacts, or significant levels of noise.

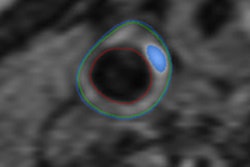

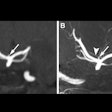

After baseline MR images were obtained, the same participants returned seven years later for follow-up. They underwent MRI brain scans and cognitive assessment with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test to determine possible mild cognitive impairment and the development of preclinical Alzheimer's disease.

The MRI scans were conducted on a 3-tesla scanner (Achieva, Philips Healthcare) using T1-weighted 3D rapid acquisition with gradient-echo imaging.

"MRI was the ideal choice for this study, as it allowed for a quantitative approach by obtaining 3D data, which can be used in volumetric analysis," Srinivasa said. "Further, it allowed for the automated parcellation of the brain into distinct anatomic regions to detect regional differences in brain volume and their association with cardiovascular risk factors."

To help delineate the link between cardiovascular risk factors and smaller regional brain volumes, as well as potential associations with cognitive performance, the researchers divided the participants into two age groups. One group included 805 subjects younger than 50 years old (median age, 42 years; range, 25-49 years). The other group consisted of 824 subjects 50 years or older (median age, 58 years; range, 50-73 years).

"By dividing our cohort into younger and older samples, we were able to investigate how these associations may differ on the basis of age, which expanded on previous studies that identified risk factor profiles in cohorts older than ours," the authors wrote.

For example, the older subjects had a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes and hypertension, along with higher blood pressure, body mass index, cholesterol levels, and fasting blood glucose, compared with the younger group.

"Our sample is unique in that it is from a large-scale population-based study designed to produce population estimates of biologic variables with minimal bias," Srinivasa said. "This allowed us to identify risk factors that contribute to smaller regional brain volumes and identify associations with cognitive function before and after age 50."

Brain volume loss

In comparing overall baseline and follow-up MR images, the researchers found statistically significant smaller volumes in the hippocampus, precuneus, posterior cingulate, and total brain in older participants compared to the younger subjects.

The researchers were also able to link a history of alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity, and diabetes to smaller regional brain volumes in the older group, particularly in the hippocampus, which is critical for memory function.

The younger subjects were not completely in the clear when it came to risk factors. The researchers were able to detect reduced total brain volume due to prior alcohol use, diabetes, and cardiac left ventricular hypertrophy in subjects younger than 50 years, as well as lower brain volume in the posterior cingulate.

Reduced hippocampal volume in the older age group also was associated with poorer performance on the MoCA cognition tests, and there was a correlation between the smaller posterior cingulate and lower test scores among the younger group.

Thus, the authors concluded, reduced volume in the hippocampus and precuneus may be early risk indicators for cognitive decline among individuals older than 50 years, while reduced volume in the posterior cingulate could be a precursor to cognitive issues for those younger than 50.

"The goal of brain volumetry in the clinical setting would be to identify patients at risk for cognitive impairment and follow their regional brain volumes over time," Srinivasa explained. "Subtle changes in regional brain volumes may be detectable early in the course of disease, and this would allow us one method for quantifying the efficacy of lifestyle modifications or other interventions, as they become available, for neurodegenerative disease."

Additional longitudinal studies are needed to determine the long-term consequences that specific cardiovascular risk factors may have on brain health, the researchers noted.

"Further studies are also necessary to determine the impact that lifestyle modifications have on brain health," Srinivasa added. "It is the hope that in the future we will be able to provide patients with useful information about the impact of different risk factors on their individual brain health during routine clinical imaging."