Some called it an attack with a "sonic weapon." Others suggested it was a case of mass hysteria. But what happened to personnel at the U.S. embassy in Havana has mystified medical experts and political pundits. The mystery is only going to deepen with a new study published July 23 in the Journal of the American Medical Association, in which MRI showed structural changes in the brains of affected embassy personnel.

The findings could help explain why so many former embassy personnel continue to suffer from headaches, dizziness, vision problems, tinnitus, and cognitive issues after having been exposed to "uncharacterized directional phenomena" from late 2016 to 2018 in Cuba. What remains a mystery is the cause of the often-severe maladies.

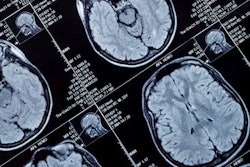

"Advanced brain neuroimaging of a group of U.S. government personnel potentially exposed to directional phenomena while working in Havana, Cuba, showed significant differences in whole-brain white-matter volume, regional gray and white-matter volume, cerebellar tissue microstructural integrity, and functional connectivity in the auditory and visuospatial subnetworks compared with controls," wrote a team of researchers led by Ragini Verma, PhD, professor of radiology at the University of Pennsylvania. "These findings suggest that there may be differences in brain structure involving several different brain regions as well as in some functional brain networks."

Diplomatic controversy

The health problems of personnel at the U.S. embassy in Havana began in the autumn of 2016, when they first noticed strange noises that resembled the sound of insects, according to a February 14, 2018, report by ProPublica. More than 80 individuals underwent evaluation between February and April 2017, with American attachés reporting bouts of headaches, dizziness, vision problems, and tinnitus, according to a study by Swanson et al published in JAMA on February 15, 2018.

That study found "sustained injury to widespread brain networks without an associated history of head trauma" in 21 people who served in Cuba. At least 16 patients (76%) presented with cognitive, balance, visual, and/or auditory dysfunction, as well as sleep impairment and headaches more than three months after exposure to the mysterious sounds.

In addition, Hoffer et al reported in Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology in December 2018 on 35 former embassy employees who presented at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine with intense ear pain, tinnitus, dizziness, and symptoms of cognitive impairment. While the "source of this sound/pressure sensation" was still unknown, the researchers noted that "all of the affected individuals appear to be connected to the diplomatic community in Havana."

Embassy evaluations

In the current study, Verma and colleagues looked to conduct a multimodal approach to investigate possible differences in brain volume, tissue microstructural integrity, and functional connectivity among former embassy personnel patients who now are experiencing the health issues (JAMA, July 23, 2019).

The cohort for the study included 40 patients (mean age, 40.4 years) who were referred for clinical evaluation and treatment following their alleged exposure to "directional phenomena," as Verma and colleagues described the alleged source, while serving in Havana between late 2016 and May 2018. Patients with a history of comorbid neurological conditions were excluded from this study, which included 20 individuals from the research by Swanson et al.

Verma and colleagues also added 48 healthy control subjects (mean age, 37.6 years) and divided them into two groups for comparison purposes. The first set was designed to match the educational background and professional skills and experience of the patients, while the second group consisted of people with a broader spectrum of education and skills.

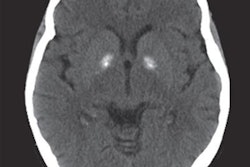

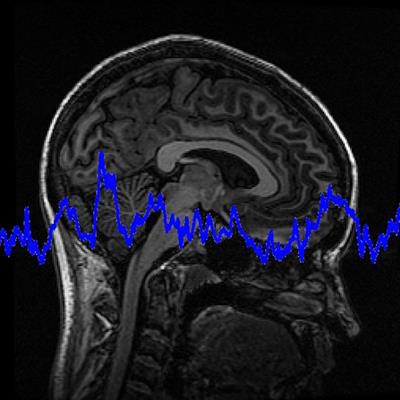

All of the participants underwent advanced neuroimaging on a single 3-tesla scanner (Magnetom Prisma, Siemens Healthineers) a median of 188 days (range, 4-403 days) after initial exposure. The MR imaging protocol included standard 3D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), T1- and T2-weighted imaging, diffusion-weighted MRI, and resting-state functional MRI (fMRI). Total MR image acquisition time was less than one hour.

The T1-weighted images were used for volumetric analysis and to create maps of white matter; gray matter tissue volumes were created as a reference template. In addition, the researchers added multiatlas segmentation to delineate gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid for further statistical analysis of volumetric patterns.

More specifically, the researchers targeted differences in three main outcomes in their comparisons:

- Whole brain and regional brain tissue volume

- Tissue microstructural integrity

- Functional connectivity of auditory, visuospatial, and executive subnetworks

White-matter loss

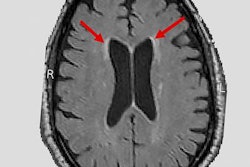

The researchers observed significantly smaller whole-brain white-matter volume among the former U.S. embassy employees compared with healthy controls, as well as significantly smaller frontal, occipital, and parietal lobe white-matter volumes. However, they found no statistically significant difference in whole-brain gray matter volume between the two groups.

Verma and colleagues also discovered a significantly lower mean diffusivity in the inferior vermis of the cerebellum among the U.S. staff, compared with healthy subjects. Finally, through fMRI, they noted significantly lower mean functional connectivity in the auditory and visuospatial subnetworks.

| Comparisons of brain volume and functional connectivity in embassy personnel | |||

| U.S. embassy staff | Healthy controls | p-value* | |

| Whole-brain white-matter volume | 542.22 cm3 | 569.61 cm3 | < 0.001 |

| Diffusivity in the cerebellum | 7.71 × 10-4 mm2/sec | 8.98 × 10-4 mm2/sec | < 0.001 |

| Functional connectivity in the auditory subnetwork | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.003 |

| Functional connectivity in the visuospatial subnetwork | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.002 |

These findings add to the current knowledge on the neurological symptoms and adverse effects experienced by the U.S. embassy staff, added JAMA Senior Editor Dr. Christopher Muth, from the department of neurological sciences at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, in an accompanying editorial.

"However, despite the differences in advanced neuroimaging metrics between patients and controls reported in this study, the clinical relevance of these differences is uncertain, and the exact nature of any potential exposure and the underlying etiology of the patients' symptoms still remain unclear," Muth wrote. "The best way to continue to evaluate these patients is with thorough and objective consideration of rigorously collected scientific evidence."