CHICAGO - A new study performed among high school football players in North Carolina suggests that just one season spent playing the game causes brain alternations. Findings from the study were presented on Monday at RSNA 2016.

The researchers assessed 24 players who received MRI scans before and after the season, using diffusion-tensor imaging (DTI) and diffusion-kurtosis imaging (DKI) data to measure changes in the brain's white-matter integrity. The players also underwent magnetoencephalography scans to record and analyze the magnetic fields produced by brain waves -- a method of assessing changes in function.

"We saw changes in these young players' brains on both structural and functional imaging after a single season of football," said Elizabeth Moody Davenport, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. "It's important to understand the potential changes occurring in the brain related to youth contact sports."

Those changes occurred without any of the players having received a diagnosis of a concussion during the season, she noted.

The researchers suggested that the results in high school football players could give clues as to how the process begins in which some professional football players develop chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

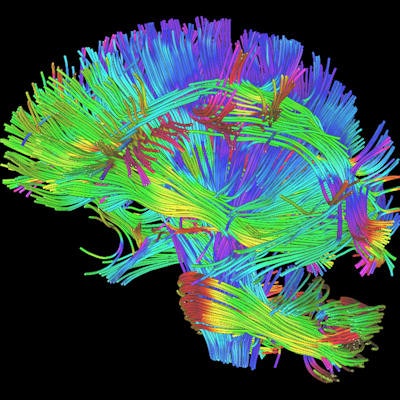

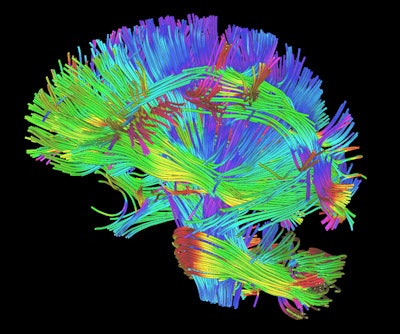

Example of a white-matter rendering from DTI and DKI scans. Image courtesy of RSNA.

Example of a white-matter rendering from DTI and DKI scans. Image courtesy of RSNA.For the study, Davenport and colleagues recruited players to wear a special helmet during their football season. The helmet was fitted with the Head Impact Telemetry System (HITS) during all practices and games. The helmets are lined with six accelerometers that measure the magnitude, location, and direction of impacts. Data from the helmets can be uploaded to a computer for analysis.

The research team calculated the change in imaging metrics between the pre- and postseason imaging exams. The imaging results were then combined with player-specific impact data from the HITS. None of the 24 players were diagnosed with a concussion during the study.

Players with greater head impact exposure had the greatest change in diffusion imaging and MEG metrics, Davenport reported.

The studies are ongoing, with more institutions becoming involved in the project. "Without a larger population that is closely followed in a longitudinal study, it is difficult to know the long-term effects of these changes," she said. "We don't know if the brain's developmental trajectory is altered, or if the off-season time allows for the brain to return to normal."

"While this study provides an intriguing analysis of injury to the structural framework within the brain, as well as functional impairment reflected in abnormal brain waves in high school athletes who sustained varying degrees of head trauma, it demonstrates that these changes occurred in the absence of a clinical diagnosis of concussion," said Dr. Robert Glatter, an emergency room physician and expert in sports-related head injuries at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, who commented on the study. Glatter is also an assistant professor of medicine at Hofstra Northwell School of Medicine.

"This is an important finding since it demonstrates that subconcussive impacts may still result in physical damage to nerve fiber tracts in the white matter of the brain and also generate delta waves, a bellwether of impaired brain function," Glatter told AuntMinnie.com.

He suggested that further research could resolve some of the unanswered questions in the current study.

"What's unclear is whether these changes resolved after a single season of football, and if these physical changes in the brain subsequently led to changes in memory, thinking, and reasoning capabilities, traditionally assessed with specialized neuropsychiatric examinations," he said.

"Long-term analysis -- as well as a larger cohort -- is necessary to study the cognitive function and alterations in brain integrity after a single season of football in this age group to gain a better understanding of the meaning of the observed changes in this small but well-done study."