Researchers from California have developed a way to use diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DWI-MRI) to noninvasively monitor gene expression in tumor cells in living tissue, according to a study published online December 23 in Nature Communications.

So far the method has been used in mice, but if successfully adapted to humans, DWI could help with treatment and monitoring of cancer and other diseases, according to the researchers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

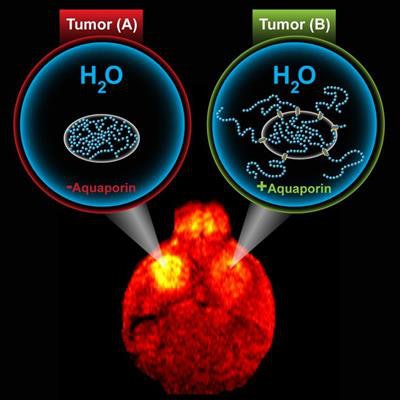

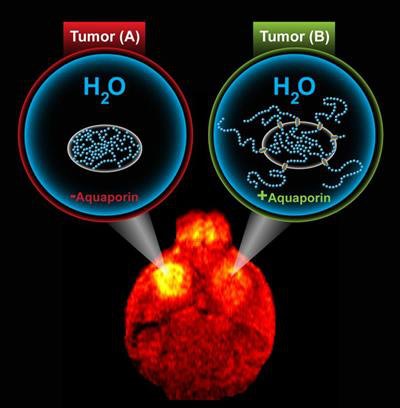

The key is MRI's ability to illuminate hydrogen atoms in the body, which are mostly contained in water molecules and fat, to create images of the brain, muscle, and other tissues. The images then are differentiated based on the local physical and chemical environment of the water molecules.

The researchers hypothesized that if they could link signals from water molecules to the expression of genes of interest, they could change the way the cell looks under MRI, noted study lead co-author Arnab Mukherjee, a postdoctoral scholar in chemical engineering at Caltech.

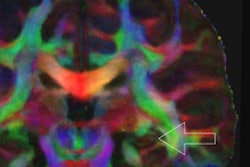

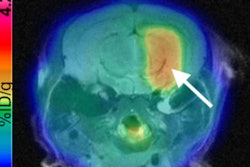

More specifically, they targeted a protein known as aquaporin in the membrane that envelops cells and acts with water molecules. Increasing the number of aquaporins on a given cell made the protein stand out on DWI. The researchers then linked aquaporin to genes of interest to create a "reporter gene," which makes the cell look darker under DWI.

DWI-MRI illustrates aquaporin's effect on tumor cells. Image courtesy of M. Shapiro Laboratory/Caltech.

DWI-MRI illustrates aquaporin's effect on tumor cells. Image courtesy of M. Shapiro Laboratory/Caltech.The overexpression of aquaporin had no negative impact on cells, because it is exclusive to water and allows the molecules to go back and forth across the cell membrane, the authors noted. They added that an effective reporter gene for MRI was the "holy grail" in biomedical imaging, because it would allow cellular function to be observed noninvasively.