Functional MRI (fMRI) demonstrated that experiences of racial discrimination can put the parts of the brain that deal with threats into overdrive in a study published January 24 in JAMA Network Open. The research demonstrates the biological effects of racism, according to the authors.

The findings underscore the connection between experiencing racism and ongoing, heightened states of vigilance and stress, noted a group led by E. Kate Webb, PhD, of the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

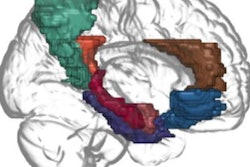

"[Our study shows] an association between racial discrimination and the amygdala and anterior insula, two salience network regions underlying threat-related vigilance," the investigators wrote.

Racial discrimination can manifest as prejudice, unfair treatment, and violence, the group noted. And experiences of racial discrimination are "still pervasive and frequent," particularly for Black Americans, according to the authors.

"Conceptualizing experiences of racial discrimination as a both a form of psychological trauma and as a shared risk factor for psychopathology represents an important shift in the White-centric understanding of the consequences of racism," Webb's group wrote.

The connection between experiencing racial discrimination and poor health has mainly been established through self-reported, rather than neurobiological, data. Webb's group investigated whether there's a link between experiences of racial discrimination and changes in the connectivity in areas of the brain that identify and cope with threat.

The team conducted a study that included 102 Black adults who sustained a traumatic injury between March 2016 and July 2020. Each patient underwent a resting-state fMRI scan, and each was assessed for lifetime exposure to racism and trauma and any symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The researchers then analyzed the association between racial discrimination experienced by study participants and the level of salience network node connectivity (specifically, the amygdala and the thalamus, as well as the insula and the precuneus -- areas of the brain that activate in response to threats and produce "persistent alertness and feeling on guard," the group wrote).

Webb's group found that increased connectivity between the amygdala and the thalamus and between the insula and the precuneus were associated with greater exposure to discrimination, writing that connectivity in these areas represents "neural correlates of vigilance, suggesting a viable mechanism by which racism negatively affects mental health." The results were statistically significant (amygdala and thalamus, p = 0.03; insula and precuneus, p = 0.02).

"Increased amygdala-thalamus connectivity at rest may be reflective of an adaptative

coping strategy to mentally prepare for threats associated with racial discrimination, which are

horrifically persistent for Black U.S. residents living in a White-centric society," the team observed.

The study results are a call to action, according to the investigators.

"While neuroscience research can be used to underscore the biological consequences of racism and help test factors that may buffer against these effects, the overarching goals should be to provide culturally informed treatment to Black Americans with PTSD symptoms and combat racism -- interpersonal and structural -- in U.S. society," they concluded.