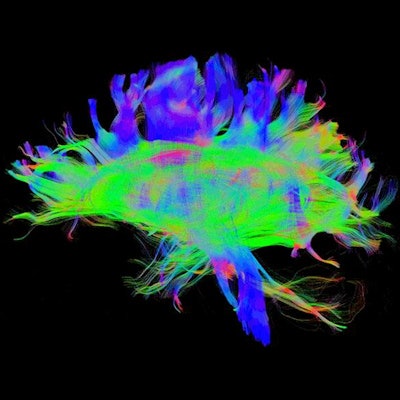

Why does your teenager drive you crazy? A new study used MRI tools such as functional MRI (fMRI) and diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) to shed light on structural pathways in the brain during adolescence -- a time of rapid brain development in humans.

A research group that included investigators from Lifespan Brain Institute at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia took tools from network science to see how white-matter architecture in the brain develops to support neural activity that enables teenagers to develop improved executive function -- behaviors like self-control, decision-making, and higher-level thought.

Researchers investigated the interface between brain structure and function -- called structure-function coupling -- in a group of 727 individuals ages 8 to 23, focusing on how patterns in anatomical connections support synchronized neural activity. Imaging scans were performed using either DWI or fMRI protocols.

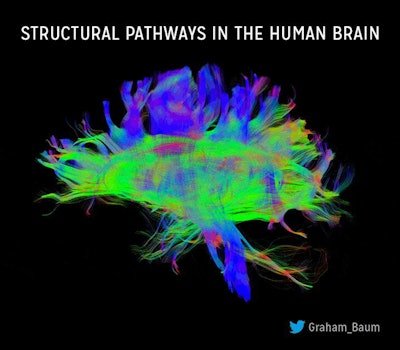

A study examining the relationship between structural and functional brain connectivity in 727 participants ages 8 to 23 used MRI protocols to reveal marked remodeling of structure-function coupling during youth. Image courtesy of Graham Baum.

A study examining the relationship between structural and functional brain connectivity in 727 participants ages 8 to 23 used MRI protocols to reveal marked remodeling of structure-function coupling during youth. Image courtesy of Graham Baum.The investigators made three major discoveries:

- Variability across different brain regions in structure-function coupling was inversely related to the complexity of function a brain area is responsible for, with parts of the brain that are responsible for processing simple sensory tasks showing higher levels of structure-function coupling.

- Structure-function coupling also aligned with patterns of brain expansion over the course of primate evolution that have already been demonstrated in the literature. Previous research on primates has shown that some areas of the brain, like the prefrontal cortex, have expanded greatly during human evolution, while other areas, like the visual system, have not changed much.

- Complex frontal brain regions saw increased structure-function coupling through childhood and adolescence. These areas -- which are responsible for self-control -- tend to have lower levels of coupling at baseline but see prolonged development through adulthood. The researchers also found that in the lateral prefrontal cortex -- which plays a major role in self-control -- higher coupling was associated with better executive function.

"These results suggest that executive functions like impulse control -- which can be particularly challenging for children and adolescents -- rely in part on the prolonged development of structure-function coupling in complex brain areas like the prefrontal cortex," noted lead author Graham Baum, PhD, who was a neuroscience doctoral student at Penn during the research and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University. "This has important implications for understanding how brain circuits become specialized during development to support flexible and appropriate goal-oriented behavior."