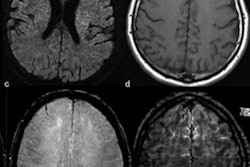

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic are sounding the alarm after discovering that facial recognition software could be used to analyze MRI brain scans and match the data to actual photographs of individuals in research studies. They published their findings online October 24 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The group from Mayo used facial recognition software to analyze reconstructed MRI brain scans and match the images to actual photos of the individuals' faces -- with an 83% success rate. They expressed concern that the discovery could indicate that the privacy of participants in research projects could be violated, a development that could impede the public sharing of research data.

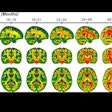

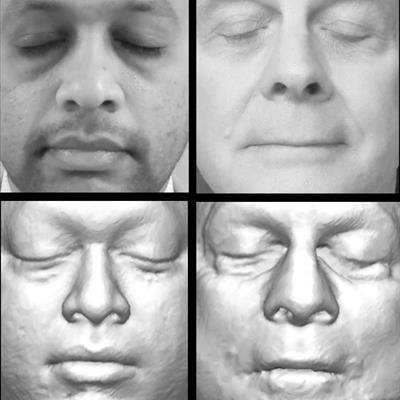

Shown are examples of study participants' photos (top and middle rows) and corresponding facial reconstructions from structural MRI (bottom row). Photos in which the participants' eyes were closed (middle) are shown for visual similarity. Researchers used photos with opened eyes (top) for software-based face recognition. Images courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine.

Shown are examples of study participants' photos (top and middle rows) and corresponding facial reconstructions from structural MRI (bottom row). Photos in which the participants' eyes were closed (middle) are shown for visual similarity. Researchers used photos with opened eyes (top) for software-based face recognition. Images courtesy of the New England Journal of Medicine."This identification would result in an infringement of privacy that could include diagnoses, cognitive scores, genetic data, biomarkers, results of other imaging, and participation in studies or trials," wrote the authors, led by Christopher Schwarz, PhD, a computer scientist in Mayo's Center for Advanced Imaging Research.

Protecting the identities, personal information, and medical records of patients has been a hallmark of healthcare since the inception of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) of 1996. But new technologies -- like facial recognition software -- create privacy problems that were unheard of two decades ago.

"With advances in digital technologies, in this case facial recognition software, it's critical that we continue to revisit the promises that we've made to our patients, particularly promises related to the confidentiality of their medical data," added study co-author Richard Sharp, PhD, the director of the Mayo Clinic Biomedical Ethics Research Program, in a statement. "Much of our work in biomedical ethics focuses on protecting patients from unanticipated harms and this is an excellent illustration of the importance of that work."

To determine the prowess – and threat -- of facial recognition software, Schwarz and colleagues enrolled 84 volunteers between the ages of 34 and 89 years, grouping them according to sex and decade of age. The subjects had undergone brain MRI scans within the previous three months as part of their participation in Mayo Clinic studies.

The researchers then took photographs of the participants' faces from five slightly different angles and used commercial facial recognition software (Microsoft Azure) to build a 3D computer model of the faces from each MRI scan. Their goal was to create 10 2D photograph-like images of each person.

"For each photograph, the software returned a ranked list of the 50 closest matches from the set of 84 MRI-derived faces, with a confidence score for each," the authors explained.

In the end, the software identified the correct MRI scan for 70 volunteers (83%) as the most likely match for their photos. Additionally, the correct MRI scan was among the top five choices for 80 participants (95%). For point of reference, previous studies found that humans had a 40% accuracy rate for the same task.

Given software's ability to readily identify 83% of participants in this study prompted the researchers to suggest that "face recognition provides a possible means of reidentifying research participants from their cranial MRIs. The current standard of removing only metadata in medical images may be insufficient to prevent reidentification of participants in research."

The Mayo Clinic researchers plan to publish a follow-up study to further outline how they could improve existing privacy protection efforts. They also recommended additional research to develop improved deidentification methods for medical imaging that contains facial features.

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=100&q=70&w=100)

.fFmgij6Hin.png?auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&h=167&q=70&w=250)