There is no need to use gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCAs) with MRI scans to evaluate tumors in pediatric patients, since image quality is essentially the same with no contrast enhancement at all, according to a study published in the January issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

By avoiding the use of gadolinium contrast, these patients could have faster scan times and avoid the risk of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis or the potential threat of accumulating gadolinium chelate deposits in the brain.

And, if gadolinium contrast provides no additional useful information, its absence may help foster the introduction of new MRI contrast agents that aren't based on gadolinium, which could improve diagnostic accuracy over currently available exams, the researchers from Stanford University concluded (JNM, January 2016, Vol. 57:1, pp. 70-77).

Dr. Heike Daldrup-Link from Stanford University.

Dr. Heike Daldrup-Link from Stanford University."Initially, we thought we would find some advantage to contrast-enhanced scans, but we didn't," said study co-author Dr. Heike Daldrup-Link, an associate professor at Stanford and pediatric radiologist at Lucile Packard Children's Hospital. "We found that the diagnostic accuracy was not significantly different from unenhanced sequences, if we look at MRI alone or PET/MRI studies."

Gadolinium concerns

The potential long-term effects of gadolinium-based contrast has been called into question recently due to studies that found gadolinium deposits in the brains of some patients years after they received contrast-enhanced MRI scans. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is investigating the possible safety risk.

"In the past, gadolinium chelates were very well-tolerated, so we didn't look closely at this problem with potential gadolinium deposition in the brain. I think many of us are looking at this now," Daldrup-Link told AuntMinnie.com. "While we are trying to generate better knowledge about the side effects of gadolinium chelates, it is helpful to go back and see whether we need these contrast agents."

The current study enrolled 66 boys and 53 girls with a mean age of 8.1 years (± 6.1 years). The children had benign and malignant tumors and underwent contrast-enhanced MRI between 2005 and 2013 and follow-up imaging for at least 12 months. The majority of cases (103 patients) involved primary tumors, followed by lymph node metastases, multiple bone metastases, and multiple liver metastases.

The researchers also created a subgroup of 36 patients who received FDG-PET scans within three weeks of an MRI and who did not receive treatment between the two imaging tests. This group included 14 male and 22 female patients, ranging in age from 1 to 24 years, with a mean age of 9.9 years. The subjects had 123 tumors confirmed by histopathology and follow-up imaging

MRI scans included 1.5-tesla (Signa HDxt, GE Healthcare) or 3-tesla (Discovery MR750, GE) axial imaging of the abdomen or pelvis using four sequences. The first sequence was unenhanced T2-weighted fast spin-echo (FSE) imaging, followed by unenhanced diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). The third and fourth sequences were T1-weighted 3D spoiled gradient echo liver acquisition with volume acquisition (LAVA) imaging before and after intravenous administration of 0.1 mmol/kg of gadobenate dimeglumine (MultiHance, Bracco Diagnostics).

FDG-PET/CT was performed on an integrated scanner (Biograph 16, Siemens Healthcare or Discovery VCT, GE) after six hours of fasting and 45 to 60 minutes after intravenous administration of FDG (7.77 MBq/kg of body weight). The patients also intravenously received a nonionic contrast agent (Omnipaque 240 or 300, GE) at a rate of 2-3 mL/sec, based on the manufacturer's recommendation for pediatric patients. Whole-body PET and low-dose diagnostic CT scanning time was approximately 25 to 45 minutes.

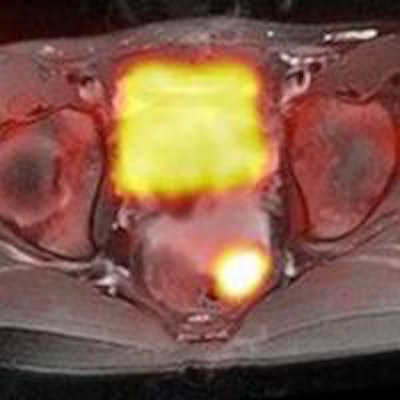

To integrate the anatomic and functional information, the researchers fused PET images with either the unenhanced T2-weighted MRI (to create an unenhanced FDG-PET/MRI) or the enhanced T1-weighted MRI (to create an enhanced FDG-PET/MRI).

"We always try to find the simplest imaging test for our pediatric patients because imaging and any test is very stressful for them," Daldrup-Link said. "We also try to improve our imaging techniques and add new sequences, but we rarely pause and look back to check what we could take out in order to make our imaging tests simpler."

Image comparisons

Three experienced radiologists independently and blindly reviewed the MR images and rated the results based on 14 diagnostic criteria, which included image quality on a four-point scale; primary lesion; tumor as solid, cystic, or both; tumor as homogeneous or inhomogeneous; the details of tumor margins; the presence or absence of necrosis; and final diagnosis.

In the final analyses, the trio of readers rated both enhanced and unenhanced MRI alone as "good to excellent." There was no statistically significant difference between unenhanced MRI, which had an average score of 3.59 (± 0.63), and enhanced MRI, which had a score of 3.63 (± 0.62) (p > 0.05).

There was also no significant difference between unenhanced MRI and enhanced MRI relative to accuracy of any diagnostic criterion.

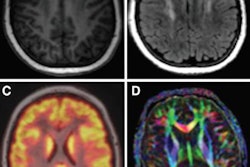

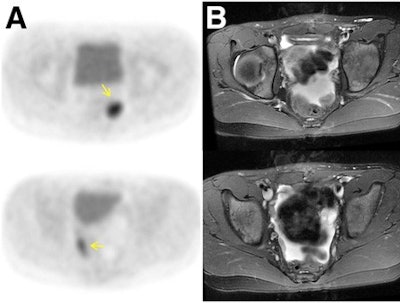

Agreement is achieved with FDG-PET avidity and gadolinium contrast enhancement in a 10-year-old girl after resection of immature teratoma. FDG-PET (A) demonstrates two foci of marked glucose hypermetabolism in left and right lower pelvis (arrows). The T2-weighted MRI (B) shows the foci correspond to small soft-tissue nodules outlined by pelvic fluid, while the T1-weighted MRI (C) after contrast administration shows enhancement of these nodules (arrows) and T2-weighted PET/MRI (D) details the nodules amid pelvic fluid. Images courtesy of JNM.

Agreement is achieved with FDG-PET avidity and gadolinium contrast enhancement in a 10-year-old girl after resection of immature teratoma. FDG-PET (A) demonstrates two foci of marked glucose hypermetabolism in left and right lower pelvis (arrows). The T2-weighted MRI (B) shows the foci correspond to small soft-tissue nodules outlined by pelvic fluid, while the T1-weighted MRI (C) after contrast administration shows enhancement of these nodules (arrows) and T2-weighted PET/MRI (D) details the nodules amid pelvic fluid. Images courtesy of JNM.For example, liver lesions were correctly detected on unenhanced MR images in 84.6% of cases, compared with 85.7% using enhanced MRI. Unenhanced MRI detected bone marrow lesions at a rate of 94.1%, compared with 91% for enhanced MRI. Lymph node lesion detection was identical at 84.9% for both techniques.

Image quality was also rated as "good to excellent" for both the unenhanced and the enhanced FDG-PET/MRI results. Unenhanced images received an average score of 3.6 (± 0.43), compared with an average score of 3.7 (± 0.31) for enhanced images. Again, there was no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) and accuracy did not significantly differ among the diagnostic criteria.

The study's lesion-by-lesion comparison found agreement between FDG avidity and gadolinium contrast enhancement for 106 (86%) of the 123 tumors and discordance in 17 cases (14%).

The patient-by-patient analysis found agreement between FDG avidity and gadolinium contrast enhancement for all tumors in 30 patients, with six discordant cases for at least one tumor. Again, the differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

"We had expected that contrast enhancement would have some advantage on some of these criteria, but when we looked at our data, it turned out that unenhanced sequences were surprisingly good," Daldrup-Link said.

DWI's influence

She credited much of the positive results to the addition of diffusion-weighted imaging MR scans.

"It is very important to differentiate between necrotic and viable tumor tissue, which can be done very well with diffusion-weighted scans," she added.

In fact, DWI-MRI provided information on whether tumors were solid or had cystic or necrotic areas, information that was previously obtained using contrast-enhanced MRI.

DWI was also superior for detecting small peritoneal and serosal metastases, and it offered better contrast between tumors and bowel contents and equivalent images to FDG-PET/CT for patients with lymphoma.

DWI and T2-weighted MRI, however, were limited in characterizing focal liver lesions.

"We therefore suggest that the administration of gadolinium chelates may be necessary only if equivocal liver lesions are identified on unenhanced sequences," the authors wrote.

Scanning time

Daldrup-Link and colleagues are further analyzing the results to determine how much scan time could be reduced by avoiding the use of gadolinium contrast.

Preliminary results show an MRI scan time of 9.8 minutes (± 0.5 minutes) for coronal breath-hold scans (GE) in at least three phases after contrast media injection, plus axial postcontrast scans of the abdomen and/or pelvis.

T2-weighted MRI, diffusion-weighted MRI, and unenhanced T1-weighted imaging (GE) took an average of 31 minutes (± 7.6 minutes), which included time for sequence planning, localizer, and array coil spatial sensitivity encoding (ASSET) calibration.

"So, we could reduce scan time by at least 25% when omitting gadolinium-chelate-enhanced sequences from MRI or PET/MRI scans," Daldrup-Link said.

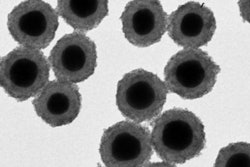

Another potential benefit of the findings is the replacement of gadolinium contrast with other classes of MRI contrast without losing critical information. Ultimately, it could lead to the introduction of agents such as iron oxide nanoparticles, which may improve diagnostic accuracy over currently available exams, she added.

"Our ultimate goal is to provide our patients with the most accurate one-stop imaging test for tumor staging, so they don't have to undergo multiple tests for a certain tumor type to get to a diagnosis," Daldrup-Link said.