U.S. Air Force researchers using MRI to assess the brain health of pilots of the U-2 high-altitude reconnaissance and surveillance aircraft have found that age is a bigger factor in negative brain changes than decompression episodes during flight, according to research presented at the virtual RSNA 2020 meeting.

The research is part of an ongoing effort by the U.S. Airforce to track pilot health, presenter Dr. Paul Sherman told session attendees. Sherman is director of aerospace neurology and neuroimaging research at the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine in San Antonio, TX.

"[Any brain health decreases are] concerning [when it comes to] single-seat aircraft operated by a person who needs to make rapid, timely decisions," he said.

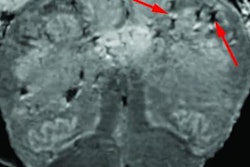

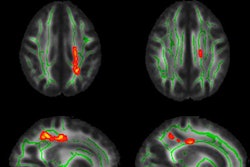

Previous studies have suggested that U-2 pilots experience decreased whole-brain fractional anisotropy (FA) values, increased white-matter hyperintensity (WMH) burden, and other differences in neurocognitive function compared with other military personnel, Sherman said. Higher WMH volume over time is associated with cognitive decline, and FA values within white-matter tracts are useful imaging biomarkers for cognitive function, since they can track white-matter changes in neurological diseases and normal aging before white-matter hyperintensities develop.

Between 2006 and 2010, the incidence of decompression sickness episodes in U-2 pilots increased by 200%, Sherman noted. (Decompression sickness -- "the bends" -- is caused by the dramatic decrease in air pressure surrounding the pilot.)

To address the problem, in 2013, the U.S. Air Force launched the Cabin Altitude Reduction Effort (CARE) initiative, which reduced the altitude equivalent in the cabin from 29,000 feet, roughly equivalent to the height of Mount Everest, to 15,000 feet. However, Sherman and colleagues sought to assess the brain health of U-2 pilots before this program was put into place, considering the question of whether age, flight hour and/or prior history of neurological decompression sickness affected pilots' neurocognitive performance.

The study included MRI and neurocognitive data from before 2013 acquired from 103 pilots between the ages of 26 and 50. The MRI exams included 3D T2-weighted fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and diffusion-tensor MR imaging sequences; the researchers gathered pilots' neurocognitive data through MicroCog, an assessment that identifies early signs of cognitive impairment, and MAB-II, an intelligence test the Air Force uses. The pilots' results were compared with control groups of pilots flying other aircraft and nonpilots.

Age proved to be a significant factor for FA values, Sherman said, with higher ages correlating with lower FA values for white-matter average, corpus callosum body, corona radiata, and thalamic radiation tracts. Length of altitude exposure did not affect FA values, however.

The study also found that exposure hour duration correlated with higher reasoning scores on MicroCog, while increased age matched with increased attention scores but reduced spatial processing scores.

High-altitude flight has its dangers, but it may also contribute to brain health, according to Sherman.

"In this group of U-2 pilots, age was the primary factor for reduced FA values," he said. "[Yet] higher scores in certain cognitive domains of both the MAB-II and MicroCog could be due to the fact that increased flying experience promotes the development of certain visual-spatial skill sets and fosters clinical reasoning abilities."