Diffusion-tensor MR images (DTI-MRI) have revealed signs of brain damage in the white matter of overweight children, which could be related to several key inflammatory markers, according to a study scheduled for presentation next week at RSNA 2019 in Chicago.

The damage correlated with levels of leptin, a hormone made by fat cells that helps regulate energy levels and levels of stored fat, and insulin levels, which help control blood sugar. Both findings are significant because they directly relate to an obese person's habits and behavior.

"The data reveal a pattern of damage in important regions responsible for control of appetite, emotions, and cognitive functions in obese adolescents, and correlation with some inflammatory markers," wrote the researchers from the University of São Paulo in their abstract.

Obesity in young people has become a serious health issue in the U.S. and around the world. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the number of obese children has tripled in the U.S. since the 1970s, while the World Health Organization estimates the number of overweight or obese infants and young children 5 years old or younger has increased from 32 million around the world in 1990 to approximately 41 million in 2016.

Obesity causes a myriad of adverse effects, including inflammation in the nervous system that could damage key brain regions. One approach to gauge the severity of damage is through DTI, an MRI technique that measures the flow of water molecules in the brain's white matter through fractional anisotropy. Reductions in fractional anisotropy are indications of poor white-matter integrity.

The current study is a follow-up to research the Brazilian team presented at RSNA 2017, in which they reported on the effects of obesity on the brains of children between the ages of 11 and 18. For the new study, the researchers compared DTI results from 3-tesla scans on 59 obese adolescents and 61 healthy adolescents.

Subjects were between the ages of 12 and 16 and were matched for gender, age, sexual development, and education. With DTI, the researchers measured fractional anisotropy values. Lower fractional values are an indication of disrupted flow of water molecules and greater damage in the brain's white matter.

The DTI results showed a reduction of fractional anisotropy values in the obese adolescents in regions located in the corpus callosum, which connects the left and right hemispheres of the brain. The researchers also observed a decrease of fractional anisotropy in the middle orbitofrontal gyrus, which is associated with the control of emotions and the brain's response to rewards. Interestingly, they found no brain regions with an increase in fractional anisotropy in the obese patients.

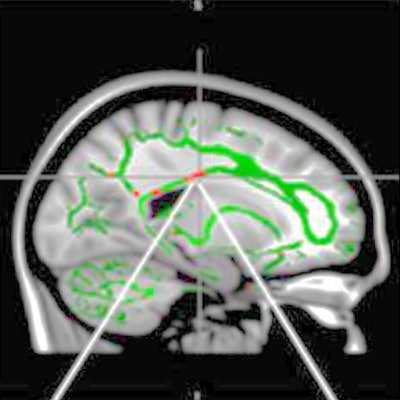

DTI shows reduction in fractional anisotropy in obese patients and control subjects. At the intersection of the alignment vectors, a large cluster of decreased fractional anisotropy is observed in the corpus callosum (red) on the left in obese patients, compared with the control subjects. In addition, there is a reduction in fractional anisotropy and fractional anisotropy skeleton (green) superimposed on the mean fractional anisotropy in sample. Images courtesy of RSNA.

DTI shows reduction in fractional anisotropy in obese patients and control subjects. At the intersection of the alignment vectors, a large cluster of decreased fractional anisotropy is observed in the corpus callosum (red) on the left in obese patients, compared with the control subjects. In addition, there is a reduction in fractional anisotropy and fractional anisotropy skeleton (green) superimposed on the mean fractional anisotropy in sample. Images courtesy of RSNA."Brain changes found in obese adolescents related to important regions responsible for control of appetite, emotions, and cognitive functions," noted study co-author Pamela Bertolazzi, a biomedical scientist and doctoral student from the University of São Paulo in Brazil, in a statement. "Furthermore, we found a positive association with inflammatory markers, which leads us to believe in a process of neuroinflammation besides insulin and leptin resistance."

The researchers recommended additional studies to determine if this inflammation in young people with obesity is a consequence of the structural changes in the brain or from another source.