Diffusion-tensor MRI (DTI-MRI) is helping researchers at Albert Einstein College of Medicine explore the effects on the human brain of heading a soccer ball. In a new study, they found that players who head the ball more often are more likely to have concussion symptoms.

For several years now, the Einstein Soccer Study has been asking athletes to report their concussion symptoms from a variety of causes, ranging from the seemingly innocuous -- such as heading the ball -- to collisions with other players or a goalpost. By scanning players prior to play, the researchers can get a before-and-after look at the brains of athletes who have had concussions.

"With typical concussion studies, the patient comes to the emergency room after the fact and you really don't know what they looked like beforehand," said Dr. Michael Lipton, PhD, a professor of radiology and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences. "Here, with soccer players, they are providing us with an almost experimental model of how people look before and after a mild head injury."

Better understanding

Dr. Michael Lipton, PhD, from Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Dr. Michael Lipton, PhD, from Albert Einstein College of Medicine.Lipton, who also serves as the director of MRI services at Montefiore Health System, has been involved in concussion research for more than a decade. For the past five years, he and his colleagues have analyzed soccer players to gain a better understanding of the sport's cumulative effects on the brain and any additional risks from an especially large number of repeated impacts.

"Soccer represents a huge exposure to low-level impact to the head, which commonly has been thought not to be clinically significant. On the other hand, we know that repeated impacts to the head can add up to potentially more than the sum of the parts," Lipton told AuntMinnie.com. "If we can understand how the brain reacts to these injuries, then with other venues, such as in the military, other sports, and in the civilian context, we can perhaps better understand the basic biological mechanisms and how treatment and prevention can be affected."

The common wisdom among medical and sports professionals is that soccer concussions and brain injuries are uniformly due to hard impacts, such as accidental player collisions or slamming into a goalpost. Heading is viewed as an uncommon cause of concussion and is considered a subconcussive impact. In other words, it's thought that heading does not lead to any overt signs of concussion or brain injury.

MRI's contribution

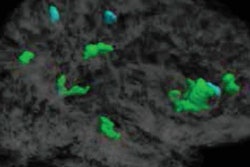

The key method for uncovering soccer's neurological effects is DTI-MRI, which can show areas of abnormally low fractional anisotropy that correlate with nerve fiber damage and cognitive impairment. A 2013 study by Lipton et al found that soccer players who headed the ball six to 12 times per game performed poorly on memory tests and had brain abnormalities similar to those found in patients with traumatic brain injury based on DTI-MRI brain scans.

"MRI potentially allows us to see changes in the brain before there are overt symptoms or brain dysfunction," Lipton explained. "Most importantly, MRI helps us understand the mechanisms of what's going on in the brain, which can be very important when thinking about preventive strategies."

In their current study, published online February 1 in Neurology, the researchers evaluated 222 adult soccer players (175 men, 47 women; age range, 18-55) who completed a total of 470 questionnaires about their soccer activity during two-week periods over the course of nine months in 2013 and 2014.

Players were asked to tally how many times they experienced concussion symptoms, ranging from none to mild, moderate, and severe. Mild symptoms included persistent headache and dizziness, while moderate symptoms included disorientation to the point of having to stop playing at least temporarily. The most severe symptoms included being knocked unconscious.

The median number of headings during a two-week period for all respondents was 40.5; men had a median number of 44 headings, while women had a median of 27. Seventy-eight players (35%) reported one unintentional head impact during a two-week period, while 35 (16%) reported more than one such impact. In addition, 44 players (20%) experienced moderate to very severe concussion symptoms.

What were the consequences of those impacts? In all, 93 (20%) of the 470 questionnaires reported concussion symptoms. Players who headed the most (median of 125 headings in two weeks) were 3.17 times more likely to have central nervous system (CNS) symptoms. Athletes who headed the ball less (median of 28 times in two weeks) were only 1.5 times more likely to have concussion symptoms.

While the moderate to severe concussion symptoms were more strongly connected with unintentional head impacts, the researchers found heading to be an independent risk factor for concussion symptoms. In fact, players who headed the most times were the most susceptible to concussion.

Critical data

"What we do show is that, unsurprisingly, those collisions clearly do cause concussion and concussion-like symptoms, and at a remarkably high rate," Lipton said. "The most interesting and important finding in the study is that heading itself -- independent of those impacts -- accounts for a share of the concussion-related symptoms in soccer players."

Participants in the study have undergone additional MRI scans to delve deeper into the effects of heading. The data are currently being analyzed.

One of the goals of the Einstein Soccer Study is to determine the long-term effects of heading and other head impacts on players. The researchers also hope to determine if certain brain regions are more susceptible to injury.

"What we are finding out here is that there is something going on in the short term, which means that it is very important to look at how that may add up in the longer term," Lipton said. "One of the hints in this data is that, even though heading was an independent source of these brain symptoms, some of which seem to be concussion-related, it is the players who did the most heading who were at risk."

In the meantime, he suggested that soccer players limit how much heading they do over a given period of time.