Based on brain MR images of people with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), researchers have identified regions of early atrophy that could adversely affect the neurocognitive skills of HIV-positive individuals, according to a meta-analysis published March 28 in Human Brain Mapping.

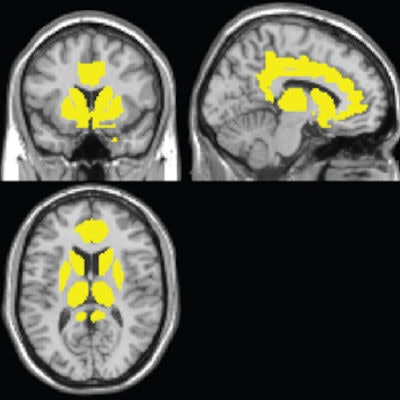

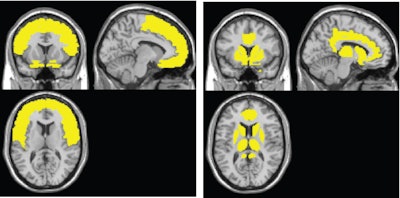

The group used MRI results to develop a two-stage model of the effects of HIV infection. First, the virus leads to atrophy in the frontal lobe, which links the brain's networks and controls executive and cognitive functions, beginning at the time of HIV infection. In contrast, damage to the caudate-striatum region, part of the brain's motor and reward system, becomes more evident when individuals develop clinical HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder symptoms.

"We have long known about neurocognitive impairment resulting from HIV, but this is the first time we have a neural model to relate neurocognitive impairment severity to injury in certain brain structures," said senior author, Xiong Jiang, PhD, director of Georgetown's Cognitive Neuroimaging Laboratory.

Jiang and colleagues have been researching the effects of HIV infection on the brain for several years. Their 2015 study used functional MRI (fMRI) to detect deficits in cognitive function among older HIV-positive individuals, many of whom had normal scores on neuropsychological tests.

For the current study, the researchers used an approach known as colocalization-likelihood estimation to evaluate HIV-related brain atrophy across 25 published studies. The methodology was developed by study co-author Dr. Peter Turkeltaub, PhD, an associate professor of neurology at Georgetown.

The results suggest the use of a two-stage model to evaluate HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder in the context of brain atrophy. The first stage involves the frontal lobe, including the anterior cingulate cortex, while the second phase links HIV with neurocognitive impairment.

Through this model, the researchers determined that the frontal lobe is the most frequently affected brain region in HIV-positive adults, while the neural injury to the caudate-striatum area was consistently linked with neurocognitive impairment.

"There is a strong desire for a neural model of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder severity, which currently is solely defined by neurobehavioral assessments using standard neuropsychological tests," Jiang said. "This model, while highly simplified, might have the potential to help to develop targeted treatment, which in turn might be more effective."

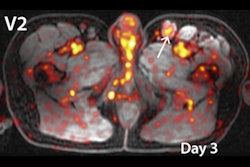

The MR images on the left show gray-matter atrophy commonly seen in a person with HIV. In the images on the right, the atrophy is associated with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, establishing a new profile for the disorder. All images courtesy of Xiong Jiang, PhD, and Georgetown.

The MR images on the left show gray-matter atrophy commonly seen in a person with HIV. In the images on the right, the atrophy is associated with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, establishing a new profile for the disorder. All images courtesy of Xiong Jiang, PhD, and Georgetown.While the researchers acknowledged that the model is not perfect, it does offer "meaningful theoretical and practical implications" for the clinical diagnosis, management, treatment, and future research of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, Jiang said. "It will be of a great interest for future studies to explicitly test the model's predictions," he added.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)