Using cardiac MRI, researchers have found that the mass of the left ventricle changes differently over time in men and women, potentially necessitating more gender-based treatment approaches to maintain heart health, according to a paper published online October 20 in Radiology.

The researchers from several institutions were generally surprised by the gender differences in left ventricular mass seen over the 10-year time frame, but there was no consensus on what might be causing the variations and how the changes could influence a person's risk of an adverse cardiac event.

"The pattern of how the heart changes between men and women over time raises the question about whether optimal therapies should be different for diseases, such as heart failure, that result from these differences," said lead author Dr. John Eng, an associate professor of radiology at Johns Hopkins University. "Right now, if a man or woman develops heart failure as a result of these changes in the shape and size of the heart, they are treated the same."

The mighty left ventricle

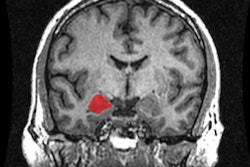

The left ventricle is the main pumping chamber of the heart and has been known to be a predictor of cardiovascular health. Previous research has shown that left ventricular mass can increase or decrease with age, but many of these studies focused on one point in time and young versus older patients, without accounting for lifestyle or other factors.

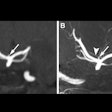

From an imaging standpoint, echocardiography has been the modality of choice to visualize the heart, but it's difficult to delineate the boundary of the wall and the blood inside the heart with this modality.

Dr. John Eng from Johns Hopkins University.

Dr. John Eng from Johns Hopkins University."Cardiac MRI is a 3D imaging technique that can detail where that boundary is," Eng explained to AuntMinnie.com. "It is a more precise way to measure the mass of the heart and the chamber volumes."

Thus, the purpose of the current study was to use cardiac MRI to evaluate age-related left ventricular changes over time in a large cohort of asymptomatic people with no evidence of cardiovascular disease.

MESA data

At the heart of the research is the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), which enrolled more than 6,500 subjects between July 2000 and September 2002 to assess the characteristics and prevalence of cardiovascular disease among asymptomatic men and women (Radiology, October 20, 2015).

Between April 2010 and February 2012, more than 3,500 subjects returned for a fifth follow-up MESA exam. After some participants were excluded due to coronary events, 2,935 individuals were included in this most recent study.

The mean age among this group was 69 ± 9.2 years (range, 54-94 years), and 53% of the participants were women. The median time between baseline cardiac MRI and follow-up scans was 9.4 years.

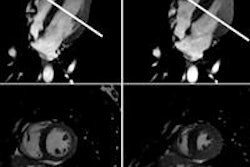

MRI was performed with 1.5-tesla scanners (Magnetom Avanto and Magnetom Espree, Siemens Healthcare; Signa HD, GE Healthcare) using six-channel anterior phased-array torso coils and corresponding posterior coil elements.

The cardiac MRI protocol included the acquisition of one cine horizontal long-axis section for a four-chamber view of the heart, at least 12 cine short-axis sections from the atria to the cardiac apex, and one cine vertical long-axis section for a two-chamber view.

Eng said the entire protocol from start to finish took about 45 minutes, with each pulse sequence lasting three to four minutes.

Left ventricular changes

Cardiac MRI showed that over approximately 10 years, left ventricular volume decreased in both men and women. However, left ventricular mass increased in men by 8 grams per decade (p < 0.001), while it decreased in women by 1.6 grams per decade (p < 0.001).

In other words, men's hearts tended to become heavier and hold less blood, while women's hearts generally became lighter.

What still remains a mystery is why the differences between the genders occur and how they may influence a person's cardiac health.

Eng said the study was not designed to determine the cause of the differences, but rather simply to see how hearts aged.

"We could hypothesize some explanation, but we really don't know what the answer is," he added.

What is known is that additional muscle mass in the men's hearts is not necessarily beneficial, nor is the decrease in left ventricular volume in both genders.

"It is almost as if your heart becomes muscle bound and has a hard time pumping out blood, because it is too thick. So the increase in mass is not considered a good thing," Eng said. "On the other hand, you also want the volume to be maintained, but, as the study shows, volume decreases with age" in both men and women.

Treatment options

The results strongly suggest that treatment approaches for cardiac events such as heart failure or myocardial infarction should be more closely based on the patient's gender, the researchers emphasized.

While Eng and colleagues advocated further research to determine the reasons behind the differences observed, it may be the end of the line for this particular venture, as funding ended with this study.

"I don't know if there will be anything else with this study, but other studies are underway to understand the mechanisms behind these differences," Eng said.

The researchers cited a few limitations of the study, including the fact that follow-up data were obtained for only 60% of subjects who participated in the baseline MRI scans.

"Because of response and survivor bias, the follow-up study population was disproportionately healthier than the baseline population," the authors noted. The original MESA cohort was not intended to be a population of "completely healthy individuals," they added.