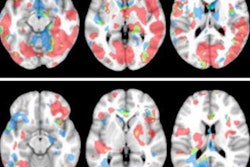

MRI scans have revealed a significant reduction in the brain's white matter among high school and junior high football players after multiple hits to the head over the course of one season, according to a study published in the November issue of the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine.

A team of researchers led by Kim Barber Foss of Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center used diffusion-tensor MR imaging (DTI-MRI) to analyze youth football players at both the high school and junior high levels. They found that DTI-MRI could not confirm conventional thinking that younger players are more susceptible to the damaging effects of repetitive head impacts than their older counterparts.

"Both age groups demonstrated reductions in axial diffusivity from preseason to postseason. These reductions were region-specific in each group," the group wrote (Clin J Sport Med, November 2019, Vol. 29:6, pp. 442-450).

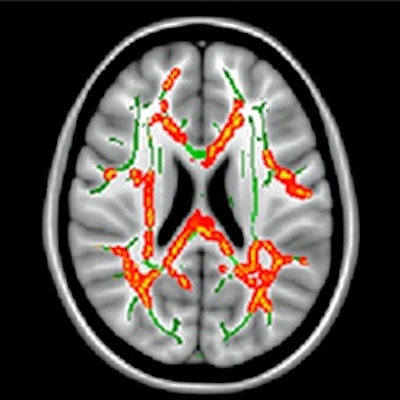

DTI-MRI allows clinicians to visualize the brain's microstructure and white-matter tracts based on the flow of water molecules. A decrease in axial diffusivity can be an indication of fragmented water flow between axons and neurons.

The researchers collected DTI data on 21 high school athletes (mean age, 17.3 ± 0.73 years) and 12 football players in seventh or eighth grade (mean age, 13.1 ± 0.64 years) who underwent 3-tesla MRI scans (Achieva, Philips Healthcare) with a 32-channel head coil before the start of the season and after its conclusion. The number and magnitude of the head impacts greater than a g-force of 10 were recorded for all practices and games on an accelerometer device, which was attached to the same location inside each football helmet.

By the end of the season, the device registered a total of 438 hits (105 in-game and 333 practice exposures) among the youth football players, while the tracker recorded 1,425 athlete exposures (272 game and 1,153 practice exposures) among the high school athletes. The younger group reported one football-related concussion for an incidence rate of 2.28 concussions per 1,000 exposures, while the high school group experienced three concussions for an incidence rate of 2.02 per 1,000 exposures.

A comparison of DTI scans from the preseason to season's end showed reductions in axial diffusivity among both groups in specific brain regions. Interestingly, however, the high school group "demonstrated greater white-matter microstructure changes than the youth football group, as evidenced by more widespread axial diffusivity reduction," which was contrary to the authors' hypothesis, they noted.

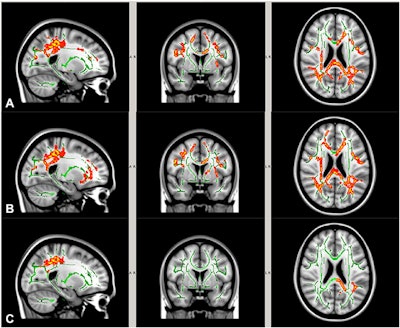

DTI-MR images show white-matter regions with significant preseason to postseason reduction in mean diffusivity (A), axial diffusivity (B), and radial diffusivity (C) among high school football players. Images courtesy of the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine.

DTI-MR images show white-matter regions with significant preseason to postseason reduction in mean diffusivity (A), axial diffusivity (B), and radial diffusivity (C) among high school football players. Images courtesy of the Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine.After adjusting for the number and severity of head impacts, the researchers found the average reduction in axial diffusivity was significantly greater among high school football players than the younger players -- the high school players had approximately a 2.5% reduction in axial diffusivity, compared with a reduction of 0.4% in the younger athletes (p < 0.05).

The group observed significant reductions among the high school athletes in the corpus callosum, anterior and posterior limbs of the internal capsule, corona radiata, and superior longitudinal fasciculus, among other regions. The junior high school footballers showed significant reduction in more limited regions, including the anterior corona radiata, superior corona radiata, and external capsule.

"Although regional differences in involvement may relate to developmental differences between our two studied groups, our results did not confirm recent speculation that younger children are more susceptible to the deleterious effects of repetitive head impacts compared with their older counterparts," Barber Foss and colleagues concluded. "Future studies with larger sample sizes and longitudinal methods consisting of multiple seasons of competitive play are needed to further investigate the age-dependent and region-specific vulnerability of white matter to head impact exposure in contact sports."