MRI scans of a 25-year-old Italian radiologic technologist who contracted COVID-19 and lost her sense of smell suggest the virus may invade the brain through the olfactory pathway and cause dysfunction of sensorineural origin. This finding was published online by JAMA Neurology on May 29.

"To our knowledge, this is the first report of in vivo human brain involvement in a patient with COVID-19 showing a signal alteration compatible with viral brain invasion in a cortical region (i.e., posterior gyrus rectus) that is associated with olfaction," noted Dr. Letterio Politi and colleagues from the department of neuroradiology at the Scientific Institute for Research, Hospitalization, and Health Care (IRCCS) Humanitas Research Center, Milan. "Alternative diagnoses (e.g., status epilepticus, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome-like alterations, other viral infections, and anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis) are unlikely given the clinical context."

The technologist presented with anosmia on March 15. She had been working in the emergency department of the IRCCS Humanitas Research Center and had been in contact with COVID-19 patients. She had a mild dry cough that lasted for one day, followed by persistent severe anosmia and dysgeusia. She did not have a fever. She had no trauma, seizure, or hypoglycemic event.

Three days later, nasal fibroscopic evaluation results were unremarkable, and noncontrast chest and maxillofacial CT results were negative.

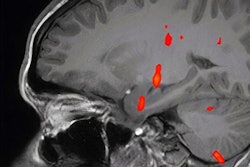

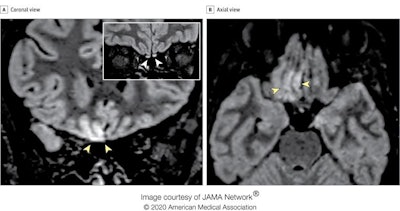

Brain MRI alterations in radiographer with COVID-19 who presenting with anosmia four days from symptom onset. Coronal (A) and axial (B) reformatted 3D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images show cortical hyperintensity in the right gyrus rectus (yellow arrowheads in A and B). In the inset in A, a coronal 2D FLAIR image shows subtle hyperintensity in the bilateral olfactory bulbs (white arrowheads). The cortical hyperintensity is present only in the posterior portion of the right gyrus rectus (B). Accordingly, the cortical hyperintensity of the right gyrus rectus is evident in the more posterior coronal image (A) and not in the anterior coronal one (inset). All images courtesy of JAMA Network.

Brain MRI alterations in radiographer with COVID-19 who presenting with anosmia four days from symptom onset. Coronal (A) and axial (B) reformatted 3D fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images show cortical hyperintensity in the right gyrus rectus (yellow arrowheads in A and B). In the inset in A, a coronal 2D FLAIR image shows subtle hyperintensity in the bilateral olfactory bulbs (white arrowheads). The cortical hyperintensity is present only in the posterior portion of the right gyrus rectus (B). Accordingly, the cortical hyperintensity of the right gyrus rectus is evident in the more posterior coronal image (A) and not in the anterior coronal one (inset). All images courtesy of JAMA Network.The researchers performed two MRI exams on a 1.5-tesla scanner using a 20-channel phased-array head/neck coil. They used no contrast agent and acquired 2D and 3D FLAIR, T2-weighted turbo spin-echo, T1-weighted spin-echo, and high-resolution diffusion-weighted images. Constructive interference in steady-state and susceptibility-weighted imaging sequences were also employed.

"The [technologist] has completely recovered," Politi and co-author Dr. Marco Grimaldi told AuntMinnieEurope.com in a joint email. "She spent 24 days in quarantine, till she had two consecutive RT-PCR (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) swabs negative for SARS-CoV-2. Then she returned to work."

In follow-up MRI performed 28 days later, the signal alteration in the cortex had completely disappeared and the olfactory bulbs were thinner and slightly less hyperintense. The patient had recovered from anosmia. On May 6, a blood sample was positive for the immunoglobulin G antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

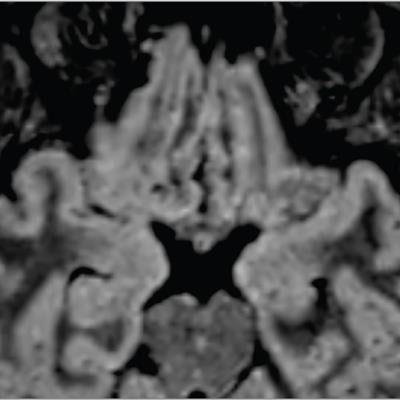

Follow-up MRI in the same patient 28 days from symptom onset. Coronal (A) and axial (B) reformatted 3D FLAIR images show complete resolution of the previously seen signal alteration within the cortex of the right gyrus rectus. In the inset, a coronal 2D FLAIR image shows a slight reduction of the hyperintensity and the thickness of the olfactory bulbs, suggesting a postinfection olfactory loss.

Follow-up MRI in the same patient 28 days from symptom onset. Coronal (A) and axial (B) reformatted 3D FLAIR images show complete resolution of the previously seen signal alteration within the cortex of the right gyrus rectus. In the inset, a coronal 2D FLAIR image shows a slight reduction of the hyperintensity and the thickness of the olfactory bulbs, suggesting a postinfection olfactory loss.The authors found no brain abnormalities in two other patients with COVID-19 who presented with anosmia and who underwent brain MRI 12 and 25 days from symptom onset.

Staff at the Milan institute have so far treated more than 2,300 patients with the virus, and of those, 906 were admitted to the COVID-19 wards or intensive care unit (ICU). A total of 600 beds are dedicated to COVID-positive patients in the wards, and more than 40 ICU beds.

The neuroradiology team has performed MRI exams in more than 20 COVID-19-positive patients. The researchers have other MRI data on patients with more severe disease, but they have recently submitted these cases for publication and cannot disclose the results.

"We will perform follow-up studies on the long-term effect of the CSARS-CoV-2 in the brain. Based on the other MRI scans we have performed, there is evidence that thromboembolisms and vasculitis/endothelin alterations can occur in this disease," Politi and Grimaldi commented.

Free access to the full report is available via the JAMA website.