MRI should be combined with ultrasound to provide additional information to assess fetal brain development in pregnant women who have been exposed to or infected by the Zika virus, according to new research presented this week at the IDWeek 2017 conference in San Diego.

In a prospective study of pregnant women in the U.S. and Colombia, fetal MRI uncovered more extensive damage in developing brains than ultrasound. But by continuing the use of both modalities after birth, clinicians could gain a better understanding of how well an infant's development may or may not progress.

"Ultrasound is a very helpful tool, but MRI can provide further detail that we cannot see on ultrasound," said lead author Dr. Sarah Mulkey, PhD, a fetal/neonatal neurologist at Children's National Health System in Washington, DC. "Our study found that relying on ultrasound alone would have given one mother the false assurance that her fetus' brain was developing normally while the sharper MRI clearly pointed to brain abnormalities."

Zika in the U.S.

As of September 2017, 1,901 women in the U.S. were exposed to the Zika virus at some point during their pregnancies but their infants appeared normal at birth, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, an additional 98 U.S. women gave birth to infants with Zika-related birth defects, and another eight women had pregnancy losses due to Zika infection.

Dr. Sarah Mulkey, PhD, from Children's National Health System.

Dr. Sarah Mulkey, PhD, from Children's National Health System."We don't have a treatment for any of the abnormalities we find with Zika, but if we were to find severe brain abnormalities, that could allow us to provide further information and prognosis to the family," Mulkey told AuntMinnie.com. "For families with babies they know will be born with complex care needs, it gives the [healthcare] team an opportunity to put together a care plan going into the postnatal period."

The researchers at Children's National collaborated with Sabbag Radiologos in Barranquilla, Colombia, to develop a protocol that combines fetal MRI and fetal ultrasound to image pregnant women suspected of being infected with the Zika virus. The approach was available in early 2016 when the first case of a Zika-related pregnancy presented at Children's National.

Also around that time, Mulkey and colleagues designed a research protocol to assess the efficacy of fetal MRI and fetal ultrasound at multiple time points to image Zika-related abnormalities.

To test the combination, the researchers enrolled 46 women in Colombia and two women in the U.S. who were in their first or second trimester of pregnancy and who had been exposed to or were infected by the Zika virus. Their Zika symptoms appeared at a mean 8.4 weeks (± 5.7 weeks) of gestation.

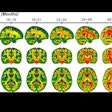

The first fetal MRI and ultrasound scans were performed at 25.1 weeks (± 6.3 weeks) of gestation, with follow-up scans conducted on 36 infants at 31.1 weeks (± 4.2 weeks) of gestation. The infants also underwent similar MRI and ultrasound scans after birth.

Zika's ramifications

Three fetal MRI scans (6%) revealed abnormal findings. One fetus had heterotopias and abnormal cortical indent, while a second had parietal encephalocele and Chiari II malformation. The third had a thin corpus callosum, dysplastic brainstem, temporal cysts, subependymal heterotopias, and generalized cerebral/cerebellar atrophy.

Regarding ultrasound, the corresponding scan of the first fetus was ruled normal. For the second fetus, ultrasound showed the same brain abnormalities as MRI, and for the third, ultrasound showed significant ventriculomegaly and decreasing head circumference from 32 to 36 weeks of gestation.

"MRI allows us to see more subtle, but very significant, brain changes that are not well-appreciated on ultrasound," Mulkey said. "Two of our patients had heterotopia, which did not appear on ultrasound. In one of those abnormal [MRI] cases of heterotopia and an abnormal cortical indentation, that patient's ultrasound was completely normal."

Imaging after birth revealed cysts in the choroid plexus or germinal matrix in nine patients. One infant's ultrasound scan after birth showed brain lesions.

"Some of the findings early on were rather subtle with MRI but became more apparent when we repeated the imaging later," Mulkey said. "Similar with ultrasound, some of these patients had normal measurements early on, but when it was repeated later, we could see that the head growth trajectory had slowed down and the ventricles were getting larger, which is a sign of brain atrophy and the development of microcephaly."

The Zika situation

While there may not be as much public talk about the Zika virus as there was in 2016, it remains a threat in certain areas. In Colombia and Brazil, where infections reached epidemic proportions over the past two years, cases today are "on the downward slope," Mulkey said. However, other countries such as Peru have experienced an increase.

Children's National continues to handle symptomatic patients who have traveled to those endemic areas and returned to the U.S. But the number of Zika-related cases closer to home has fortunately dwindled and is "less of a problem now than it was the year prior," she added.

Still, the researchers plan to continue providing advanced neuroimaging for patients who have been exposed to the Zika virus and have positive test results. Mulkey and colleagues noted how the range of neuroradiographic findings is expanding to offer more information about the potential for long-term or later-developing adverse effects from the Zika virus.

For example, one patient was found to have an ischemic infarct on postnatal MRI that had not been detected during fetal MR imaging. Such an abnormality poses the risk of stroke for the baby. The researchers also discovered cranial nerve enhancement in one child who was imaged after birth.

"A very important question still to answer for these patients is who has been exposed and whether their babies will have normal development after birth," Mulkey said. "We still don't know if these children will develop normally long term or if they will have vision or hearing problems. Much of our focus has to be on understanding some of the long-term outcomes of these apparently normal babies."

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)